Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (48 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

New York is just too big, too complex to be covered by any one writer. At best he can only offer his little tribute to something he loves, but which is beyond him…. The finest short piece on New York in recent years wasdone by E. B. White. It is the tribute of a kindly, observant aficionado recording the immensely kaleidoscopic and other outward manifestations of the city rather than its subtleties, inner moods and deeper implications and meanings…. Most New York pieces, contemporary or prophetic,wallow in staggering statistics, like an up-to-date Baedeker guide. A big city lends itself peculiarly to exaggeration, distortion, superlatives and hyperbole…. We are told that there are more Neapolitans in Gothamthan in Ischia, more Hebrews than in Haifa, more Irish than in Connemara, more Monégasques than in Monaco, more Down-easters than in Mount Desert, more Lapps than in Lapland, more Swedes than in Gothenburg, more Scots than on Loch Lomond, more Eskimos than in the Aleutians and more French Canadians than on the Restigouche River. They give us

ad nauseum

the exact total of nickels and dimes deposited during the rush hour in the subways, and of quarters snatched by toll collectors at tunnels and bridges, of yards of spaghetti unfurled and red ink guzzled daily on Mulberry Street.

Not bad, eh? But let me try to make the case for Robert Moses on other than literary grounds. My first argument is that he accomplished much more good than harm. He built Riverside Park and Jones Beach and dozens of neighborhood playgrounds and swimming pools, added 20,000 acres to the city's parkland, and 40,000 acres to Long Island's parkland, built seven major bridges (the Triborough, the Throgs Neck, the Bronx-

Whitestone, the Henry Hudson, the Verrazano, the Cross-Bay, the Marine Parkway) and almost all the highways and parkways in Greater New York, 627 miles total, without which the city would have become completely immobilized and stagnant. The fact that Caro spent hundreds of pages diligently and judiciously chronicling the magnificent things Moses did matters little, partly because most people who summarize

The Power Broker

never actually read that massive work, and partly because the public loves contemplating Moses more as its vampire than as its benefactor.

My second argument is that Moses is unfairly held accountable for many questionable urban policies that were national, even global, at the time. It was not Moses who chose the automobile as the preferred mode of transportation in the twentieth century, or passed the federal highway construction act that unloosed billions of dollars for suburbanization, or decided that highways ought to be placed along the waterfront (that was done everywhere, alas), or decreed that public housing should be sited according to neighborhood racial patterns (that was standard governmental “wisdom” at the time), or mandated millions for slum clearance. He merely implemented those policies; yet somehow he has become their personification. Caro's perception is that because he carried out those policies so forcefully and skillfully, everyone else copied him. I would argue that those policies were going through, Moses or no Moses. What Moses did was to follow the flow of dollars, wherever it happened to be at the moment, and siphon off a sizable chunk, creating and maintaining control of his own revenue stream, for what he deemed the betterment of New York.

Even regarding his questionable policies, his record is sufficiently a mixture of good and bad that how we choose to evaluate Moses, case by case, depends largely on our initial predisposition for or against him. Yes, he placed highways on the river, cutting off the populace from waterfront access, but he also tucked them under beautifully in places (such as the Brooklyn Promenade, Carl Schurz Park, and the Battery). Did he fail to tuck them under throughout because he was evil, or because the budget did not permit more? Yes, he rammed through thousands of low-income public housing units that were grim, depressing, and monotonous; but the city, in its chronic housing shortage, would today be desperate without

them. Yes, he tricked Staten Island into letting the municipality use Fresh Kills as a garbage dump by claiming it would only be temporary; but as it happens, it served that function beautifully, and now that it is closed, New York faces a major waste-disposal crisis, costing the city a billion dollars a year. Yes, he engaged in slum clearance that cruelly displaced thousands of poor people; he replaced it with housing for the middle and upper class, but also with facilities that helped consolidate New York's status as world capital: the United Nations headquarters, Lincoln Center, the Coliseum, and the Fordham, Pratt, and Long Island University campuses. I have to say that cities are not obliged to maintain slums as slums, and when a market for higher-end uses exists, it may make fiscal sense to go for it, taking into consideration the greater good. Of course, you hope that in upgrading these neighborhoods, a commensurate effort is made to provide decent low-income housing elsewhere for those displaced—a hope often disabused. Moses often seemed cheerfully indifferent to the plight of those dislocated by his constructions. On the other hand, Moses built more public housing than anyone else did.

