What If? (8 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

A Mole of Moles

Q.

What would happen if you were to gather a mole (unit of measurement) of moles (the small furry critter) in one place?

—Sean Rice

A

.

Th

ings get a bit

gruesome.

First, some definitions.

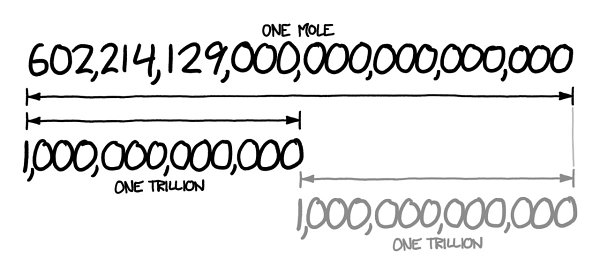

A mole is a unit. It’s not a typical unit, though. It’s really just a number

—

like “dozen” or “billion.” If you have a mole of something, it means you have 602,214,129,000,000,000,000,000

of them (usually written 6.022 × 10

23

). It’s such a big number

1

because it’s used for counting numbers of molecules, which there are a lot of.

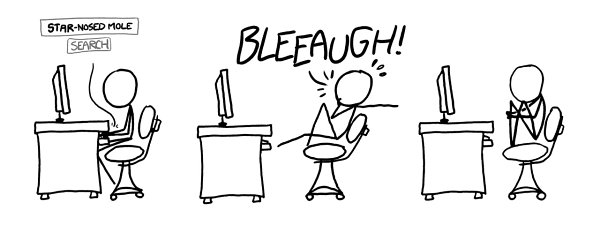

A mole is also a type of burrowing mammal.

Th

ere are a handful of types of moles, and some of them are truly horrifying.

2

So what would a mole of moles

—

602,214,129,000,000,000,000,000 animals

—

look like?

First, let’s start with wild approximations.

Th

is is an example of what might go through my head before I even pick up a calculator, when I’m just trying to get a sense of the quantities

—

the kind of calculation where 10, 1, and 0.1 are all close enough that we can consider them equal:

A mole

(the animal) is small enough for me to pick up and throw.

[

citation needed

]

Anything I can throw weighs 1 pound. One pound is 1 kilogram.

Th

e number 602,214,129,000,000,000,000,000 looks about twice as long as a trillion, which means it’s about a trillion trillion. I happen to remember that a trillion trillion kilograms is how much a planet weighs.

. . . if anyone asks, I did

not

tell you it was okay to do math like this.

Th

at’s enough to tell us that we’re talking about a pile of moles on the scale of a planet. It’s a pretty rough estimate, since it could be off by a factor of thousands in either direction.

Let’s get some better numbers.

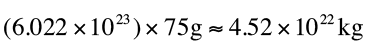

An eastern mole (

Scalopus aquaticus

) weighs about 75 grams, which means

a mole of moles weighs:

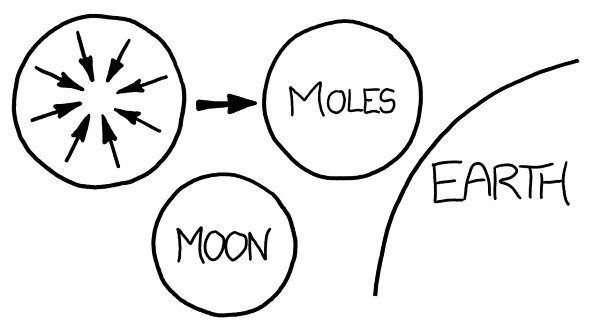

Th

at’s a little over half the mass of our moon.

Mammals are largely water. A kilogram of water takes up a liter of volume, so if the moles weigh 4.52 × 10

22

kilograms, they take up about 4.52 × 10

22

liters of volume.

You might notice that we’re ignoring the pockets of space between the moles. In a moment, you’ll see why.

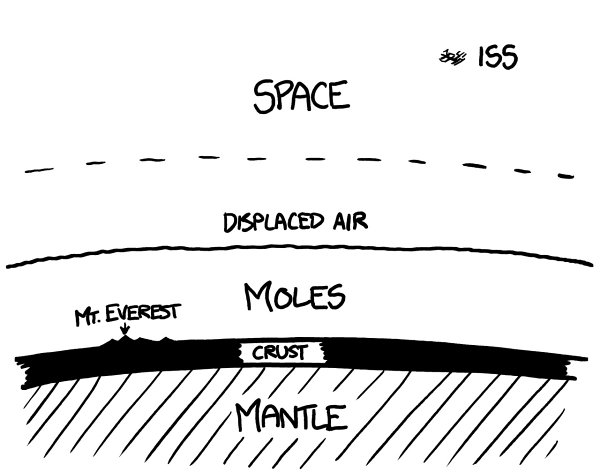

Th

e cube root of 4.52 × 10

22

liters is 3562 kilometers, which means we’re talking about a sphere with a radius of 2210 kilometers, or a cube 2213 miles on each edge.

