What If? (42 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

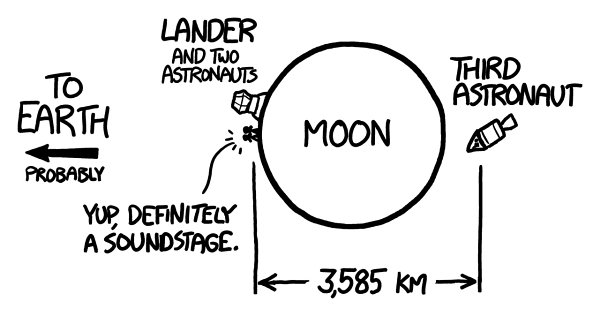

Loneliest Human

Q.

What is the farthest one human being has ever been from every other living person? Were they lonely?

—Bryan J McCarter

A.

It’s hard to know

for sure!

Th

e most likely suspects are the six Apollo command module pilots who stayed in lunar orbit during a Moon landing: Mike Collins, Dick Gordon, Stu Roosa, Al Worden, Ken Mattingly, and Ron Evans.

Each of these

astronauts stayed alone in the command module while two other astronauts landed on the Moon. At the highest point in their orbit, they were about 3585 kilometers from their fellow astronauts.

From another point of view, this was the farthest the rest of humanity has ever managed to get from those jerk astronauts.

You’d think astronauts would have a lock on this category, but it’s not so cut-and-dried.

Th

ere are a few other candidates who come pretty close!

Polynesians

It’s hard to get 3585 kilometers from a permanently inhabited place.

1

Th

e Polynesians,

who were the first humans to spread across the Pacific, might have managed it, but this would have required a lone sailor to travel awfully far ahead of everyone else. It may have happened

—

perhaps by accident, when someone was carried far from their group by a storm

—

but we’re unlikely to ever know for sure.

Once the Pacific was colonized, it got a lot harder to find regions of the Earth’s

surface where someone could achieve 3585-kilometer isolation. Now that the Antarctic continent has a permanent population of researchers, it’s almost certainly impossible.

Antarctic explorers

During the period of Antarctic exploration, a few people have come close to beating the astronauts, and it’s possible one of them actually holds the record. One person who came very close was Robert

Scott.

Robert Falcon Scott was a British explorer who met a tragic end. Scott’s expedition reached the South Pole in 1911, only to discover that Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen had beaten him there by several months.

Th

e dejected Scott and his companions began their trek back to the coast, but they all died while crossing the Ross Ice Shelf.

Th

e last surviving expedition member would

have been, briefly, one of the most isolated people on Earth.

2

However, he (whoever he was) was still within 3585 kilometers of a number of humans, including some other Antarctic explorer outposts as well as the Māori on Rakiura (Stewart Island) in New Zealand.

Th

ere are plenty of other candidates. Pierre François Péron, a French sailor, says he was marooned on Île Amsterdam in the southern

Indian Ocean. If so, he came close to beating the astronauts, but he wasn’t quite far enough from Mauritius, southwestern Australia, or the edge of Madagascar to qualify.

We’ll probably never know for sure. It’s possible that some shipwrecked 18th-century sailor drifting in a lifeboat in the Southern Ocean holds the title of most isolated human. However, until some clear piece of historic

evidence pops up, I think the six Apollo astronauts have a pretty good claim.

Which brings us to the second part of Bryan’s question: Were they lonely?

Loneliness

After returning to Earth, Apollo 11 command module pilot Mike Collins said he did not feel at all lonely. He wrote about the experience in his book

Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys:

Far from feeling lonely or

abandoned, I feel very much a part of what is taking place on the lunar surface . . . I don’t mean to deny a feeling of solitude. It is there, reinforced by the fact that radio contact with the Earth abruptly cuts off at the instant I disappear behind the moon.

I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it. If a count were taken, the score would be

three billion plus two over on the other side of the moon, and one plus God knows what on this side.

Al Worden, the Apollo

15

command module pilot, even enjoyed the experience.

Th

ere’s a thing about being alone and there’s a thing about being lonely, and they’re two different things. I was alone but I was not lonely. My background was as a fighter pilot in the air force, then as a test

pilot

—

and that was mostly in fighter airplanes

—

so I was very used to being by myself. I thoroughly enjoyed it. I didn’t have to talk to Dave and Jim any more . . . On the backside of the Moon, I didn’t even have to talk to Houston and that was the best part of the flight.

Introverts understand; the loneliest human in history was just happy to have a few minutes of peace and quiet.

