Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? (28 page)

Read Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? Online

Authors: David Feldman

W

e don’t know where, when, or who came up with the brilliant idea of topping a peanut butter cookie with fork marks, but that won’t stop us from speculating

why.

Let us consider the possibilities:

1. Watch-Out! Theory

Take us as an example. We love peanut butter. We love cookies. But we don’t like peanut butter cookies. The telltale crisscross has become a warning for us to “stay away” and a convenient way for both sales clerks and customers at bakeries and pastry shops to differentiate between peanut butter cookies and other confections. Peanut allergies can be deadly, so the crisscross is the equivalent of a skull and crossbones to those so afflicted, although we doubt that allergies had anything to do with the origins of the crisscross markings.

2. Just Following Orders Theory

Recipes call for the crisscross markings and most cooks are nothing if not obedient! Jeff A. Zeak, pilot plant manager of the American Institute of Baking, adds:

Some people put the marks on the tops because that was what someone else (Grandma, Grandpa, Mom, or Dad) may have taught them to do and they never thought as to why they were doing it.

We’d guess that this theory best explains why most home bakers adorn their cookies with the crisscross. But how did the practice start in the first place? We place our bet on…

3. The Fork Was In Our Hands Anyway Theory

Read just about any peanut butter cookie recipe and you will see nary a word about spoons. But forks have a way of appearing once, twice, or three times in the directions. Commercial bakers stir cookie batter by machine, but many recipes for home bakers call for the dough to be stirred with a fork rather than a spoon if a mixer isn’t available. Zeak explains why:

Some peanut butter cookie dough recipes can be quite stiff and sometimes almost dry in appearance. By using a fork to mix the dough (mashing the dough between the tines), a greater mixing action is achieved that is very much like the action that is accomplished when using some type of mechanical mixer (with dough being forced, chopped, or smeared through the beaters).

If you look at recipes for chocolate-chip cookies, you’ll see that after the dough has been mixed, you are asked to put a spoonful of batter on the cookie sheet. You needn’t worry about the blob flattening and turning into a nicely-shaped finished product. Peanut butter cookie dough is not as cooperative—if left as a ball, the stiffer and stickier peanut butter dough tends not to flatten out—it’ll look more like a doughnut hole than a cookie. So even if the dough is mixed by hand (a sticky proposition) or a spoon, every peanut butter cookie recipe we’ve seen calls for the baker to flatten the balls with the tines of a fork before putting them in the oven. Different chefs have varying techniques to prevent the batter from sticking to the fork when flattening. Zeak rolls the dough balls in granulated sugar. Others dip the fork in sugar or flour, while still others grease the fork with butter or PAM cooking spray.

Our guess is that the origins of the crisscross markings came when a chef decided that as long as the tines of the fork were required to flatten the dough before baking, why not make an artistic statement at the same time? Some bakers even add a little flair by scoring the cookies

after

they are baked.

Given the Feldman theory of housekeeping, we wouldn’t be shocked if the anonymous but oft-imitated baker who invented the cross marks figured: The fork is already dirty and sticky with peanut butter—why not postpone washing the fork until the last possible moment?

Submitted by Brent Detter of Landisville, Pennsylvania. Thanks also to Cheryl-Anne Smith, via the Internet, and “Barbara,” via the Internet.

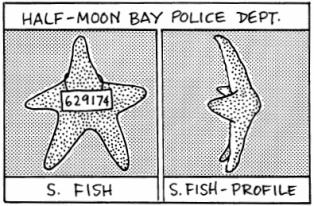

S

tarfish are not fish, and experts tend to get testy if you call them “starfish,” anyway—they are properly known as sea stars, and are classified as Echinodermata (spiny skinned), the same phylum of invertebrates as sea cucumbers and urchins. We tend to think of sea stars as unmoving lumps that lie on the ocean’s floor, when they are actually voracious carnivores, and usually prowling for food.

It’s hard to have a face when you don’t even have a head. Unlike most animals that have a head, sea stars, like all echinoderms, are radially symmetrical with a top side and a bottom side, but no front or back. They feel comfortable moving in any direction, as well they should: they have five—or more—arms and absolutely no notion of forward or backward.

