We Two: Victoria and Albert (74 page)

Read We Two: Victoria and Albert Online

Authors: Gillian Gill

And so, in the spirit of sublime self-sacrifice, Victoria determined to live for her country and her children. The unworthy Bertie must wait for the throne. Her mission was clear: to represent the sainted Albert on earth, voice his views, realize his vision. Pleasure must be put aside. The stony path of duty must be trodden with bleeding feet.

And having Albert in eternal bliss, impatiently awaiting her, instead of on earth, busy running her kingdom for her, had its advantages. From early in their marriage, both she and Albert had used the pronoun

we

for their joint life, their joint enterprise, and their joint policy, but more and more with the years “we” had meant “I, Albert, in Victoria’s name and taking her consent for granted.” Now speaking as Albert and Victoria, male and female, she could reclaim the ancient royal “we” and speak with as much authority as her male predecessors. As an unmarried queen, Victoria had delighted in having her way. Yielding to Albert’s will and taking him as her lord and master had gone against the grain. Now, as the dead man’s disciple, citing his example, preaching his gospel, she would again be master in her own household, head of the family, the sacred embodiment of the Crown. “I am also anxious to repeat one thing,” wrote Victoria to her uncle Leopold ten days after Albert’s death, “and

that

one is my

firm

resolve, my

irrevocable

decision, viz that

his

wishes—

his

plans—above everything

his

views about everything are to be

my law!

And no

human power

will make me swerve from what

he

decided … I am

also determined

that

no one

person, may

he

be ever so good, ever so devoted among my servants—is to lead or guide or dictate

to me

.“

The Latin word order of the inscription placed on the coffin of the dead prince—“

Augustissimae et potentissimae Victoria Reginae conjugis percarissimus”

—makes the point very well. Her Most Puissant and August Majesty, Queen Victoria, asserts ownership of a most beloved, dead husband.

FOR AT LEAST

three years, Queen Victoria was very, very unhappy, but she coped, and she had compensations—first and foremost the process and ritual of mourning, which had always held a peculiar fascination for her. The Queen’s dressers always had her mourning clothes ready in case a distant relative or dim European duke should die. Now the Queen had the satisfaction of seeing every person she met, from the youngest princess to the scullery maid, wreathed in dull black from head to toe. In 1864, court ladies were at last permitted to wear gray, white, and purple, but mauve was still considered too frisky.

For the rest of her life, Queen Victoria’s wardrobe was uniformly black and unadorned. Plain, high-necked gowns replaced the low-cut, elaborately embroidered pink and blue creations of the Queen’s married years. On her head, ugly caps with the widow’s peak replaced the flowers and wheat ears, the ropes of pearls and diamond tiaras. The fabulous display of jewelry ceased, and the Queen agreed to wear a tiny new crown around her bun only on rare state occasions. The message was clear. The Queen had never cared for fashion, only for her husband’s compliment. Why bare her shoulders, put diamonds on her breast, and dress her hair when there was no one to comment on her beauty?

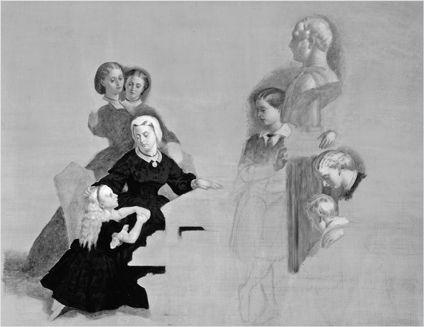

The newly widowed Queen with her children

To reinforce and publicize the message, the newly widowed Queen sat for a remarkable number of oil paintings and photographs. The painted portraits were copied and distributed to close family and friends. The photographs were for the public as much as the family album. Seated next to a bust of the prince consort, the Queen appears young and comely in a painting by Albert Graefle. She wears a severe black dress and white widow’s cap, but an ermine robe stretched fancifully over the back of her chair marks the fact that she is queen as well as widow. A photograph of her in a big black hood and fur-trimmed dress shows her looking down somberly at a little miniature of the prince. Several photos show her surrounded by ashen-faced children, her face turned in adoration to the bust of the prince or gazing at his portrait in her lap. Years later, in the portraits of the Queen surrounded by her children and their spouses and their children, some representation of the dead prince consort would always be included.

A vital task facing the Queen within hours of her husband’s death was to create her own clean and sanitary version of what the Germans called a

sterbe-zimmer—

a death chamber. Photographers were called in at once to capture the appearance of the Blue Room as the prince left it at 10:50 p.m., December 14, 1861. Repainted, kept meticulously clean, with fresh flowers strewn on the bed daily, the room was kept for the Queen’s lifetime as if Albert might at any moment walk back into it and take up his life again. The towels were changed, and hot water was brought in for shaving each day. The glass with the last dose of medicine lay on the bedside table, and the blotting book lay open next to the pen on the writing table.