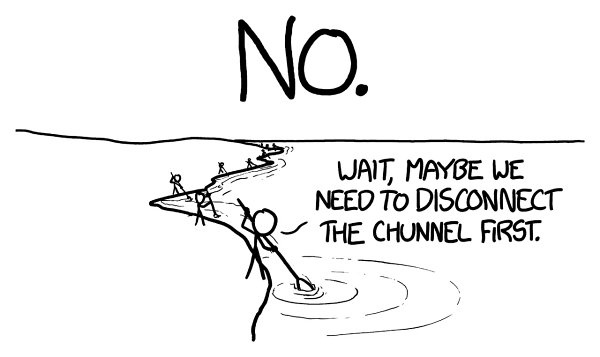

Weird (and Worrying) Questions from the What If? INBOX, #11

Q.

What if everyone in Great Britain went to one of the coasts and started paddling? Could they move the island at all?

—Ellen Eubanks

Q.

Are fire tornadoes possible?

—Seth Wishman

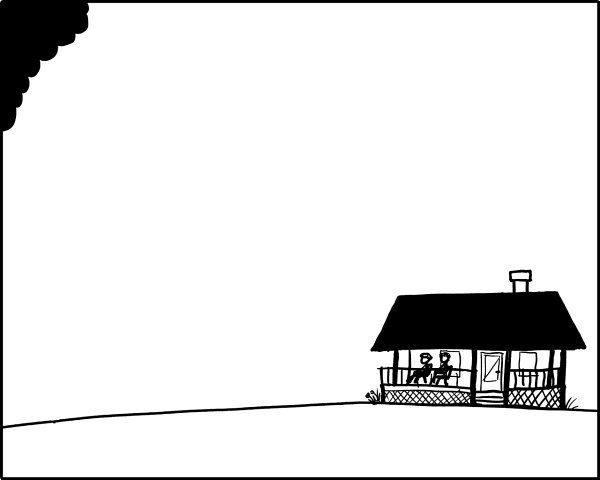

Raindrop

Q.

What if a rainstorm dropped all of its water in a single giant drop?

—Michael McNeill

A.

It’s midsummer in kansas.

Th

e air is hot and heavy. Two old-timers sit on the porch in rocking chairs.

On the horizon to the southwest, ominous-looking clouds begin to appear.

Th

e towers build as they draw closer, the tops spreading out into an anvil shape.

Th

ey hear the

tinkling of wind chimes as a gentle breeze picks up.

Th

e sky begins to darken.

Moisture

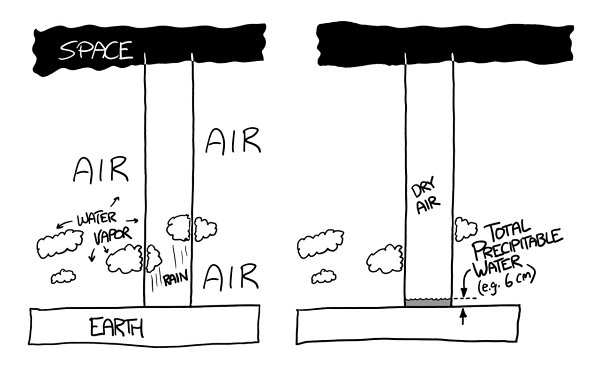

Air holds water. If you walled off a column of air, from the ground up to the top of the atmosphere, and then cooled the column of air down, the moisture it contained would condense out as rain. If you collected the rain in the bottom of the column, it would fill it to a depth of anywhere between zero and a few dozen centimeters.

Th

at depth is what we call the air’s

total precipitable water

(TPW).

Normally, the TPW is 1 or 2 centimeters.

Satellites measure this water vapor content for every point on the globe, producing some truly beautiful maps.

We’ll imagine our storm measures 100 kilometers on each side and has a high TPW content of 6 centimeters.

Th

is means the water in our rainstorm would have a volume of:

Th

at water would weigh 600 million tons (which happens to be about the current weight of our species). Normally, a portion of this water would fall, scattered, as rain

—

at most, 6 centimeters of it.

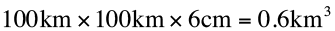

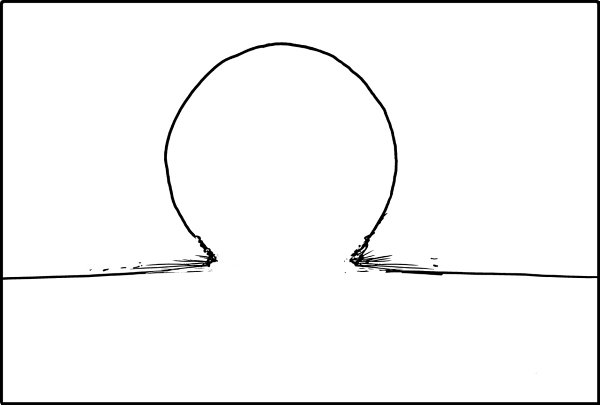

In this storm, all that water instead condenses into one giant drop, a sphere of water over a kilometer in diameter. We’ll assume it forms a couple of kilometers above the surface,

since that’s where most rain condenses.

