Why the West Rules--For Now (15 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

The consequences of global warming were mind-boggling. In two or three centuries around 17,000

BCE

the sea level rose forty feet as the glaciers that had blanketed northern America, Europe, and Asia melted. The area between Turkey and Crimea, where the waves of the Black Sea now roll (

Figure 2.1

), had been a lowlying basin during the Ice Age, but glacial runoff now turned it into the world’s biggest freshwater lake. It was a flood worthy of Noah’s ark,

*

with the waters rising six inches per day at some stages. Every time the sun came up, the lakeshore had advanced another mile. Nothing in modern times begins to compare.

Figure 2.1. The big picture: this chapter’s story seen at the global scale

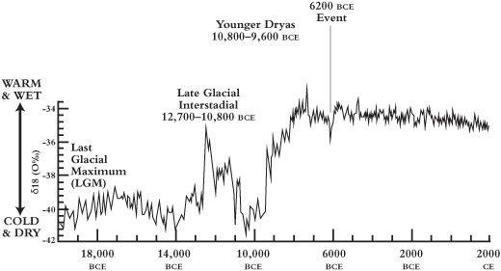

Earth’s changing orbit set off a wild seesaw of warming and cooling, feast and famine.

Figure 2.2

shows how the ratios between two isotopes of oxygen in the Antarctic ice cores mentioned in

Chapter 1

zigzagged back and forth as the climate changed. Only after about 14,000

BCE

, when melting glaciers stopped dumping icy water into the oceans, did the world clearly start taking two steps toward warmth for every one back toward freezing. Around 12,700

BCE

these steps turned into a gallop, and within a single lifespan the globe warmed by about 5°F, bringing it within a degree or two of what we have known in recent times.

Figure 2.2. A story written in ice: the ratio between oxygen isotopes in air bubbles trapped in the Antarctic ice pack, revealing the swings between warm/wet and cold/dry weather across the last twenty thousand years

Medieval Christians liked to think of the universe as a Great Chain of Being, from God down to the humblest earthworm. The rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate—all had their allotted places in a timeless order. We might do better, though, to imagine an anything-but-timeless Great Chain of Energy. Gravitational energy structures the universe. It turned the primeval cosmic soup into hydrogen and helium and then turned these simple elements into stars. Our sun works as a great nuclear reactor converting gravitational into electromagnetic

energy, and plants on Earth photosynthesize a tiny portion of this into chemical energy. Animals then consume plants, metabolizing chemical energy into kinetic energy. The interplay between solar and other planets’ gravities shapes the earth’s orbit, determining how much electromagnetic energy we get, how much chemical energy plants create, and how much kinetic energy animals make from it; and that determines everything else.

Around 12,700

BCE

, Earth leaped up the Great Chain of Energy. More sunlight meant more plants, more animals, and more choices for humans, about how much to eat, how much to work, and how much to reproduce. Every individual and every little band probably combined the options in their own ways, but overall, humans reacted to moving up the Great Chain of Energy in much the same ways as the plants and animals they preyed upon: they reproduced. For every human alive around 18,000

BCE

(maybe half a million) there were a dozen people in 10,000

BCE

.

Just how people experienced global warming depended on where they lived. In the southern hemisphere the great oceans moderated the impact of climate change, but the north saw dramatic contrasts. For foragers in the pre–Black Sea Basin, warming was a disaster, and things were little better for people living on coastal plains. They had enjoyed some of the Ice Age world’s richest pickings, but a warmer world meant higher sea levels. Every year they retreated as waves drowned a little more of their ancestral hunting grounds, until finally everything was lost.

*

Yet for most humans in the northern hemisphere, moving up the Great Chain of Energy was an unalloyed good. People could follow plants and other animals north into regions that were previously too cold to support them, and by 13,000

BCE

(the exact date is disputed) humans had fanned out across America, where no ape-man had trod

before. By 11,500

BCE

people reached the continent’s southern tip, scaled its mountains, and pushed into its rain forests. Mankind had inherited the earth.

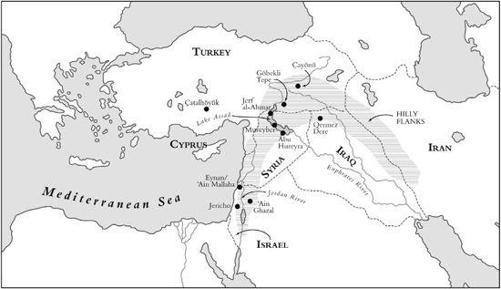

THE GARDEN OF EDEN

The biggest beneficiaries of global warming lived in a band of “Lucky Latitudes” roughly 20–35 degrees north in the Old World and 15 degrees south to 20 degrees north in the New (see

Figure 2.1

). Plants and animals that had clustered in this temperate zone during the Ice Age multiplied wildly after 12,700

BCE

, particularly, it seems, at each end of Asia, where wild cereals—forerunners of barley, wheat, and rye in southwest Asia and of rice and millet in East Asia—evolved big seeds that foragers could boil into mush or grind up and bake into bread. All they needed to do was wait until the plants ripened, shake them, and collect the seeds. Experiments with modern southwest Asian wild grains suggest that a ton of edible seeds could have been extracted from just two and a half acres of plants; each calorie of energy spent on harvesting earned fifty calories of food. It was the golden age of foraging.

