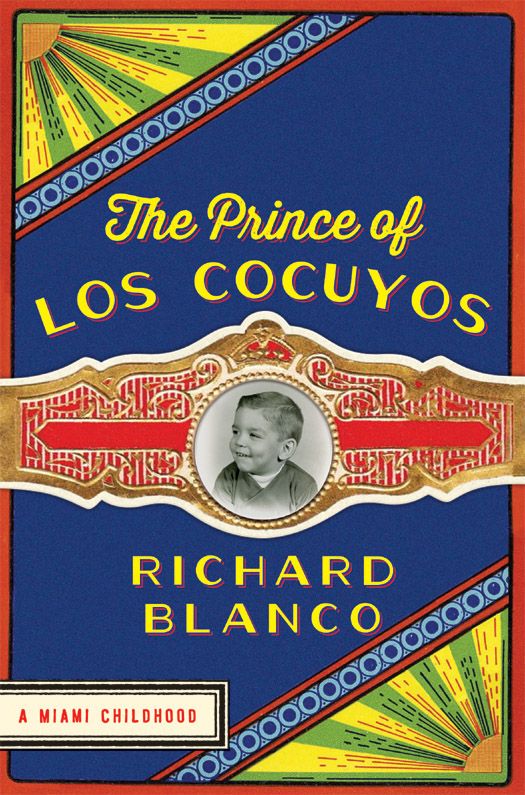

The Prince of los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood

Read The Prince of los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood Online

Authors: Richard Blanco

For Carlos “Caco” Blanco, El Guayo:

my confidant, babysitter, cohort,

superhero, ally, friend, and brother,

who has been and will be with me always

You need a village, if only for the pleasure of leaving it. Your own village means that you’re not alone, that you know there’s something of you in the people and the plants and the soil, that even when you are not there it waits to welcome you

.

—

CESARE PAVESE

1

THE FIRST REAL SAN GIVING DAY

T

he act of becoming is one of two fundamental human acts, the other being loving. And we can’t love without becoming, or become without loving. I have loved and I have become thanks to

mi familia

. My mother, Geysa, the woman with the prettiest name and one of the saddest and most beautiful stories in the world. My father, Carlos, who died before I could love him as much as I wanted to love him or thank him for naming me after Richard Nixon. My only brother, Carlos, a fixed star in my life who means more to me than I can express in these pages. My

abuelo,

Carlos (yes, all three of them were named Carlos!), who suffered through every one of my strikeouts at bat and yet kept cheering me on. And my

abuela,

Otmara: these pages have let me hate her, understand her, forgive her, and thank her for her failed attempts at “making me

un hombre,

” which indirectly made me a writer.

Te quiero, Abuela

.

Beyond them, all my

tíos

and

tías,

especially Miriam, Toti, Emiliano, Magdalena, Olga, Armando, Pedro, and Elsa. Without them—their stories, their longing, and their memories—this book of my memories would not exist. My thanks also to all my

primos

and

primas,

especially Helen, Brenda, Mirita, Normi, Gilbert, and Bernie. I am who I am because you are who you are. And beyond them, my neighbors,

bodegueros,

teachers (especially Miss De Vos), buddies (Angel and Alex), girlfriends (especially Anabelle), and boyfriends (Darden, Michael, and Carlos). In other words: my entire village,

mi pueblo entero

.

Fast-forward to the days when I first desired to translate my experiences from poetry into prose and discover what my life would read like without line breaks. My thanks to Stuart Bernstein and Ruth Behar, who ushered me into the genre of memoir, and to Bill Clegg, who helped me think about these pages differently. I am indebted to Frank Cimler, who found a perfect home for this book at Ecco. And so, my thanks to Dan Halpern for believing in this story and agreeing to publish it.

Fast, fast-forward to the days of shaping my raw words into this book with my editor Libby Edelson at Ecco. We began to finish each other’s sentences; she understood this book better than me, and at times, she understood me better than I understood myself. It was a literary love affair, still going strong. And later, Hilary Redmon, also at Ecco, who shed more light on these pages. In the final round, Leonard Nash, who scrutinized this book with an incredibly keen eye and tied up

many loose ends that made a huge difference.

And there were others, as always, who helped me write and believe, believe and write. Among these, Alison Granucci, my literary fairy godmother, who continues to be a guiding light; Felicitas Thorne, who gave me much-needed time and space to finish part of this book; and, of course, my husband, Mark, who inspires me every day—not just to write, but to live and love.

M

y childhood continues to amaze me as a constant reference point for who I’ve been, who I am, and who I will be. It feels concrete and accessible but, on some level, also elusive and fractured. As such, these pages are emotionally true, though not necessarily or entirely factual. Certainly, I’ve compressed events; changed the names of people, places, and things; and imagined dialogue. At times I have collaged two (or three) people into one, embroidered memories, or borrowed them. I’ve bent time and space in the way that the art of memory demands. My poet’s soul believes that the emotional truth of these pages trumps everything. Read as you would read my poems, trusting that what is here is real, beyond what is real—that truer truth which we come to call a life.

A

ccording to my

abuela

, once the revolution took hold in the midsixties, “

No había nada

. Castro rationed everything. Two eggs a week,

una libra

of rice every month, and two cups of

frijoles negros,

if there were any. There wasn’t even any

azúcar

. Imagine Cuba without sugar!” she’d complain in her crackly voice. “

Gracias a Dios,

your

abuelo

worked at the sugar mill in Hormiguero.” Every week, Abuela made sure he took home double or triple his sugar quota. With the extra pounds, she cooked up vats of

dulce de leche

and guava marmalade. She also traded with the town baker—a few cups of sugar for a few stale loaves she’d use to bake her homemade

pudín de pan

. She sold her confections on the black market, and in two years made enough money to buy visas and plane tickets to get the whole family out of Cuba.