Such death chambers were not uncommon—there were several, shrouded in cobwebs, in the vast royal warrens of Berlin. But Victoria had no intention of stopping there. Her pleasure was to create sacred spaces where she could commune with the dear departed. Her duty was to ensure dearest Albert’s place in history and keep his example before the ungrateful world.

And so, whatever the desolation that overwhelmed her at night, that kept her for years from the public’s view, and made the lives of her family and her court miserable, the Queen was all activity and business during the day. Within days of the death, she was begging the crown princess in Berlin “to help me in all my great plans for a mausoleum (which I have chosen the place for at Frogmore) for statues, monuments, etc.” The Italian sculptor Marochetti, the German painters Winterhalter and Grüner, who had enjoyed the prince’s patronage, were admitted to see the widowed Queen even before the 1861 Christmas holiday began. Over the next year, architects, sculptors, painters, and artists in glass and ceramic were busily planning

for the transformation of St. George’s Chapel at Windsor to accommodate the Albert Memorial Chapel and the construction and decoration of the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore on the grounds of Windsor Castle.

The Queen at the outset keenly studied all the proposed memorials across the nation. She contributed her own money but was also an efficient fund-raiser with parliament and private groups. She was anxious to show Albert as she remembered him: young, handsome, athletic, virile. A rare moment of disagreement between the Queen and her daughter in Prussia occurred when Vicky attempted a bust of her father and made the nose, in her mother’s opinion, too thick. For several years, the only occasions when the Queen could be persuaded to appear in public was for the unveiling of a statue of her husband—in Windsor Great Park, at Balmoral, in Aberdeen, in Coburg.

For the Queen, the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore was the most important monument. Here, barely a year after his death, Albert’s coffin was transported, to lie in a massive sarcophagus surmounted by a statue by Carlo Marochetti. Here, accompanied by her daughters and her ladies, Victoria came to weep in the early days of her widowhood. Here she came with members of her family each year on sacred anniversaries until the end of her life. Here Victoria herself would be buried by Albert’s side, under a statue that Marochetti also made in the 1860s, capturing the Queen in eternal, and idealized, youth. Even today the mausoleum at Frogmore is open to the public for only a few hours a year and is known almost exclusively from pictures.

The most important monument from the nation’s point of view was the National Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, just a stone’s throw from the Royal Albert Hall, itself fronted by a huge statue of the prince in a Shakespearian doublet. The Victoria and Albert Museum, whose seed money came from the Great Exhibition of 1851, is close by. The first planning meeting for the memorial occurred within a month of the prince’s death, and the London municipal worthies decided that even though the project was to be publicly funded, the Queen should be allowed to choose the design. Her choice, a monument by George Gilbert Scott, the most famous and most pompous of Victorian architects, was slowly completed over the next fourteen years. Perhaps because people had been able to watch the huge thing go up stage by stage, or because the nation and the royal family had by 1876 finally tired of unveiling statues to a dead prince, there was no inauguration ceremony.

The Albert Memorial, as it came to be known, features a seated prince, dressed in Garter robes, court breeches, and pumps, the catalog of the Great

Exhibition of 1851 in his hand. Over the giant bronze statue rears an immense, gilded, Gothic-style canopy, making the monument into a shrine. Surrounding and beneath the main figure is a complex of statuary by various British artists. On the four corners are figures representing the continents of Europe, Asia, Africa, and America. Australia had certainly been “discovered” by the 1860s, but presumably it upset the symmetry and so failed to make the cut.

BY 1864, QUEEN VICTORIA

was still almost invisible to the public, but her household noticed that she was beginning to recover her zest for life. This was due in part to the simple passage of time but also to the presence by her side of a Scotsman named John Brown.

Albert had filled many key functions in Victoria’s life and, as the years went by, she found that many of those functions could be filled quite effectively by ministers, secretaries, comptrollers, and the like. But Victoria still had two unmet affective needs that servants of the Crown such as Benjamin Disraeli, Henry Ponsonby and Charles Grey could not fill. She wanted to feel safe and protected, and she wanted to be number one in the life of at least one person. John Brown emerged to meet those needs, and from about 1864, when he became a year-round member of her household, to 1883 when he died, Brown was essential to her. Heart and soul, he was her liege man, and he devoted his life to her at no small cost.

John Brown was a Highlander, a tall, strong, handsome man, seven years younger than the Queen, who was first employed on the Balmoral estate as a gillie, working with the horses and dogs, managing the game, working as a beater and loader, leading the ponies on royal excursions. Brown won the commendation of the prince consort for his good sense and loyalty, and he then became a favorite with the Queen. When the widowed Victoria returned to Balmoral, Brown not only led her pony on the steep trails but drove out with her on her excursions in a pony chaise. His courage and resourcefulness were credited with saving her life on several occasions. In 1864 she decided that Brown was too important to her comfort to be left behind in Scotland, and so he was promoted, given the title of the Queen’s Highland Servant, allotted a new set of suits, and brought to Osborne and Windsor. Brown quickly graduated from cleaning the Queen’s boots and washing her dogs to serving as her personal attendant, messenger, and intermediary, to becoming her favorite companion.