With the naked eye, it isn’t easy to see the sensory organs of a sea star, but they have many of the skills of animals with heads. One thing they don’t have is ears or a sense of hearing. And although they don’t have eyes, they do have eyeholes on each arm that can sense light. Sea stars often lift an arm in order to uncover the eyespot, so they can perceive light or movement in the water. Most sea stars crave the dark, as they escape predators by taking refuge underneath or behind rocks where they cannot be seen.

Seas stars have a groove running along the bottom of each arm that contains hundreds of tiny “tube feet.” These tube feet not only enable sea stars to move, but also are equipped with suction cups, which allow sea stars to grip surfaces with some of the tube feet and propel themselves forward with the others. Each arm contains a single tube foot that is longer than the other feet and does not have a suction cup. When a sea star moves, this special tube foot is able to sense chemicals in the water. Even if sea stars don’t have noses, they do have a highly developed sense of smell, which comes in handy when they are seeking food—their “vision” doesn’t help them much to find prey.

No eyes. No nose. No ears. No heads. Do we come up blank? We are happy to announce that they do have mouths, usually located right in the center of the bottom of the sea star.

We are not so happy to describe how they use these mouths to devour their prey. Bivalves, especially oysters, clams, and mussels, are their favorite food source, but sea stars also feast on coral, fish, and other animals that live near the floor of the sea. While it takes some skill and protective gear for us to pry open an oyster, sea stars have mastered their technique; they wrap their arms around the oyster and use their tube feet to pry apart the oyster shell. Once there is the slightest crack in the shell (one estimate is that it need be open only 1/100 of an inch), the sea star extends its jellylike stomach out of its mouth (yes, its mouth) and inserts the stomach inside the shell of the oyster. The digestive juices of the stomach move into the crack of the shell while the inside-out stomach of the sea star digests its prey. It can take twenty-four hours for a sea star to fully digest a feast of a single oyster, and all of this time the stomach is having an “out of body” experience. Only when the food is fully digested does the sea star’s stomach return to its mouth. If your eating habits were this appalling, you wouldn’t show your face either.

This Imponderable was submitted by two children, but the strange makeup of the sea star has inspired even experts in the field to ponder. While we were researching this question, Echinoderm scholar John Lawrence of the University of South Florida was kind enough to pass along a poem written by the renowned, late biologist from Stanford University, Arthur C. Giese. While Giese’s verse might not achieve poet laureate status, and some of the vocabulary might be obscure (“sessile” refers to animals that live attached to another object its whole life, such as sea sponges), we found it charming. Here’s an excerpt:

Do echinoderms have a face?

The echinoderms are the strangest race

That on our World the Lord did place.

One wonders, do they have a face?

and how kissing between them takes place.

They’re built on a pentameral plan

Figure that out, please, if you can.

Well, their structures are built in multiples of fives

Instead of in pairs as in our lives.

Perhaps because in the evolutionary hassle

The original echinoderms were sessile.

And Gregory writing about the face

Says there is no face in a sessile race.

Their larvae, however, tell a different story

Because bilateralism is there in full glory

The sessile habit was a later phase

That permitted pentamerism to take place.

Please will you now at a sea star look

Or turn to the picture in your invertebrate book

You’ll see not two but five little “eyes”

Looking at you and up to the skies.

Submitted by Jake Itzcowitz of Highland Mills, New York. Thanks also to Maya Itzcowitz of Highland Mills, New York.

W

e have been mildly bemused when buying a pair of dress socks and finding an interloper inside the sock: a folded-up piece of tissue paper. Like the pins and cardboard that must be excised from new dress shirts, we’ve always looked upon the tissue removal as a “cost of doing business” when we forsake athletic socks for dress socks—but their presence never made much sense to us. When a couple of readers wrote in, wondering what the deal with the tissue paper was, we got cracking on solving the mystery.

Like good parents, we love all our Imponderables. But like rotten parents, we love some more than others. Although we weren’t obsessed with this mystery when we started researching it, we became possessed. Right off the bat, we spoke to more than twenty people in the hosiery business and not one of them knew the answer, even folks responsible for the placement of the tissue paper in the socks.

