Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? (26 page)

Read Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? Online

Authors: David Feldman

D

o swimming commentators wear Speedos? Do wrestling announcers wear singlets?

Yet male figure-skating announcers look more like they’re going to the prom than to a sporting event. For that matter, the female commentators often look like their prom dates. What’s the deal?

According to Carole Shulman, executive director of the Professional Skaters Guild of America, a clue lies in the lineage of the sport:

Figure skating is an elegant and sophisticated sport. It has been enjoyed by royalty dating back as early as 1660 to the court of Charles II, Duke of Monmouth. Beautiful clothing including long skirts adorned with fur worn by the ladies and waist coats and top hats worn by the gentlemen, can be seen in prints depicting early scenes on the skating pond and mentioned in Scandinavian literature dating back to the first century.

At the turn of the twentieth century and until the 1960s, clothing styles changed but the predominant competition costume for male skaters was the tuxedo. This was the competition era from which Dick Button emerged, first as an Olympic champion and later as a television color commentator. It was natural for Mr. Button to continue the tuxedo from the ice to behind the microphone.

While we weren’t able to contact Mr. Button, in 1999 we spoke to the late Ronnie Robertson, who won the silver medal in the 1956 Olympics. He agreed with Shulman that Button, Sonja Henie, and the other superstars of their era were the successors not only to the elegant European tradition, but the tony early days of U.S. skating, dominated by private skating clubs in Boston, Cleveland, Detroit, and New York. Robertson observed that these clubs

were very exclusive and powerful in the United States Figure Skating Association and it was doctors and lawyers whose families belonged and whose children competed. It was considered a rich man’s sport.

Figure skating has always straddled the line between entertainment and sport. Recently, in a

New York Times

interview with Guy Trebay, 1984 gold medalist and television commentator Scott Hamilton bemoaned some of his fashion atrocities:

“You look at all the beading and the sparkles, and the cringe meter goes to the red,” said Mr. Hamilton, who attributes the current stylistic nadir to the influence of television, which made skating “more about show business and theatrics and less about athleticism” and, oddly, to an expanding fan base for the sport.

The problem is that the sparkly, spangly jump suits that were briefly trendy in the early ’80s look as dated as the disco apparel from the 1970s. Dick Button had the right idea. Scott Hamilton is looking much, much better in his conservative tuxedo.

Submitted by Marian Stoy of Hi-Nella, New Jersey.

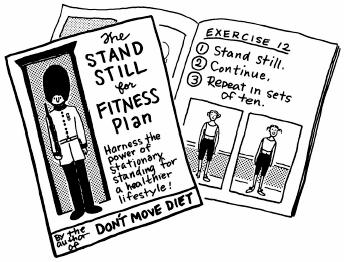

W

e’re quite fond of moving as little as possible. As far as we’re concerned: “La-Z-Boy Recliner,

sí

; exercise,

no

!” But we’ve noticed the same phenomenon as our readers. When forced to stand still for prolonged periods, we feel as antsy as three-year-olds who have drunk too much Pepsi-Cola and had no access to a bathroom.

While there might be some psychological elements at play, the physiological forces are probably dominant. When we stand, gravity pulls the fluid in our body down. The fluid can then pool in the legs and feet, putting pressure on the muscles, and eventually, even pain.

When we move, the contraction of the muscles pushes the fluids back up, and the veins contribute by sending blood back to the heart. Walking increases the circulation not just to your heart, but all over your body, including to not-insignificant organs, such as your brain.

Even sitting for a long time can cause circulation problems. As we discussed in

Why Do Clocks Run Clockwise?

, swelling feet (edema) can be traced to passengers’ lack of movement and sedentary state on airplanes. In extreme circumstances, passengers can suffer from DVT (deep vein thrombosis), when a blood clot develops. That’s why most physicians recommend walking around a bit on long flights, or at least stretching your calves periodically—which might be safer than dodging the service carts in the aisle.

