Welcome to Your Brain (35 page)

Read Welcome to Your Brain Online

Authors: Sam Wang,Sandra Aamodt

Tags: #Neurophysiology-Popular works., #Brain-Popular works

folklore does not have any experimental proof, but is likely to have its roots in the observation that

dreams often incorporate the daily concerns of the dreamer, combined with seemingly random or

senseless events. The existence of trains of thought in dreams and a degree of plot suggests that your

cortex has some ability to construct a coherent story from what it is given—though this may simply

reflect the action of the “interpreter” discussed in

Chapter 1

. In that respect, dreams may constitute a

means of sampling what’s lying around in your head. When we talk about our dreams, we focus on the

extent to which our dreams can be made coherent: waking up in class naked, sailing a ship, rolling a

big rock. But what if the random aspects of dreaming are an essential feature? What if randomly

sampling the brain’s contents as we sleep is a means for transferring our memories to a more

permanent place? Resampling could even be used to correct wrong memories that need to be erased.

Weird dreams may be the price, or perhaps an unintended benefit, of the mechanisms that our brains

use to remember the events of our lives.

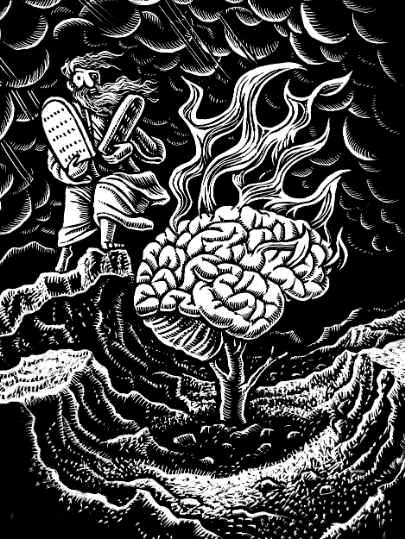

A Pilgrimage: Spirituality

How religion is rooted in our biology has been a popular topic for recent books, especially among

atheists who are convinced that religious beliefs are irrational. Prime examples are

The God

Delusion

by biologist and bomb thrower Richard Dawkins and

Breaking the Spell: Religion as a

Natural Phenomenon

by philosopher Daniel Dennett. Considering how little is known about the

neuroscience of religion, it seems premature to claim that biologists have the issue all worked out.

Anthropologists have expressed a more positive view of religion: that it was a powerful early

instrument of group social bonding, which may have provided a survival advantage for religion itself

and for humans who shared the beliefs. Let’s start by reminding ourselves that organized religion is a

remarkable achievement, one of the most sophisticated cultural phenomena in existence. Consider the

basic elements of most religions: believers have elaborate cognitive representations of a supernatural

force that cannot be seen. We plead with the force to reduce harm, bring about justice, or provide

moral structure. We furthermore create an understanding with our fellow humans that this force sets

the same standards of morals, social norms, and religious rituals for all of us. It’s a complicated

business, unique to us among all living beings.

What can neuroscience contribute to our understanding of religion? In one sense, nothing: the

satisfaction derived from religion is unlikely to be changed much by knowing how the brain gives rise

to beliefs. Just as you can use words profitably for a lifetime without understanding formal grammar,

people can benefit from religious belief—and for that matter, many other systems analyzed in this

book—without understanding its basis in the brain. Still, if you’ve come this far, you might be

curious.

Two brain capabilities are particularly important in the formation and transmission of religious

belief. Many animals probably have some form of the first trait: the search for causes and effects. The

second trait, social reasoning, is unusually highly developed in humans. One of the core skills of the

human brain is the ability to reason about people and motives—what scientists call a theory of mind.

The combination of these abilities has generated key features of mental function that are part of

religious belief: our ability to make causal inferences and abstractions, and to infer unseen intentions,

whether they’re the intentions of a deity or some other entity. Neural mechanisms that favor the

formation of religious beliefs are also likely to favor the formation of organized belief movements of

other kinds, including political parties, Harry Potter fan clubs—and militant atheism.

What kind of god would it be who only pushed the world from the outside?

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Most religions seek causes for events in the world. These explanations often take the form of

actions performed by a thinking entity. For example, small children either explicitly or implicitly

assign motives to inanimate objects. Developmental psychologists find that small children think a ball

rolls because it wants to. This way of thinking is so natural to us that we do not hesitate to think of

everyday objects as having personalities. We often assign cars or other machines personalities and

even names. Teakettles whistle cheerily, and storms rage. It seems natural, then, that early humans

might have applied such reasoning to the events of the natural world. This kind of reasoning is seen in

animist religions, which attribute a spirit to living and nonliving objects.

Applying the metaphor of conscious agency to natural events becomes something new when

combined with our intensely social nature. We dedicate considerable mental resources to

understanding others’ motivations and points of view. The growing complexity of a child’s view of

motivation can be seen in play, which starts with simple sensory activation but quickly blossoms into

first-order pretense (“I’m a wagon!”) to baroque role-playing (“Okay, now you pretend to be the

child, and I will pretend that I’m the teacher and the class is making too much noise”).