For example, the fifteenth person we spoke to was the director of packaging for a major sock company. To protect her identity, we’ll call her DoP. Here is the relevant excerpt from our conversation:

DF:

I have two questions for you. Why do you put a piece of tissue paper in men’s dress socks? And why in only one sock of the pair?

DoP:

Let me start with the second question first. We put the tissue only in one sock to save money.

[We were now flush with excitement. She was the first person to give us anything but a verbal shrug. Would we finally get the answer we craved?]

DoP:

As for the first part, I don’t know why we put the tissue in.

DF:

Are you the person who is responsible for deciding whether to put a tissue in?

DoP:

Yes.

DF:

You’re the person responsible for putting in the tissue, and you’re worried about the expense, and you don’t know why you do it?

DoP:

[laughing] That’s a good point.

Undaunted, we kept plugging away. One vice president at a maker of store-brand socks suggested we contact the Hosiery Technology Center in Hickory, North Carolina (the epicenter not only of the furniture industry, but hosiery manufacturing in the United States). Surely, we thought, at this august center of hosiery education, someone has done a thesis in the intimate relationship between socks and tissue paper. We received an e-mail from the director of the Hosiery Technology Center, Dan St. Louis, who said that he was stumped, but recommended I speak to a true sock guru:

I would suggest [speaking to] Sam Brookbank, who retired from the hosiery industry with over 60 years in the business. If he doesn’t know, no one does. He is 85 years old and has a mind as sharp as a tack…He is truly a hosiery national treasure. He has forgotten more than I ever will know about hosiery.

We called Sam immediately and posed our Imponderable, and his first response was the same as everyone else we contacted: an immediate chuckle. He paused for a bit and drawled:

In my sixty-plus years in the business, I believe this is the first time this subject has ever come up. I don’t know.

Sam gave us one clue, though. He mentioned that the tissues started popping up in the early 1960s, and definitely were not inserted into socks when he started in the business.

Still, we were crestfallen. After a few midday cocktails and reading a collection of Emily Dickinson’s most depressing poems, we decided that if the Little Engine That Could could, so could we.

In desperation, we contacted our pal Gloria McPike Tamlyn, a marketing consultant for the fashion industry. She started calling her friends and before long we had a whole new list of hosiery honchos to hassle. And then one fateful day, we called a man who became our hero, Jeff Stevenson, the creative director for American Essentials, a company that is best known for manufacturing the socks sold under the Calvin Klein and Michael Kors labels. Like everyone else, Stevenson chuckled when he heard the Imponderable, but then he proceeded to discourse on the matter as if he had been thinking about the subject for hours just before we called. But his thoughts could be summarized tersely:

It’s all about the crinkling. The tissue is only in there for the sound effects it makes.

Days later, we would talk to our other savior, Larry Khazzam, executive vice president of Echo Lake Industries, Ltd., a company that makes Joseph Abboud and fine private label socks. Larry confirmed that the tissue paper has to be crinkly—he compared the appeal to the “Snap, Crackle, and Pop” of Rice Krispies. Indeed, the paper, which comes to the manufacturers in toilet paper–like rolls, is selected precisely for its high crinkliness quotient.

Both Stevenson and Khazzam mentioned that the more senses you can bring into play at the store, the more you can engage consumers. With the tissue paper, you don’t influence the visual appeal of the socks, but you can influence the feel and sound. Both felt that the tissue paper added an element of luxury and refinement. Khazzam added that tissue paper is also used in other luxury garments, such as dress shirts and fine sweaters. Upscale dry cleaners sometimes add some, ostensibly to protect clothing, but mostly to impart a sensation of crispness and luxury to the cleaned clothing.

We confirmed these theories with Richard B. Gualtieri, director of men’s fashion merchandising (and a former men’s furnishings buyer) at New York’s elegant Lord & Taylor department store:

The tissue in the sock is there as part of the esthetic; to add a sense of luxury to the hosiery. It also adds a bit of thickness to the packaging because better men’s hosiery uses finer fabric yarns, which makes them thinner than the less expensive ones.