3

If these moles were released onto the Earth’s surface, they’d fill it up to 80 kilometers deep

—

just about to the (former)

edge of space:

Th

is smothering ocean of high-pressure meat would wipe out most life on the planet, which could

—

to reddit’s horror

—

threaten the integrity of the DNS system. So doing this on Earth is definitely not an option.

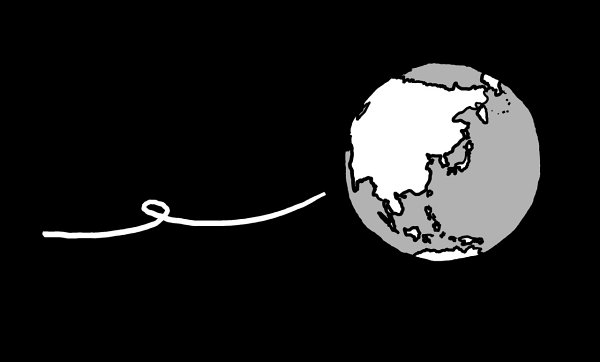

Instead, let’s gather the moles in interplanetary space. Gravitational attraction would pull them into a sphere. Meat doesn’t compress very well, so it would undergo only

a little bit of gravitational contraction, and we’d end up with a mole planet slightly larger than the Moon.

Th

e moles would have a surface gravity of about one-sixteenth of Earth’s

—

similar to that of Pluto.

Th

e planet would start off uniformly lukewarm

—

probably a bit over room temperature

—

and the gravitational contraction would heat the deep interior by a handful of degrees.

But this is where it gets weird.

Th

e mole planet would be a giant sphere of meat. It would have a lot

of latent energy (there are enough calories in the mole planet to support the Earth’s current population for 30 billion years). Normally, when organic matter decomposes, it releases much of that energy as heat. But throughout the majority of the planet’s interior, the pressure would be over 100 megapascals, which is high enough to kill all bacteria and sterilize the mole remains

—

leaving no microorganisms

to break down the mole tissue.

Closer to the surface, where the pressure would be lower, there would be another obstacle to decomposition

—

the interior of a mole planet would be low in oxygen. Without oxygen, the usual decomposition couldn’t happen, and the only bacteria that would be able to break down the moles would be those that don’t require oxygen. While inefficient, this anaerobic decomposition

can unlock quite a bit of heat. If continued unchecked, it would heat the planet to a boil.

But the decomposition would be self-limiting. Few bacteria can survive at temperatures above about 60°C, so as the temperature went up, the bacteria would die off, and the decomposition would slow.

Th

roughout the planet, the mole bodies would gradually break down into kerogen, a mush of organic matter

that would

—

if the planet were hotter

—

eventually form oil.

Th

e outer surface of the planet would radiate heat into space and freeze. Because the moles form a literal fur coat, when frozen they would insulate the interior of the planet and slow the loss of heat to space. However, the flow of heat in the liquid interior would be dominated by convection. Plumes of hot meat and bubbles of trapped

gases like methane

—

along with the air from the lungs of the deceased moles

—

would periodically rise through the mole crust and erupt volcanically from the surface, a geyser of death blasting mole bodies free of the planet.

Eventually, after centuries or millennia of turmoil, the planet would calm and cool enough that it would begin to freeze all the way through.

Th

e deep interior would be under

such high pressure that as it cooled, the water would crystallize out into exotic forms of ice such as ice III and ice V, and eventually ice II and ice IX.

4

All told, this is a pretty bleak picture. Fortunately, there’s a better approach.

I don’t have any reliable numbers for global mole population (or small mammal biomass in general), but we’ll take a shot in the dark and estimate that

there are at least a few dozen mice, rats, voles, and other small mammals for every human.

Th

ere might be a billion habitable planets in our galaxy. If we colonized them, we’d certainly bring mice and rats with us. If just one in a hundred were populated with small mammals in numbers similar to Earth’s, after a few million years

—

not long, in evolutionary time

—

the total number that have ever

lived would surpass Avogadro’s number.

If you want a mole of moles, build a spaceship.