My third argument is that too much of the anti-Moses sentiment derives from his character (at least as it has come down to us from Caro), and that we are far too petty, too limited by our culture of resentment and political correctness, in assessing it.

The Power Broker

paints an indelible portrait of the man as an elitist, a racist, and a wannabe WASP patrician, an early champion of meritocracy whose later arrogance and intellectual contempt led to the autocratic refusal to listen to others, and (horrors!) a builder of highways who never drove a car himself. Some of these judgments seem the work of a hanging jury. We are told that, having failed as a politician because he lacked the common touch, he amassed uncommon power behind the scenes. Well, what is wrong with an able person seeking to accomplish things as an appointed official, if he cannot get elected to public office? Must we act naïvely shocked that, in a capitalist democracy, considerable clout may rest in the hands of non-elected individuals? Perhaps the time has also come to forgive Moses for roughly taking people by the arm when he wished to make a point. Of course the man was arrogant. He was the greatest city builder in history, as Caro himself acknowledges. He made Baron Haussmann look like a subcontractor.

A better title for Robert Moses' life story might have been

The Master Builder;

but by calling his huge study

The Power Broker,

Caro fixed a label on Moses that would throw him more into the company of Boss Tweed and Mayor Daley than of Daniel Burnham and Edwin Lutyens. Not that it didn't make good dramatic sense; by doing so, he could transform his biographical subject into a Shakespearean tragic protagonist, a Richard III or Macbeth, grasping for more and more power. Caro's argument that power is an addictive drug, or “the more you have it, the more you want,” rests on the unspoken assumption that power itself and the desire for it are intrinsically evil. To place that argument in context, we must remember that

The Power Broker

came out of a particular historical moment, dominated by Vietnam antiwar politics. The legacy of that moment—the lingering prejudice, or should I say intellectual consensus, against the exercise of power and the pursuit of glory—is so in tune with our age that it requires taking a step back to grasp just how peculiar it would have seemed to the ancient Greeks, say, or to the makers of the Italian Renaissance. While what motivated Moses, to Caro, was the sheer abstraction, Power, to my way of thinking it was the chance to use his gifts effectively, to accomplish his vision. For instance, when Moses took over the public housing authority, an unsympathetic observer could see this as a naked grab for more power: his need to control every facet of New York City's operation. But Moses himself, given his very justified confidence in his abilities as a builder of public works, and his awareness that no one else around was even remotely as capable, might have felt that if those units were going to get built, it would have to be by him.

Moses was also a pragmatic politician. He knew how the levers of society operated, and his dislike of planning critics and do-gooders rose largely from his sense that they did not. He defended the Metropolitan Life Insurance's building of Stuyvesant Town, even if it meant splitting off an uptown counterpart, Riverton, for blacks, because to turn down the offer would have, Moses felt, discouraged any private builders in the future from touching moderate-income housing in New York. Acknowledging in a letter that the Metropolitan Life's chairman, Fred Ecker Sr., was “hardboiled and conservative” and had surrounded himself with some “very poor advisors,” Moses went on to say: “The only constructive suggestion I can offer is to get Fred senior to take more Negro tenants at Stuyvesant and Cooper, get himself a

new

housing vice-president with more milk of

human kindness and less ice water in his veins, and keep abreast of the times….” Did Moses have racist tendencies? Very, very likely. But as we can see from this letter, it was not the entire story; being a pragmatist, he also understood that integration was a sign of the times.

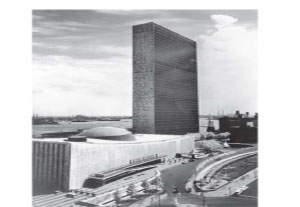

Another example of this pragmatic approach: Moses wanted to place the United Nations headquarters in Flushing Meadows, the old World's Fair site, where he thought the organization would have more room to grow than in Midtown Manhattan. But when the United Nations hierarchy, cool to the Flushing Meadows site, started leaning toward another city, Moses got on the phone and, with Nelson Rockefeller, helped broker the deal by which the Rockefeller family bought the East Forties property from William Zeckendorf and donated it to the city. For a man lambasted as rigid, Moses showed remarkable flexibility when it mattered. Not that his ability to compromise earned him any points with purists, but the secretary general of the UN, Trygve Lie, who favored a Manhattan site, certainly appreciated it.