That little piece of tissue doesn’t come cheaply. According to Khazzam, it costs one to two cents per sock if inserted by machine, as it is in the United States, and three to four cents if done by hand, as it is in many foreign plants. So our director of packaging was right about why the tissue is in only one sock of a pair, and often only in one sock in multipacks of two or more pairs.

As you might have guessed, the choice of which sock is not random. The tissue is always inside the sock on the outside of the package, closest to the consumer, the one that consumers are most likely to fondle before deciding which socks to buy.

There is a little disagreement among our experts about whether the paper provides any protection for the sock at all. Gualtieri notes that socks are delivered to stores in twelve-pair prepacks, and that the paper in the outer sock helps keep the hosiery from getting wrinkled while in the box. Some fine Italian sock makers put tissue paper in the leg and foot area of the sock, which might provide more support.

Khazzam was kind enough to do some digging with his European hosiery sources, and they seem to agree with Sam Brookbank that the practice started in the early 1960s, when tissue paper was put into only the finest socks (gauge 22 and 26 socks, which are very thin). Khazzam writes:

It was started simply as a way of distinguishing the characteristics of the more expensive socks from the rest. What makes a sock more expensive than the next is a function of the desired thickness of the sock, the gauge and the yarn raw material. The reason why the higher gauge socks cost more than the lower gauge is because the initial yarn raw material has to go through more extensive processing; special care must be taken to remove all naps and knots in the raw material; the combing process must be perfect, otherwise the slightest defect would be immediately visible to the consumer.

So the practice of putting the tissue paper inside these socks differentiated the better socks from the others, and became a standard practice. The advent of the insertion machines has made it much easier to put the tissue paper inside the socks, and therefore the practice has become more indiscriminate.

As to the origin of this practice, we can only guess that it began in either Italy or in the U.K., which have the oldest history of knitting the finer-gauge socks. I have gone back three generations with this question, but cannot find the exact answer.

Convinced that we were on the right track, we thought of another common use of tissue paper in an unusual setting. Serious gift wrappers almost always include tissue paper as a component in the final package. When you think about it, if a gift is already encased in a box, which itself is covered by paper wrapping, why is another layer of tissue around the gift necessary? Tissue paper is hardly the most protective covering—surely there is a sock-gift wrap connection. We contacted the king of gift wrap, Hallmark, and we hit pay dirt when Rachel Bolton, a media spokesperson for Hallmark Gold Crown Stores, answered the phone. Just our luck—Rachel has a background in gift wrap and has thought long and hard about the psychology of tissue paper!

Bolton notes that the earliest gift wrapping was probably wallpaper and tissue paper. Our ancestors saved tissue paper used in gift wrapping and treated it as a precious commodity, as paper was expensive and scarce. Nowadays, most folks toss tissue paper after the gift is opened, but some save it, as Hallmark (and other companies) has added more and more design elements to the mix (some have sprinkles, some have a shiny surfaces, some have printed graphics, and tissue paper comes in almost as many colors as Crayolas).

Just as with socks, Bolton believes that tissue paper in gift-wrapped packages is appealing because it adds the element of sound (unprompted by us, she used the word “crinkle” to describe the noise). But the tissue paper also adds a patina of elegance. The extra layer adds suspense to the gift-giving process (some folks even torture the recipient by sealing the tissue paper with a sticker, resulting in mandatory extra crinkling). The honoree feels that the gift is special and more valuable, which is also why you see tissue paper included in some sets of fine stationery and chocolates.

The more Bolton rhapsodized about the process of opening a tissue-paper wrapped gift, the more the image of a striptease occurred to us. If Hallmark sells you as much gift-wrapping product as it would like, the process of opening a gift is not unlike lifting a succession of veils. Bolton believes that adults, unlike some small children, enjoy the slow “tease” of postponing the pleasure of seeing the ultimate gift—they are “into the moment.”

We’re not so sure that sock purchasers are quite as caught up with their tissue paper interaction, but it has consumed

Imponderables

for a few months. How cool is it to research a practice that consumers don’t understand and that most of its practitioners don’t, either? Sometimes we love our job.

Submitted by Donald Montgomery of Atlanta, Georgia. Thanks also to Dan Klinge of Huntington Beach, California; and Carla Fortune of Sweetwater, Texas.