Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (45 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

It's curious to compare the benign intentions of planners and the more crusty reality sixty years later. Not that it isn't still a wonderful park—or will be, when the underwater foundations have been repaired. So that derelict band shell really was a big deal once. Two thousand spectators! How many culture-loving, impecunious couples in the forties must have started out there on a first date? Rachmaninoff, Gershwin, Shakespeare, all for free. “Symphony, chamber music, opera and jazz in a small, neighborhood park. A little out of the way, possibly risky, but worth a wary try,” wrote the divine Kate Simon in her 1959 guidebook

New York Places and Pleasures,

about the East River Park Amphitheater. Was that cup-strewn slope with barbecue grills what the planners had in mind as a “gossip center”? If so, they were basically on target. But not even Robert Moses could have seen ahead to the shipworms.

POSTSCRIPT:

The East River Amphitheater, whose degraded condition I lamented, was miraculously repaired in a week by volunteer labor, working around the clock, for a television show about civic projects called “Challenge America.” The modest concrete band shell has a polished white exterior with blue tiles inside, and two enormous butterfly-wing thingies with strung wires (are these purely decorative, or do they have some acoustic function? If the former, I say get rid of them) extended from its front and back. The trowel job on the band shell looks clumsy and patchy, but this volunteer workmanship is preferable to the decades of bureaucratic delays that might have hindered a professional restoration, had it been bid and haggled over the usual way. The wooden benches are all new and nailed together shipshape, if splintery on the derriere. All in all, it is a fine precedent established for vigilante urbanism by communities that would take repair jobs into their own hands.

22 CON EDISONLAND: FROM ONE POWER PLANT TO ANOTHER

A

MONG THOSE OPERATIONS DRAWN TO THE EDGES OF MANHATTAN, WE MUST NOT OMIT THE ELECTRIC COMPANY, CONSOLIDATED EDISON, WHICH BUILT TWO LARGE power stations on this part of the East River: one at 14th Street and one a mile north, between 38th and 41st Streets. Power plants were originally sited on rivers because they burned coal, which was brought in by barge, and because they required huge amounts of water for cooling and other operations. Later they switched to burning oil, also barge-transported, and now are increasingly converting to gas while keeping oil as a backup. Although much of the demand for river water has been reduced by technology, the underutilized waterfront remains a tempting dumping ground for power plants. At present, nearly three-quarters of New York City's

electricity is generated by power plants along the East River (many located on the Queens side, in Astoria and Long Island City), which says something either about the lack of respect for, or the touching confidence in, this much-abused waterway. Con Edison, the sole producer of steam for New York City's hospitals and other public buildings, is a key player in the East River's future, one way or another.

It is the customary karma of large, monopolistic utility companies, such as Pacific Gas & Electric or Consolidated Edison, to go unloved. Rather than receiving gratitude from their customers, they seem to inspire mistrust bordering on hatred. Far be it from me to say whether this antipathy is justified, but it is one of the few things that truly unite the people of a metropolitan region. I know I am no different: a native New Yorker, I was raised to hate Con Edison. The blackouts, which we blame on Con Ed without hesitation, are an intrinsic part of New York folklore: anyone who lived through one can tell you where he or she was when the lights went out, and what happened for the next twenty-four hours.

It is hard to put a face on Con Edison; there remains something covert and conspiratorial about its vast, tentacular “power grid,” its seeming freedom from accountability, its annual importuning for rate increases, deserved or not, its militantly self-congratulatory corporate image (dig we must, for a growing new york! read the sign placed outside every street-cut for many years, since replaced by the zippy on it). The English travel writer Stephen Graham, in his 1927 book of nocturnal perambulations,

New York Nights,

found himself on the East River waterfront, “listening to the ceaseless Edison works. Oh, what is Edison contriving there, are they engines of death or of life?” Experience suggests both.