In the Ice Age, hunter-gatherers had roamed the land in tiny bands because food was scarce, but their descendants now began changing their ways. Like the largest-brained species of several kinds of animals (whether we are talking about bees, dolphins, parrots, or our closest relatives, apes), humans seem to clump together instinctively. We are sociable.

Maybe big-brained animals got this way because they were smart enough to see that groups have more eyes and ears than individuals and do better at spotting enemies. Or maybe, some evolutionists suggest, living in groups came before big brains, starting what the brain scientist Steven Pinker calls a “

cognitive arms race

” in which those animals that figured out what other animals were thinking—keeping track of friends and enemies, of who shared and who didn’t—outbred those whose brains were not up to the task.

Either way, we have evolved to like one another, and our ancestors chose to exploit Earth’s movement up the Great Chain of Energy by forming bigger permanent groups. By 12,500

BCE

it was no longer unusual to find forty or fifty people living together within the Lucky Latitudes, and some groups passed the hundred mark.

In the Ice Age, people had tended to set up camp, eat what plants and kill what animals they could find, then move on to another location, then another, and another. We still sing about being a wandering man, rambling on, free as a bird, and so on, but when the Great Chain of Energy made settling down a serious possibility, hearth and home clearly spoke to us more strongly. People in China began making pottery (a bad idea if you plan to move base every few weeks) as early as 16,000

BCE

, and in highland Peru hunter-gatherers were building walls and keeping them clean around 11,000

BCE

—pointless behavior for highly mobile people, but perfectly sensible for anyone living in one place for months at a stretch.

The clearest evidence for clumping and settling comes from what archaeologists call the Hilly Flanks, an arc of rolling country curving around the Tigris, Euphrates, and Jordan valleys in southwest Asia. I will spend most of this chapter talking about this region, which saw humanity’s first major movement away from hunter-gatherer lifestyles—and with it, the birth of the West.

The site of ‘Ain Mallaha in modern Israel (

Figure 2.3

; also known as Eynan) provides the best example of what happened. Around 12,500

BCE

, now-nameless people built semisubterranean round houses here, sometimes thirty feet across, using stones for the walls and trimming tree trunks into posts to support roofs. Burned food scraps show that they gathered an astonishing variety of nuts and plants that ripened at different times of year, stored them in plaster-lined waterproof pits, and ground them up on stone mortars. They left the bones of deer, foxes, birds, and (above all) gazelle scattered around the village. Archaeologists love gazelles’ teeth, which have the wonderful property of producing different-colored enamel in summer and winter, making it easy to tell what time of year an animal died. ‘Ain Mallaha has teeth of both colors, which probably means that people lived there year-round. We know of no contemporary sites like this anywhere in the world outside the Hilly Flanks.

Settling down in bigger groups must have changed how people related to one another and the world around them. In the past humans had had to follow the food, moving constantly. They doubtless told stories about each place they stopped: this is the cave where my father died, that is where our son burned down the hut, there is the spring where the spirits speak, and so on. But ‘Ain Mallaha was not just one place in a circuit; for the villagers who lived here, it was

the

place. Here they were born, grew up, and died. Instead of leaving their dead somewhere they might not revisit for years, they now buried them among and even inside their houses, rooting their ancestors in this particular spot. People took care of their houses, rebuilding them over and over again.

Figure 2.3. The beginning of the West: sites in and around the Hily Flanks dliscussed in this chapter

They also started worrying about dirt. Ice Age foragers had been messy people, leaving their campsites littered with food scraps. And why not? By the time maggots moved in and scavengers showed up, the band would be long gone, seeking the next source of food. It was a different story at ‘Ain Mallaha, though. These people were not going anywhere, and had to live with their garbage. The excavators found thousands of rat and mouse bones at ‘Ain Mallaha—animals that had not existed in the forms we know them during the Ice Age. Earlier scavengers had had to fit human refuse into a broader feeding strategy. It was a nice bonus if humans left bones and nuts all over a cave floor, but any proto-rats who tried to rely on this food source would starve to death long before humans came back to replenish it.

Permanent villages changed the rules for rodents. Fragrant, delicious mounds of garbage became available 24/7, and sneaky little rats and mice that could live right under humans’ noses fared better in this new setting than big, aggressive ones that attracted attention. Within a few dozen generations (a century would be plenty of time; mice, after all, breed like mice) rodents in effect genetically modified themselves to cohabit with humans. Sneaky (domestic) vermin replaced their big (wild) ancestors as completely as

Homo sapiens

had replaced Neanderthals.

Domestic rodents repaid the gift of endless garbage by voiding their bowels into stored food and water, accelerating the spread of disease. Humans learned to dislike rats for just this reason; some among us even find mice scary. The scariest scavengers of all, though, were wolves, who also find garbage irresistible. Most humans see drawbacks to having terrifying,

Call of the Wild

–type monsters hanging around, so as with the rodents, it was smaller, less threatening animals that fared best.