What You Can Change . . . And What You Can't*: The Complete Guide to Successful Self-Improvement (14 page)

Authors: Martin E. Seligman

Tags: #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Happiness

The first,

systematic desensitization

, is Wolpe’s original. In it, the patient first learns progressive relaxation. The patient then constructs a fear hierarchy, with the worst, full-blown phobic situation at the top, and a situation that produces only the slightest phobic fear at the bottom. Susan, for example, picked meeting someone named Katz for the bottom rung, and seeing

cat

in the word

catsup

on a label on the next rung. At the top was having a real cat sit on her lap—her worst-imaginable situation.

Next, the patient goes into her practiced state of relaxation and imagines vividly the situation on the bottom rung. So Susan lay there flaccidly and imagined being introduced to an Ada Katz. She repeated this until she felt no fear at all while visualizing this. In the subsequent session, the patient once again relaxes and imagines the next-most-fearsome scene—seeing the word

cat

, in Susan’s case. She visualizes this, while relaxing, until she feels no fear at all. In about a dozen sessions, the patient will have reached the top of the hierarchy—in her imagination—without feeling fear. Once the top rung is achieved, most cat phobics find they can go from imagining cats fearlessly to actually facing real cats with little fear.

What has happened here is Pavlovian extinction. Susan repeatedly imagined the feared CS in the absence of the UR (the bodily state of relaxation precludes fear). This broke the association between cats and fear.

The other therapy,

flooding

, uses this same extinction principle. Flooding is more dramatic, but briefer. Here the phobic is thrown into the phobic situation: A claustrophobe will agree to be locked in a closet; a cat phobic will sit in a room full of cats; the agoraphobe is dropped off, in the company of the therapist, at a shopping center. In each case, the patient waits an agreed-upon length of time—it may seem an eternity, but it is actually usually around four hours—without leaving. At first the patient is terrified, but inevitably, after an hour or so, the fear starts to dissipate when she sees that no harm comes to her. After about four hours the patient is not in a state of fear anymore. She now is in the presence of the CS, but in the absence of the UR. She is exhausted and drained, but the phobic fear has extinguished.

The opposite of relaxation is used for blood phobias with marked success. In this common phobia (about 3 percent of the population has it), the victim’s heart rate and blood pressure drop sharply, and she faints at the sight of blood.

Applied tension

is taught to blood phobics. They learn to tense the muscles of the arms, legs, and chest until a feeling of warmth suffuses the face. This counterconditions the blood-pressure drop and fainting, just as relaxation counterconditions anxious tension.

7

These therapies work at least 70 percent of the time. After a brief course of such therapy, usually about ten sessions, most patients can face the phobic object. Applied tension with blood phobia works even better: Remission is lasting; former phobics rarely come to like the object, but they no longer fear it.

Unsuccessful therapy

. After extinction therapy, symptoms do not manifest themselves elsewhere. This lack of symptom substitution is important, since both psychoanalytic and biomedical theories claim that eliminating the phobia directly is merely cosmetic. The underlying conflict or the underlying biochemical disorder still exists untouched, these schools of thought have it, and symptoms must appear elsewhere. But, in fact, they do not.

Psychoanalysis does not work on phobias. Cognitive therapy, in which patients look at the irrationality of their phobias (“What really is the probability of an airplane crash?” or “Look here—no adult in Philadelphia has ever been mauled by a cat”) and learn to dispute these irrational thoughts, does not seem to be of much use for specific phobias.

8

Cognitive therapy for panic may be useful in agoraphobia, however, when panic is a central problem.

9

The Right Treatment

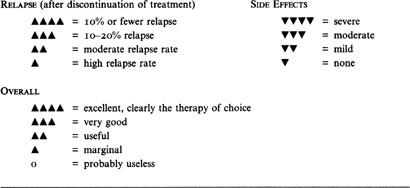

PHOBIA SUMMARY TABLE

Drugs are not very useful with object phobias. The anti-anxiety drugs produce calm when taken in high doses in the phobic situation itself, though the calm is accompanied by drowsiness and lethargy. So for an airplane phobic who must suddenly fly, a minor tranquilizer will help, but only temporarily. The calm is cosmetic: Once the drug wears off, the phobia is intact.

The combination of drugs and extinction therapy for object phobias is also probably not useful. For extinction to work, it seems necessary to experience anxiety and then have it wane. Anti-anxiety drugs block the experience of anxiety and so block extinction of anxiety. The phobia therefore remains intact.

Drugs do not seem very useful with social phobia. MAO inhibitors (strong antidepressants) have been used with some success. About 60 percent of patients improve while on these drugs. But the success is temporary and the relapse rate high once the drugs are discontinued. Remember also that MAO inhibitors have dangerous side effects (see

chapter 3

). Somewhat lower improvement (around 50 percent) occurs with the strong anti-anxiety agents, like Xanax, and with beta-blockers. But, again, the relapse rate is very high and the drugs have marked side effects. A high relapse rate upon drug discontinuation suggests only a cosmetic effect on phobic anxiety.

10

Agoraphobia, in contrast, is helped by antidepressant drugs, and in a noncosmetic way. Antidepressants seem to work to almost the same extent as extinction therapies, and they are particularly useful in combination with extinction therapies.