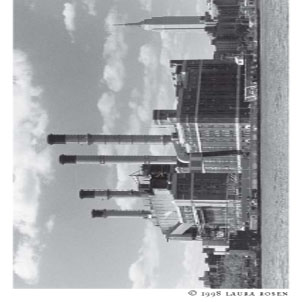

Four smokestacks painted sober gray and black, emitting white plumes of smoke, with exterior ladders running up their sides, are the most visible landmarks of the East 14th Street power plant. Closer up, you see two massive buildings with brick façades, much wider than tall, connected to each other by corrugated steel chutes, and sprouting stacks of coiled wire like the laboratory headdress of Elsa Lanchester in

The Bride of Frankenstein.

The buildings date from the height of America's distinguished industrial/mill architecture, but somehow these two gigantic brick boxes, holding inside them the power that feeds, or at least takes the edge

off, a metropolis's mad, sweet-tooth hunger for energy, are not distinguished, but simply mammoth.

The Con Edison power plant takes up more than three entire square blocks, from Avenue C to the river, and from East 14th Street to East 16th Street. It fills both sides of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Drive, so that East River walkers are reduced to a narrow concrete path adjacent to the highway, cars whizzing past, while, behind a fence, Con Edison's shacks, minimally used for unloading fuel tankers, continue to hog the riverside.

A gleaming, energy-efficient Con Edison office building of curved green glass, with white lattice roof, at East 16th Street and the FDR Drive, has been added to the utility park. Designed by Richard Dattner (who did the Riverbank State Park), it is as graceful as a MOMA design-shop fruit bowl placed beside a tractor. As you drive by, it gives off an impression of tranquil marine transparency, though, close up, you can't see a damn thing inside.

The plant on East 14th Street, a behemoth to begin with, is slated for considerable expansion, mostly because the Midtown station a mile north is being sold off to real estate developers. Con Edison, realizing it possessed the only large area left undeveloped in Manhattan, saw that the sale of this land near the United Nations would be lucrative enough to pay for the expansion of the downtown plant, with no loss of capacity, and at the same time reap the company a hefty profit. It was, as they say, a “win-win” situation, except perhaps for the poor, largely Latino residents in the Lower East Side who lived downwind from the East 14th Street works: the plant's emissions would impact on them more severely than on communities to the north. According to public health statistics, Puerto Ricans are especially susceptible to asthma; and a disproportionately high number of asthmatics already lived in the housing projects alongside the East 14th Street plant. The anticipated plant expansion would inevitably increase the emission of fine particulate matter (called PM 2.5, because the particles are 2.5 microns or less), which recent medical studies have linked to asthma, lung cancer, and heart disease.

The East River Environmental Coalition, a group of tenants and community organizations, appealed the expansion. This neighborhood group did not take issue with the validity of expanding the plant to meet the city's power needs; nor did it question Con Edison's assertion that

improved technologies would make the new power plant much cleaner and more efficient, reducing the level of most pollutants (excluding PM 2.5) emitted overall. The problem was that this state-of the-art plant was going to be tacked onto a dirty, antiquated plant—one of eighteen obsolete plants in New York State that had been “grandfathered” by legislative statute, meaning it did not have to abide by modern clean-air standards. Since its pollution problems arose from burning oil in addition to gas, and from using old equipment, the community board wanted Con Edison to upgrade (or, in current lingo, “repower”) the old plant to burn only gas, and to install new equipment. Eventually a settlement was reached, whereby Con Edison agreed to increase its use of natural gas in the old plant, and install a nozzle in a smokestack to reduce the impact of fine particulates, in return for approval of Con Edison's expansion. While this settlement was a victory for the community, the nozzle will not be installed for another five to ten years, nor will it then entirely alleviate the pollution caused by the expanded East 14th Street plants; and so the fight continues.