A few months after we arrived in New York City, Abuela started her own business, sort of. Once a week she took the bus downtown to the discount stores and bought girdles, scented soaps, cigarette lighters, chocolate-covered cherries, alarm clocks, gold-plated earrings—anything of “quality” that she could mark up and resell door-to-door to the

puertoriqueñas

in our apartment building. “Those

muchachas

buy any

mierda

you bring to their door. They’re too lazy to find the good prices,” she would say. Abuela also worked at a purse factory, sewing the linings of the bags. Far shy of five feet tall and stocky, she wasn’t exactly a bombshell, but that didn’t stop her from using her broken English to sweet-talk her

americano

foreman into letting her buy the scuffed-up purses wholesale. She would then cover up the scratches with her eyebrow pencil and sell them at full price, good as new.

When we moved to Miami, Abuela became a bookie for

La bolita,

an illegal numbers racket run by Cuban mafiosos. She took bets all day long, recording them on a yellow legal pad and calling them in every night to Joaquín, the big boss. She also sold Puerto Rican lotto tickets, which she marked up twenty cents. Every month Graciela, her contact in San Juan, would send a stack of tickets; in exchange, Abuela split the profits with her: 25 percent for Graciela, 75 percent for herself. On Saturday nights, I’d help Abuela with her bookkeeping for the week. We’d set up at the kitchen table, her disproportionately large bust jutting out and over the tabletop and her short legs that didn’t reach the floor swinging back and forth underneath the chair. “Make sure all the

pesos

are facing up—and all the same way,” she instructed every time we’d begin sorting the various denominations into neat stacks.

As we handled the bills I tried teaching her about the father of our country, the Gettysburg Address, the Civil War, and the other bits of American history I was learning in school.

Who’s this? What did he do?

I’d quiz her, pointing at the portrait of Jackson, his wavy hairdo and bushy eyebrows, on a twenty; or at Lincoln’s narrow nose and deep-set eyes on a five. But it was useless: “

Ay, mi’jo,

they’re all

americanos feos

. I don’t care who they are, only what they can buy,” she’d quip, thumbing through the bills, her fingernails always self-manicured but never painted. Without losing count, she’d quiz me on

la charada

—a traditional system of numbers paired with symbols used for divination and placing bets. She’d call out a number at random, and I’d answer with the corresponding symbol she had me memorize:

número 36—bodega; número 8—tigre; número 46—chino

(which I always forgot);

número 17—luna

(my favorite one)

; número 93—revolución,

the reason why I was born in

número 44—España

instead of in

número 92—Cuba

. Everything in the world seemed to have a number, even me:

número 13—niño

.

In a composition book with penciled-in rows and columns, she’d tally her profits, down to the nickels and dimes I helped her wrap into paper rolls. Sometimes—if I begged long enough—she let me keep the leftover coins that weren’t enough to complete a new roll. It seemed like a fortune to me at age nine, enough to buy all the Bazooka bubble gum I wanted from the ice cream man once a week; even enough to buy TV time from my older brother, Caco, so I could watch old TV shows like

The Brady Bunch

instead of football. But every now and then I’d go broke paying him not to squeal on me, like the time he caught me coloring my fingernails with crayons. Eventually I’d earn the money back by making him sandwiches, cleaning up his side of our room, or getting paid off for not telling on him, like the time I found cuss words scribbled all over his history textbook—in ink! Still, it wasn’t much money for him; he constantly bragged that he made more on a Saturday mowing lawns than I did in a whole month “playing around” with Abuela. He didn’t need any of her “stupid” money, he claimed.

Once Abuela and I were done with our accounting, I followed her through the house as she stashed the money in her

guaquitas,

her code name for the hiding places she shared with only me. Ones, fives, and tens went into a manila envelope taped behind the toilet tank; twenties and fifties underneath a corner of the wall-to-wall carpeting in her bedroom. The coin rolls we hid in the pantry, buried in empty canisters of sugar and coffee. “In Cuba I had to hide my

pesos

from

la milicia

—those

hijos de puta

! That’s when I started making

guaquitas

. I even had to hide my underwear from them,” she’d claim. The pennies she tossed into an empty margarine tub she kept at the foot of her blessed San Lázaro statuette in her bedroom. Every Sunday morning she emptied the tub into a paper bag, and dropped the pennies into the poor box at St. Brendan’s before mass. “You have to give a little to get a little, that’s how it works,

mi’jo,

” she’d profess, making the sign of the cross.

But somehow Abuela always seemed to get a whole lot more than she gave. She was just

dichosa

—lucky, she alleged, though she helped her luck along most of the time. When my parents had wanted to move from New York City down to Miami, she “gave” them ten thousand dollars for a down payment on a new house with a terracotta roof and a lush lawn. The same house where we now lived, located in a Miami suburb named Westchester, pronounced

Güecheste

by the working-class exiles like us who had begun to settle there once they got on their feet. Abuela had also agreed she’d take care of my brother and me while my father and mother worked full-time at my

tío

Pipo’s bodega, named El Cocuyito—

The Little Firefly

. All Abuela wanted in exchange was for her and my

abuelo

to live with us rent-free—for life! My parents had agreed to the deal, and Abuela was sure to remind her daughter-in-law every time they got into a squabble over money matters: “

Gracias

to me and San Lázaro we have this

casita

and we don’t live frozen in that horrible

Nueva York

anymore.”