What If? (20 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

- 1

“Virii” is used occasionally but discouraged. “Viræ” is definitely wrong.

- 2

Any upper respiratory infection can actually be the cause of the “common cold.”

- 3

Th

e immune response is actually the cause of your symptoms, not the virus itself.

- 4

Mathematically, this must be true.

If the average were less than one, the virus would die out. If it were more than one, eventually everyone would have a cold all the time.

- 5

(450 million people).

- 6

(650 million people).

- 7

I first tried to take the question to

Boing Boing

’s Cory Doctorow, but he patiently explained to me that he’s not actually

a doctor.

- 8

Th

e residents of St. Kilda correctly identified the boats as the trigger for the outbreaks.

Th

e medical experts of the time, however, dismissed these claims, instead blaming the outbreaks on the way the islanders stood around outdoors in the cold when a boat arrived, and on their celebrating the new arrivals by drinking too much.

- 9

Unless we ran out of food during the quarantine and all starved to death; in that case, human rhinoviruses would die with us.

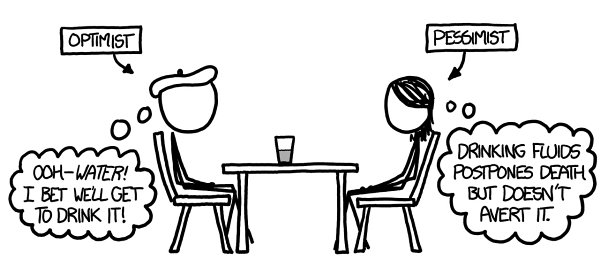

Glass Half Empty

Q.

What if a glass of water was, all of a sudden, literally half empty?

—Vittorio Iacovella

A.

Th

e pessimist is probably

more right about how it would turn out than the optimist.

When people say “glass half empty,” they usually mean a glass containing equal parts water and air.

Traditionally, the optimist sees the glass as half full while the pessimist sees it as half empty.

Th

is has spawned a zillion joke variants

—

for example, the engineer sees a glass that’s twice as big as it needs to be, the surrealist sees a giraffe eating a necktie, etc.

But what if the empty half of the glass were

actually

empty

—

a vacuum?

1

Th

e vacuum would definitely not last long.

But exactly what happens depends on a key question that nobody usually bothers to ask:

Which

half is empty?

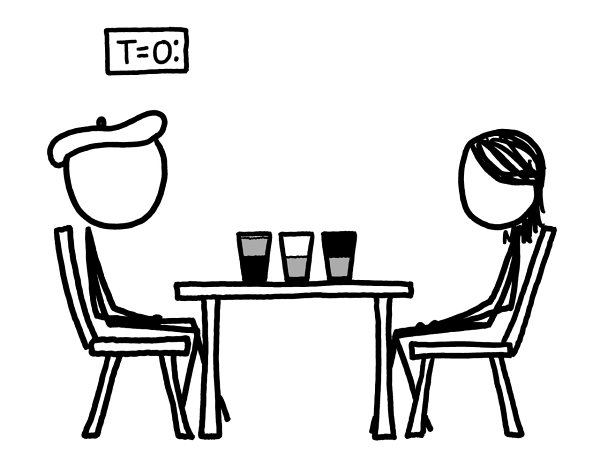

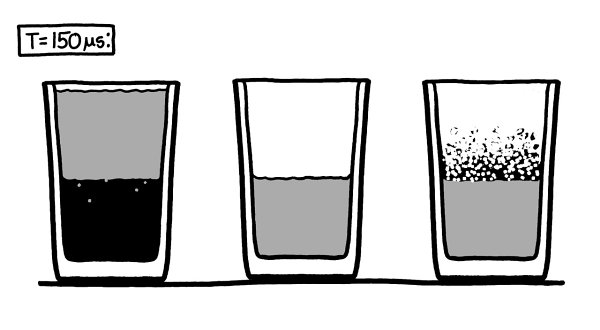

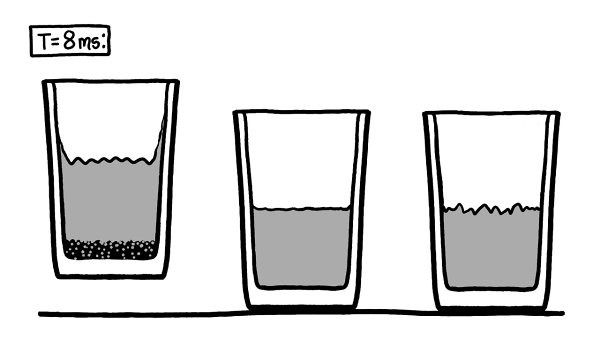

For our scenario, we’ll imagine three different half-empty glasses, and follow what happens to them microsecond by microsecond.

In the middle is the traditional air/water glass. On the right is a glass like the traditional one, except the air is replaced by a vacuum.

Th

e glass on

the left is half full of water and half empty

—

but it’s the bottom half that’s empty.

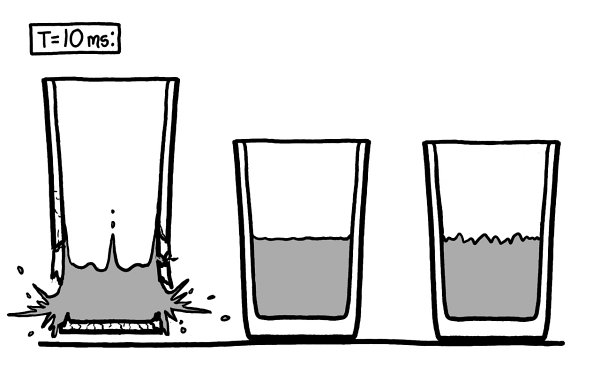

We’ll imagine the vacuums appear at time

t

=0.