EVEN BEFORE CON EDISON had bracketed the area with its electric plants, power suppliers dominated this strip of Manhattan waterfront. “In the 1840s, a number of gas tanks were erected near the East River. Because of leaks in the tanks, a foul stench invaded the East Side between 14th and 23rd Streets. Who, but the poor and the disreputable, would live there? And so the city's notorious Gashouse District was born,” wrote Edward K. Spann in

The New Metropolis.

A neighborhood populated initially by poor Irish workers and, later, by equally indigent Italians, Germans, and Jews, it had become, by the post–Civil War period, “one of the most turbulent sections of the city, for the celebrated Gas House Gang was just coming into power, and was terrorizing a large area,” wrote Herbert Asbury in his juicy popular history,

The Gangs of New York.

“Scarcely a night passed in which gangsters did not loot houses and stores and fight among themselves in the streets and dives, and the police were powerless to stop them.”

That is, until the captain of the twenty-first precinct, Alexander S. “Clubber” Williams, introduced the reign of the nightstick. In 1871,

Asbury notes approvingly, Williams “organized a strong arm squad which patrolled the precinct and clubbed the thugs with or without provocation. The district was soon comparatively quiet, and remained so throughout Williams' administration.” (A less admiring portrait of Williams can be found in

The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens,

where he is shown presiding over the beating of Jewish strikers. Eventually the captain, grown rich beyond the reasonable expectation of a uniformed officer's salary, was hauled in during one of those periodic investigations of New York police corruption; his explanation, that he had made the money speculating in Japanese real estate, failed to wash.)

THE SLUMS AND DOCKS are long gone, replaced by that city-within-a-city, stretching from East 14th to East 23rd Street, the giant apartment complex known as Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village. (The latter is said to be a smidgen roomier and more upscale than the former, though I am never able to detect any of these advantages by comparison of their exteriors.) These middle-income,

*

rent-stabilized apartments were the city's gift to the war generation. Built by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, they are a reminder of a time when New York pioneered the construction of affordable housing in prime locations. When they debuted in 1947, Lewis Mumford deplored their totalitarian demeanor (now considerably softened by trees), and Dorothy Day, the saintly founder of the

Catholic Worker,

lamented in her autobiography that she and her fellow bohemians had to quit their cozy East River cold-water tenements, which were being razed to make way for that perfectly hideous Stuyvesant Town, and relocate to the still-neglected shores of Staten Island. One can sympathize with Mumford's and Day's opposition, or shudder at the thought of any more developments like Stuyvesant Town taking bites out of Manhattan's grid, while still acknowledging its utility and proven success. Though the complex still has little to recommend in the way of architectural charm, being merely a succession of brick high-rise barracks that stretch along the river district as far as the eye can see,

what is amazing is how well it has fulfilled its intended purpose (the provision of safe, decent, reasonably priced housing, and a lot of it), and how well the whole thing has become casually absorbed into the city's texture. It is enough to make one rethink one's notions about what makes for good urbanism.

*

Lately, some of Stuyvesant Town's apartments have been marketed as luxury rentals, undercutting the original intent.

ACROSS FROM STUYVESANT TOWN, and a few blocks north of the Con Edison plant, at the widest point of the East River, where a natural sandy cove has formed, a lovely new waterfront park has sprung up along the curved shoreline. Small—extending only from East 18th Street to East 21st Street at this point—Stuyvesant Cove Park packs in a botanical gar-den's worth of exuberant nature. Hundreds of yellow daffodils, grape hyacinths, and other wildflowers, and ten varieties of North American native trees (eastern poplar, ironwood, red mulberry, eastern red cedar, black cherry, butternut, common hackberry, swamp white oak, white oak, and blackberry viburnum) speckle the park with color. All the plantings—trees, perennial shrubs, grasses, and flowers—have been chosen because they are indigenous to the area, and because they tolerate sea spray and New York weather, survive in relative drought, and attract local and migrating birds. So far, cormorants, robins, gulls, ducks, geese, and swans have all been spotted around Stuyvesant Cove.