Airplane seats force your legs to be perpendicular to the floor, so it’s easy for fluid to build up, still another reason why we’re antsy on flights. To the extent that antsyness while standing or sitting straight causes us to fidget or move, our discomfort is serving an evolutionary advantage. But the La-Z-Boy devotee has the right idea. By propping up your feet while you sit, you’re not only catching more zzz’s, but preventing edema.

Submitted by Gerald S. Stoller of Spring Valley, New York. Thanks also to Dot Finch of Soddy-Daisy, Tennessee; and Claudette Hegel Comfort and Bob Parker of Minneapolis, Minnesota.

T

he Pilgrims contended with horrendous conditions in freezing New England in the early seventeenth century—blizzards, famine, and epidemics that decimated their population were no picnic. So perhaps we needn’t needle them for picking a time to give thanks for Nature’s harvest when about the only harvestable crop was snow cones.

Actually, the accounts of the first Thanksgiving are remarkably sketchy—all we know is based on two written accounts by colonists. The most detailed account was written by Edward Winslow, three-time governor of the Plymouth colony, who said that the first celebration took three days. The fifty-two surviving colonists invited “some 90” Wampanoag Indians to the feast, who proceeded to thank the Pilgrims by killing five deer, “which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governor, and upon the Captain and others.” Winslow makes clear that the celebration was in honor of the harvest, and that they dined on “fowls” (unspecified in nature, but almost certainly not turkeys). The second account, which corroborates most of the information in Winslow’s letter, was written by William Bradford (another Plymouth governor), in a book written twenty years later.

Significantly, neither version referred to the harvest celebration as “Thanksgiving” nor indicated the exact date of the festivities. Most likely, the colonists were heartened by their first bountiful crop, and were inspired by traditional English harvest celebrations. If they thought they were starting an important new holiday, they probably would have repeated the revelry the following year—but they did not. Historians at the Plimouth Plantation believe that the three feast days occurred sometime between September 21 and November 11, 1621.

Chances are, the Pilgrims would have been dismayed by the appropriation of the word “Thanksgiving” to describe their three-day party. To the Pilgrims, thanksgivings were days of solemn prayer and contemplation in church, not festivities featuring eating, singing, dancing, games, and merriment.

Over the next couple centuries, a series of proclamations declared official holidays of Thanksgiving. The first attempt to make a holiday of gratitude was in 1676, when the Massachusetts council proclaimed the balmy date of June 29 as a day of Thanksgiving, although obviously not a harvest festival. The first time all thirteen of the original colonies celebrated on the same date was in 1777, to commemorate the victory over the British forces in Saratoga. George Washington proclaimed a national day of thanksgiving; but soon Thomas Jefferson yanked it away. Up until the Civil War, Thanksgiving celebrated different things at different dates in different places.

Before the Civil War, most communities celebrated local harvest festivals. The dates of the festival tended not to be fixed, as harvest dates in the same locale varied from year to year (farmers didn’t feel like celebrating before the crops had been picked). Most local Thanksgivings were held between mid-September and mid-October, just after crops had been harvested.

You’d think that the middle of the Civil War wouldn’t be an opportune time to launch a new holiday, but then it would be hard to conceive of someone as obsessed with the subject as Sarah Josepha Hale, a novelist turned media star, who became the editor of the influential women’s magazine,

Godey’s Lady’s Book.

Hale used her soapbox to create a mythology about the first Thanksgiving that lives on today—that the Pilgrims supped on plump, stuffed turkeys, and polished off the meal with pumpkin pie. But Hale didn’t stop with Martha Stewartish features about Pilgrim cuisine. She used her editorial page to lobby for a national Thanksgiving holiday, and privately lobbied politicians and other prominent people.

The American Civil War lasted from 1861 to 1865. Why did Abraham Lincoln declare Thanksgiving a national holiday in the

middle

of the war, 1863, when he must have had much more pressing matters on his mind? Although Hale was relentless in her pressure, she had been railing at presidents for decades without success.