The attribution of imaginary motives to oneself and to others requires a theory of mind. This

ability allows children to engage in fictional play, like pretending that a toy soldier can fight. As they

acquire a theory of mind, children realize that others have motivations, which they can use in innocent

ways, such as games of hide-and-seek, but also to more nefarious ends, like misleading another

person. At later stages, the sophistication of pretense becomes even more complex; children develop

the ability to understand a staged drama. In

Chapter 24,

we explained that people with autism have

difficulty in understanding that others have motivations and desires, which has profound and

sometimes disastrous effects on their dealings with the world. So the theory of mind is central to our

sense of ourselves and of others.

Assessment of social scenarios requires activity in many cortical areas. One example is mirror

neurons, which fire both when a monkey performs a task and when he sees another monkey do the

same task (see

Chapter 24)

, suggesting that the monkey’s brain understands that the two actions share

something in common. In addition, social communication is impaired in monkeys with damage to the

amygdala (see

Chapter 16)

, a brain structure intimately involved in deriving the emotional

significance of objects and faces, and therefore critical in giving the brain access to knowledge of the

mental states of others. All this brain machinery is likely to be involved in our attempts to explain

things like natural events and complex relationships among nonhuman or inanimate objects.

Religious belief is made possible when the drive for causal explanations is combined with our

brains’ ability—and propensity—to provide advanced levels of social cognition. Together, these two

abilities allow us to generate complex cultural ideas ranging from jaywalking to justice, redemption

to the Resurrection. As we noted in

Chapter 3,

complex social reasoning is related to cortical size.

This strong relationship implies that social cognition requires some serious information-processing

horsepower. The brain arms race that rewarded our ability to cooperate with and outsmart our fellow

beings has also set the stage for religious mental constructs. As a consequence, we can imagine a

God, Yahweh, or Allah that is the cause of everything and judges us, yet who cannot be seen.

Did you know? Meditation and the brain

The Dalai Lama says that when scientific discoveries come into conflict with Buddhist

doctrine, the doctrine must give way. He also has a strong interest in exploring the neural

mechanisms underlying meditation. Like many practitioners, he divides meditation into two

categories: one focused on stilling the mind (stabilizing meditation) and the other on active

cognitive processes of understanding (discursive meditation). Neuroscience’s first pass at

studying meditation focused on the first category. Brain activity in highly skilled

practitioners of stabilizing Buddhist meditation was evaluated by a group of scientists,

including one with a Ph.D. in molecular biology who has since joined the Shechen

Monastery in Nepal as a disciple.

The group was able to draw eight long-term practitioners of Tibetan Buddhist

meditation away from their normal practice (which is spending all day in meditative

retreats). In the laboratory, the monks had electrodes placed on their heads to measure

patterns of electrical activity. At first, the patterns were no different than those of

volunteers meditating for the first time. The difference came when the monks were asked to

generate a feeling of compassion not directed at any particular being, a state that is known

as objectless meditation. Under this condition, the activity began varying in a coherent,

rhythmic manner, suggesting that many neural structures were firing in synchrony with one

another. The increase in the synchronized signal was largely at rates of twenty-five to forty

times per second, a rhythm known as gamma-band oscillation. In some cases, the gamma

rhythms in the monks’ brain signals were the largest ever seen in people (except in

pathological states like seizures). In contrast, naïve meditators couldn’t generate much

additional gamma rhythm at all.

How brains generate synchronization is not well understood, but gamma rhythms are

greater during certain mental activities, such as attending closely to a sensory stimulus or

during maintenance of working memory. This increased gamma-band rhythm may be a key

component of the heightened awareness reported by monks. Are monks born with a natural

ability to generate a lot of brain synchrony? Several types of rhythm seem to get stronger

with experience in novices who learn meditation, suggesting that the capacity is at least

partly trainable.

Brain scanning also identified regions that are active during discursive meditation

(focused attention on a visualized image). Anterior cingulate and prefrontal areas of the

cortex were very active, as they are when Carmelite nuns recall the feeling of mystical

union with God. This work fits with the involvement of these regions in attention. It

probably would also have been of interest to Pope John Paul II, who, in reference to

science and Catholic doctrine, said that they were both true and compatible with one

another because “truth cannot contradict truth.”

If theory of mind is a critical factor in the formation of religion, then animals that display some

kind of theory of mind might be capable of religious belief. Can animals form a mental model of what

others are thinking? In some species, the answer might be yes. For example, consider our friend

Chris’s dog Osa. Because of an injury, Osa was temporarily unable to climb stairs by herself, and

Chris had to carry her up and down. This persisted for months, with her waiting at the top or bottom

of the stairs to be carried. One day Chris came home at midday and was quietly puttering around in

the kitchen. Osa came down the stairs, walking. Halfway down, she saw Chris and froze with a look

that seemed to say, “I am so busted,” which, of course, she was. Osa appeared to be acting on the

assumption that if Chris knew she could walk down stairs, he would stop carrying her. This suggested

to Chris that she could visualize what made Chris tick, at least when it came to schlepping pets up and

down the stairs.

It’s a gigantic leap to assign a theory of mind based on a single look from a dog. One could just as

well say that the story demonstrates Chris’s own theory of mind. However, in more systematic

studies, dogs do appear to take into account other dogs’ attentional states when trying to persuade

them to participate in play, adjusting the signals they send according to what the other dog is doing.

Ethologists and anthropologists study the degree of sophistication of theory of mind by counting

how many levels of intention can be imagined. Osa’s desire to deceive sits at a relatively simple