11

What is probably crucial is that agoraphobia, unlike most other phobias, typically involves panic attacks. Indeed, a panic attack is usually the precipitating incident in agoraphobia. Antidepressants suppress panic attacks without sedating the patient.

This is one drug effect that makes Pavlovians happy. Pavlovian theory tells us that agoraphobia starts when the CS of being in the marketplace, the agora, coincides with the UR of the panic attack. This conditions the agora to terror. When a patient is administered the combination of drug and extinction therapy, she ventures out and does not experience another panic attack, because she is drugged. She is now exposed quite effectively to the CS of the agora in the absence of the UR of panic, so Pavlovian extinction occurs.

Thus the case for phobias resulting from Pavlovian conditioning looks quite strong: Some innocent object conjoined to a terrifying trauma imbues that object with terror. As predicted, extinction therapies work quite well.

Phobias and evolution

. There are too many loose ends, however: three, to be exact. Each of these makes phobias look more like the

sauce béarnaise

phenomenon and taste aversions than like ordinary Pavlovian conditioning.

First, ordinary Pavlovian conditioning is not selective. Any CS that happens to coincide with any trauma gets conditioned. But phobias are, in fact, highly selective:

A seven-year-old on a picnic sees a snake crawling through the grass. She is interested but not disturbed by it. An hour later she returns to the family car and has her hand smashed in the car door. She develops a lifelong phobia

—

not of car doors, but of snakes!

12

There are in fact only about two dozen common phobic objects, most prominently open spaces, crowds, animals, insects, closed spaces, heights, illness, and storms. By and large these are all objects that were occasionally dangerous to our ancestors during the progress of evolution. Even the exceptions, like airplanes, are usually traceable to more primitive fear objects, like falling, suffocating, or being trapped.

13

Arne Ohman, one of Sweden’s leading psychologists, decided to find out if phobias were more like taste aversions than like ordinary Pavlovian conditioning. He performed the Garcia experiment with human fear, giving student volunteers Pavlovian conditioning with electric shock as the unconditional stimulus (US). The conditional stimulus (CS) was either an

evolutionarily prepared

object, a picture of a spider, or an

evolutionarily unprepared

object, a picture of a house. A prepared phobic object is one that has actually been dangerous to humans over evolutionary time; an unprepared object is one that has not. The students were not afraid of the spider to begin with, but after just one pairing of the spider and shock, they broke into a sweat when the spider was shown. The picture of the house induced fear—and only mildly so—only after many pairings. Unlike ordinary conditioning, then, phobic conditioning in the laboratory, the

sauce béarnaise

phenomenon, and human phobias in nature are all selective.

14

The second problem with the Pavlovian view is that conditioning requires short delays and explicit pairing of CS and US to work. Phobias don’t. There was an hour delay between the snake and the hand smashed in the car door; yet the phobia bridged this gap. Even more telling, while about 60 percent of phobics relate a story of explicit pairing of the object with a trauma to explain how it started, 40 percent do not. Rather, these phobics relate a much vaguer, more social story of the origin of their phobia: for example, they had heard that their best friend was bitten by a dog, and after that dogs always terrified them.

15

The Swedes again forged the link. Ohman showed his students the prepared object, a slide of a scorpion, and they looked at it without any fear. No explicit trauma followed. No electric shock came on. Rather, one of the students, a confederate, jumped up and raced out of the room, shrieking “I can’t stand it!” After that, the subjects sweated when they saw the slide of the scorpion.

With another group, Ohman then repeated the scenario, but with an unprepared object, a slide of a flower. Again, a shrieking student ran out in horror. But this time the subjects showed no fear at all of the flower. Evolutionarily prepared objects—though not unprepared objects—become fearful without pairing with trauma; merely seeing someone else traumatized is enough to endow them with fear.

16

The deepest problem is that ordinary Pavlovian conditioning is rational. It produces a conscious expectation that the CS will be followed by the US. But phobias are decidedly irrational. Telling a phobic that her fears are irrational (“Flying is the safest way to travel”) doesn’t dent a phobia. All of a phobic’s relatives have told her this for years, and she knows the statistics more accurately than anyone. She knows that her fears are unfounded. Cognitive therapy, unsurprisingly, does not extinguish phobias, because they are lodged in less fragile housing than reason; their roots lie deep in the unconscious. They are like my

sauce béarnaise

aversion, undented by my knowledge that the sauce was innocent and the flu guilty. Phobias can be undone, but not by talk.

Phobias, unlike panic disorders, are from Missouri. Their extinction requires the presentation of the phobic object without the UR of terror. Their extinction requires demonstration of harmlessness—flooding and desensitization.

I was a subject in one of Ohman’s crucial experiments in Sweden, the one demonstrating that prepared conditioning is irrational whereas ordinary conditioning is rational. He strapped my hand to a shock electrode and showed me a slide of a flower. Twenty seconds later, I felt a brief burst of shock. He repeated this five times. The next time the flower appeared, I was calm during the first few seconds. After about ten seconds, I began to tense up. My unease mounted so that by the nineteenth second I was sweating. I expected to be shocked after twenty seconds, and my fear had timed the interval. I showed ordinary Pavlovian conditioning. Very logical of me.