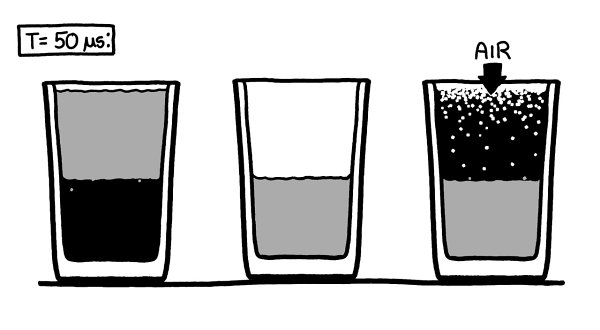

For the first handful of microseconds, nothing happens. On this timescale, even the air molecules are nearly stationary.

For the most part, air molecules jiggle around at speeds of a few hundred meters per second. But at any given time, some happen to be moving faster than others.

Th

e fastest few are moving at over 1000 meters per second.

Th

ese are the first to drift into the vacuum in the glass on the right.

Th

e vacuum on the left is surrounded by barriers, so air molecules can’t easily get

in.

Th

e water, being a liquid, doesn’t expand to fill the vacuum in the same way air does. However, in the vacuum of the glasses, it does start to boil, slowly shedding water vapor into the empty space.

While the water on the surface in both glasses starts to boil away, in the glass on the right, the air rushing in stops it before it really gets going.

Th

e glass on the left continues to fill with a very faint mist of water vapor.

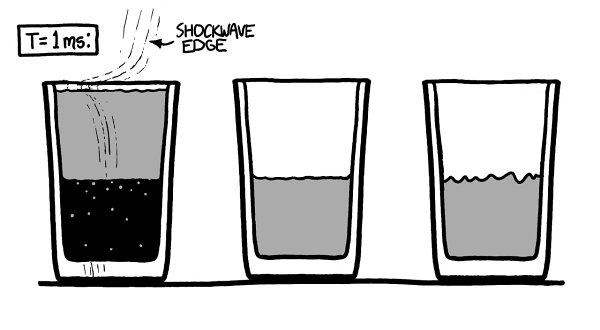

After a few hundred microseconds, the air rushing into the glass on the right fills the vacuum completely and rams into the surface of the water, sending a pressure wave through the liquid.

Th

e sides of the glass bulge slightly, but they contain the pressure and do not break. A shockwave reverberates through the water and back into the air, joining the turbulence already there.

Th

e shockwave from the vacuum collapse takes about a millisecond to spread out through the other two glasses.

Th

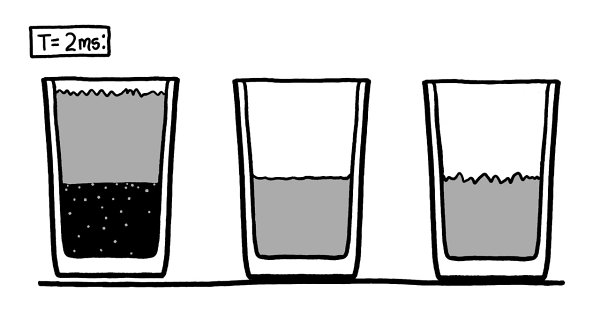

e glass and water both flex slightly as the wave passes through them. In a few more milliseconds, it reaches the humans’ ears as a loud bang.

Around this time, the glass on the left starts to visibly lift into the air.

Th

e air pressure is trying to squeeze the glass and water together.

Th

is is the force we think of as suction.

Th

e vacuum on the right didn’t last long enough for the suction to lift the glass, but since air can’t get into the vacuum on the left, the glass and the water begin to slide toward each other.

Th

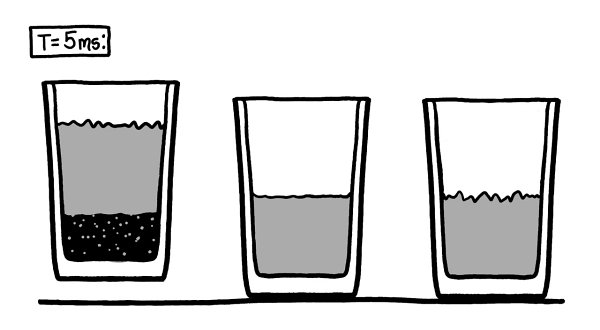

e boiling water has filled the vacuum with a very small amount of water vapor. As the space gets smaller, the buildup of water vapor slowly increases the pressure on the water’s surface. Eventually, this will slow the boiling, just like higher air pressure would.

However, the glass and water are now moving too fast for the vapor buildup to matter. Less than ten milliseconds after the clock started, they’re flying toward each other at several meters per second. Without a cushion of air between them

—

only a few wisps of vapor

—

the water smacks into the bottom of the glass like a hammer.

Water is very nearly incompressible, so the impact

isn’t spread out over time

—

it comes as a single sharp shock.

Th

e momentary force on the glass is immense, and it breaks.