May we bring up the dreaded word,

politics

? After many victories, the Union encountered a series of reversals in 1863. Robert E. Lee’s troops were wounded but not routed at Gettysburg, and then Major General William Rosecrans’s troops were crushed by Confederate forces at Chickamauga Creek in Tennessee. More than 35,000 Union soldiers were lost at Chickamauga, and Lincoln referred to Rosecrans as “confused and stunned like a duck hit on the head.”

While spirits were low and casualties were high, Lincoln had something else to worry about—reelection. In his Thanksgiving Proclamation, Lincoln alluded to the war as being “of unequaled magnitude and severity,” but parts of it read like a political campaign speech:

peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict; while that theatre as been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union. Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defence [sic], have not arrested the plough, the shuttle, or the ship; the axe had enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore.

The second and last paragraph of the Proclamation is uncompromisingly religious. Lincoln was consciously detaching “his” Thanksgiving from its agricultural roots both by moving the holiday past harvest times and by giving the national holiday a religious justification that also attempted to soothe the wounds of war for both North and South:

And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to his tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.

Lincoln was likely sincere in his comments, but he was also a politician, up for what would probably be a bitter election in one year. He wrapped his proclamation in the trappings of religion in a way that would have horrified the Pilgrims.

Although a national Thanksgiving continued to be celebrated on the last Thursday of each November after Lincoln’s assassination, it was not officially a national holiday—technically, each Thanksgiving was proclaimed by the sitting president annually. Thanksgiving didn’t become an official national holiday with a set date until another cataclysmic event—the Great Depression. FDR decided that rather than being celebrated on the last Thursday of November, it should be on the fourth Thursday of the month. Most years, the two dates would be the same, but in 1939, there were five Thursdays in the month, just as there were earlier in his term, in 1933. In that earlier year, when the economy was in even worse shape, the business community lobbied Roosevelt to move up the date of Thanksgiving, because most Christmas shoppers waited until after Thanksgiving to start spending on gifts. During the Depression, businesses needed every break they could get. Roosevelt resisted their pressure in 1933, but acquiesced six years later.

FDR’s decision was met with all kinds of abuse. Traditionalists didn’t want to change the long-held custom. Schools and some businesses didn’t have enough time to change their vacation schedule. Calendar makers weren’t given enough lead time to make the change not just for 1939, but for 1940. All this was bad enough, but FDR was even messing up football schedules. The mayor of Atlantic City, New Jersey called the rescheduled holiday “Franksgiving.”

Many states refused to comply with FDR’s edict, which caused further problems, as families from different states couldn’t meet on a Thursday to chow down on the turkeys that the Pilgrims never ate. Twenty-three of the forty-eight states adopted November 23, 1939 as the date for Thanksgiving, while twenty-three refused to alter from November 30; two enlightened states, Colorado and Texas, honored both dates. In 1940, a few more states went along with the fourth-Thursday scheme, but finally, in 1941, Congress took the power out of the presidents’ pens and officially declared Thanksgiving to be on the fourth Thursday of November.

And so it stands, until, perhaps, another crisis comes along. The weird timing of Thanksgiving has much to do with economics, politics, religion, and tradition, and little to do with agriculture or the Pilgrims.

In a

Chicago Tribune

column, aptly dated November 25, 2005, Eric Zorn chronicles some of the oddities we have discussed, and tries to spearhead a return of the holiday to its Pilgrim roots, in October, but his motives are not just to honor history, and he’s willing to take on his state’s most illustrious politician in the process:

Thanksgiving in October would mean no need to surf the Web on Saturday evening wondering if you’ll make it back home the next day or if you’ll spend Sunday night sleeping on an airport cot or in the median of the interstate where your mini-van finally came to rest.

Lincoln didn’t know from airports or interstates, but what’s our excuse for perpetuating his mistake?

Submitted by a caller on the

Mike Rosen Show,

KOA-AM in Denver, Colorado.