In keeping with the Shakespearean tragedy scheme, Caro breaks down Robert Moses' life into discrete segments: Moses the Good, Moses the Bad, with 1954 being the fault line. When he built parks for kids and fought the Long Island barons to put a parkway through to the shore, so that the public could bathe at Jones Beach, he was a populist and a good guy. When he put a highway through a working-class quarter of the Bronx, he was an autocrat and a bad guy. This

All the King's Men

scenario of a fall from virtue distorts his basic unitary nature. He saw himself as consistently operating the same way, following the same broader regional vision.

Unarguably, the destruction of the city's fabric by the Cross-Bronx Expressway and other Moses highway projects was deplorable. But the dice seem unfairly loaded when Caro, recounting the Cross-Bronx Expressway saga, pits King Robert against the little people, such as Sam and Lillian Edelstein, and lo and behold, the reader chooses Sam and Lillian. The sad fact is that even when no highways went through those old Jewish working-class neighborhoods, they were doomed to change and wither, gone the way of the two-cent seltzer glass, the egg cream, the well-made knish, and all those other nostalgic memories. There is only so much you can blame on highway construction.

I might add that some of the worst sins for which he is held accountable are projects that never got made, such as the Lower Manhattan Expressway. Awful they undoubtedly would have been; but it seems topsyturvy to minimize all the wonderful deeds he did, while fixating on his unbuilt plans. We Lilliputians can no longer take the measure of Robert Moses. We have problems with great men in general. From my own, ant's, perspective, he was one of the greatest Americans of the twentieth century, a maker and a

macher

who changed the shape of our lives, on a par with Thomas Alva Edison and D. W. Griffith and W. E. B. Du Bois and Frank Lloyd Wright. I await the day when he gets his own postage stamp, or at least an avenue named after him in his beloved New York.

24 TUDOR CITY, THE UNITED NATIONS, AND THE UPPER EAST SIDE

A

T THE END OF

42

ND STREET

—

AFTER ALL THE BRIGHT LIGHTS AND NEON AND BACKSTAGE DRAMA WITH RUBY KEELER COMING TO THE RESCUE, AND RUNAWAYS turning tricks and sex shops and gamblers that earned it its raffish nickname, “the Deuce”—as far east as you can go without falling in the river, that notorious thoroughfare reforms and culminates in tranquil, respectable Tudor City and the United Nations, the hope of the world.

Tudor City consists of twelve buildings (with 3,000 apartments and 600 hotel rooms) extending from East 40th Street to East 43rd Street, between First and Second Avenues. It is a harmonious, serenely planned

private kingdom, like nothing else in Midtown, and I have always been intrigued by it, wishing I could live in so protected an environment right in the middle of the city, yet mistrusting its stage-set air of self-satisfaction.

Designed and built by the Fred C. French Company in 1925-32, it was begun in the boom years of the twenties, ran smack into the Great Depression, and continued on course during those dark days, finishing around the same time as the Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center. Fred C. French was a bold developer, responsible for the elegant skyscraper at 551 Fifth Avenue (with massive bronze doors, polychromed faience panels, and Ishtar-inspired Babylonianism) that today bears his name, and for Knickerbocker Village, the decent, moderate-income housing project in the Lower East Side, among other New York properties. His vision regarding Tudor City was to provide better living conditions for white-collar workers in the new office towers ascending around Grand Central Station. “Men could walk to work in the morning. Children could play in the community gardens, out in the open air,” French told

New Yorker

reporter Robert M. Coates in 1929. Influenced by the garden-city ideas of Patrick Geddes and Lewis Mumford, the Tudor City plan called for a ribbon of high-rise, high-density residential towers encircling a green open space. French assembled a five-acre parcel on Prospect Hill that had held some smaller brownstones and townhouses (a few of which still stand), but was otherwise sparsely populated, and built his three-sided fortress around a landscaped forecourt, open to the west.