Th

e drop begins to fall.

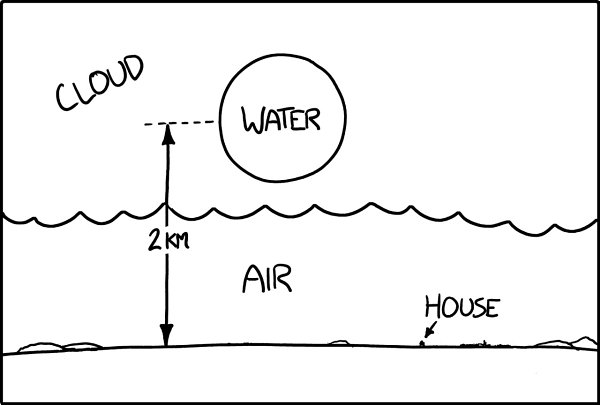

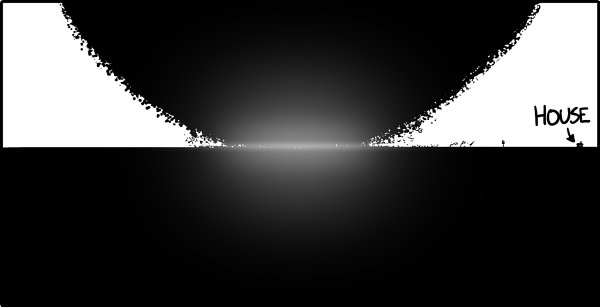

For five or six seconds, nothing is visible.

Th

en, the base of the cloud begins to bulge downward. For a moment, it looks a little like a funnel cloud is forming.

Th

en the bulge widens, and at the ten-second mark, the bottom of the drop emerges from the cloud.

Th

e drop is now falling at 90 meters per second (200 mph).

Th

e roaring wind whips up the surface of the water into spray.

Th

e leading edge of the droplet turns to foam as air is forced into the liquid. If it kept falling for long enough, these forces would gradually disperse the entire droplet into rain.

Before that can happen, about 20 seconds after formation, the edge of

the droplet hits the ground.

Th

e water is now moving at over 200 m/s (450 mph). Right under the point of impact, the air is unable to rush out of the way fast enough, and the compression heats it so quickly that the grass would catch fire if it had time.

Fortunately for the grass, this heat lasts only a few milliseconds because it’s doused by the arrival of a lot of cold water. Unfortunately

for the grass, the cold water is moving at over half the speed of sound.

If you were floating in the center of this sphere during this episode, you wouldn’t have felt anything unusual up until now. It’d be pretty dark in the middle, but if you had enough time (and lung capacity) to swim a few hundred meters out toward the edge, you’d be able to make out the dim glow of daylight.

As the raindrop approached the ground, the buildup of air resistance

would lead to an increase in pressure that would make your ears pop. But seconds later, when the water contacted the surface, you’d be crushed to death

—

the shockwave would briefly create pressures exceeding those at the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

Th

e water plows into the ground, but the bedrock is unyielding.

Th

e pressure forces the water sideways, creating a supersonic omnidirectional

jet

1

that destroys everything in its path.

Th

e wall of water expands outward kilometer by kilometer, ripping up trees, houses, and topsoil as it goes.

Th

e house, porch, and old-timers are obliterated in an instant. Everything within a few kilometers is completely scoured away, leaving a pool of mud atop bedrock.

Th

e splash continues outward, demolishing all structures out to distances of 20 or 30 kilometers. At this distance,

areas shielded by mountains or ridges are protected, and the flood begins to flow along natural valleys and waterways.

Th

e broader region is largely protected from the effects of the storm, though areas hundreds of kilometers downstream experience flash flooding in the hours after the impact.

News trickles out into the world about the inexplicable disaster.

Th

ere is widespread shock and

puzzlement, and for a while, every new cloud in the sky causes mass panic. Fear reigns supreme as the world fears rain supreme, but years pass without any signs of the disaster repeating.

Atmospheric scientists try for years to piece together what happened, but no explanation is forthcoming. Eventually, they give up, and the unexplained meteorological phenomenon is simply called a “dubstep

storm,” because

—

in the words of one researcher

—

“It had one hell of a drop.”

- 1

Just about the coolest triplet of words I’ve ever seen.