Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (4 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

By 1860 the port of New York was handling 52 percent of the nation's combined imports and exports. The New York Custom House was the principal source of revenue of the federal government. An army of customs inspectors, including Herman Melville, collected duties there that, according to Albion, “were enough to pay the whole running expenses of the national Government, except the interest on the debt.”

Part of this lucrative trade involved the Cotton Triangle, by which southern-grown cotton (in the first half of the nineteenth century,

America's most important export) passed through New York on its way to England and France. Though, geographically speaking, it made little sense to tack on several hundred miles' sea voyage by sending the cotton up north first, instead of shipping it directly from Charleston or New Orleans to Europe, New York's merchants and bankers were able to control the trade by financing the plantation owners' debts between crop payments. Some irate growers estimated that, when interest, commissions, insurance, and shipping were factored in, the northerners had skimmed forty cents of every dollar paid for southern cotton. New York's deep commercial connections with the South led elements of its mercantile class to feel less than enthusiastic about the Union cause; that, plus the Draft Riots, gave the city a slightly Copperhead (pro-Confederate) reputation. As during the American Revolution, the rest of the country mistrusted New York's patriotism. No matter: after 1865, the city profited by the defeat of the South, just as it had by the war.

In the peacetime era that followed, the most important change affecting the city's form was the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. Opening in 1883, this East River span, the “eighth wonder of the world,” lost Brooklyn its status as an independent city and led to its incorporation, in 1898, with Queens, Staten Island, and the Bronx, into modern New York, all subordinated to Manhattan, the nerve center. In short order, a cat's cradle of the Manhattan Bridge, the Williamsburg Bridge, and many equally workaday bridges and tunnels (no longer wonders of the world) connected Manhattan to the other boroughs and New Jersey.

In northern Manhattan, Hell Gate, a section of the East River from 90th to 100th Streets that proved notoriously difficult to navigate (a thousand ships ran aground there in an average year) was tamed by the dynamiting and removal of its most treacherous rocks, in a complicated demolition project that stretched from 1851 to the mid-1880s. At the northern tip, in an area bounded by the Spuyten Duyvil Creek and the Harlem River, the Harlem River Ship Canal was dug, splitting the Marble Hill neighborhood from Manhattan and joining it to the Bronx.

Although the increasing use of steamships had shifted some maritime traffic from the East River to the Hudson in the mid-1850s, the piers along the East River in Lower Manhattan remained the center of the city's shipping until the start of the twentieth century. After that, the action moved

to the Hudson River side, since ocean liners and tankers required a deeper channel and longer berths. In 1900, New York's shippers were still handling two-thirds of the nation's imports and one-third of its exports, a percentage that held throughout the massive increase in trade that occurred during World War I and into the early 1920s. Though the port began to lose market share by the mid-1930s, New York dock workers in 1950 were still unloading and dispatching nearly a third of all foreign cargo. They could still look back to the vital role the port of New York had played during World War II.

Twenty years later, Mannahatta's port, the one Walt Whitman had witnessed and sung (“hemm'd thick all around with sailships and steamships”), was dead. Supertankers and containerization required considerably more backspace (fifty acres per berth), such as could no longer be found in a dense metropolis. New York's maritime trade got shifted to New Jersey. With the concomitant loss of manufacturing, sweat-labor, for the most part, disappeared from the island.

Manhattan remained the world's financial capital, the nexus of global headquarters, a skyscraper magnet, and an endlessly self-celebrating concentration of media, culture, tourism, retail shopping, and restaurants. Still desirable, Manhattan retooled itself; its specialty became self-cannibalism, real estate. It now sold the image of itself. But Manhattan as solitary symbol has been overstressed, masking its interdependence on the larger region to which it belongs. The island is part of a 780-mile New York waterfront. To the north, Westchester, the suburbs, Albany; to the west, Newark, Arizona, and so on, as Saul Steinberg would have said (or drawn).

1 THE BATTERY

M

Y CLOSEST ESTIMATION OF THE BULBOUS V-POINT, THE MAGNETIC SOUTHERN TIP OF MANHATTAN ISLAND, IS THE STATEN ISLAND FERRY TERMINAL. It's a sunny winter day and, fortified by two cups of coffee and a poppy-seed bagel, I head to the terminal where one catches the boat to Staten Island.

For as long as I can remember, the scuzzy-looking terminal that was here until recently, abounding in pizza outlets, couldn't have been less impressive if it tried. It was to have been replaced long ago, first by a sober office tower designed by Kohn Pederson Fox, then by Venturi, Scott-Brown and Associates' playful terminal with a giant, iconic clock. But Staten Island politician Guy Molinari objected to having to stare at this whimsical timepiece, which he found insufficiently respectful of his oft-late-to-work commuters, and it was scrapped. Then architect Frederick

Schwartz got the assignment, and has remade the terminal into an attractive, if very modest, corrugated steel box with waterfront views from an elevated public deck wrapped in blue and aquamarine glass.

I enter Battery Park, or, as it is historically known, the Battery (so named because of its cannons, which originally protected the harbor). It remains one of the most congenial parts of New York, its tree-filled grounds decompressing you from the financial district. Along the promenade, with its new, ergonomically correct walnut benches and pink marble backrests, you have the luxury to gaze out at the bay, then back to the parade of foreign tourists, locals, teenage girls arm-in-arm. “My imagination is incapable of conceiving any thing of the kind more beautiful than the harbour of New York,” the visiting Frances Trollope wrote in 1832; “I doubt if ever the pencil of Turner could do it justice, bright and glorious as it rose before us … upon waves of liquid gold.” The unhurried, ceremonial pace of meanderers along the promenade suggests a Spanish

paseo—

in any case, not what one usually associates with New York. The fact that the Battery has functioned in this way for so long adds to its appeal.

“In the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and four,” wrote Washington Irving, “on a fine afternoon in the glowing month of September, I took my customary walk upon the Battery … where the gay apprentice sported his Sunday coat, and the laborious mechanic, relieved from his dirt and drudgery of the week, poured his weekly tale of love into the half averted ear of the sentimental chambermaid.” During the day the park seems always popular, partly because the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island ferries leave from it, partly because it has such juicy vistas. A well-worn recreation space, not even aspiring to the bucolic, the Battery works as a city park should, circulating people from the nearby skyscraper-thick streets to the water's edge.

Performers work the tourist crowds who are waiting for the next ferry. A West Indian with dreadlocks is playing “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town” on steel drums to one bunch, while an African contortionist in black shirt and red pants entertains another by twisting his legs around his neck and walking on his rump. Not an entirely appetizing sight, to my mind, though he releases his body-knot and comes up cheerfully for air,

declaring, “Okay, folks, one dollar. Japanese—two dollars.” A paterfamilias tells his children looking through coin-operated binoculars: “That's where Vito Corleone came over on a boat.”

I wander over to the circular Castle Garden, historically the site of a fort, summer tea garden, concert hall, immigrant processing center, and aquarium, and now the place to buy tickets to the Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island ferry. This moldy cinnamon doughnut, a spiffed-up ruin, has been rebuilt and remodeled so many times you would be hard pressed to feel any aura of the authentic emanating from its stones. But the gesture of retaining it is appreciated.

Originally built between 1808 and 1811, it was constructed about two hundred feet offshore in thirty feet of water, like a stable boat. This engineering feat was largely the achievement of Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Williams, who covered the fort in stone thick enough to withstand hostile naval bombardment, and added iron filings to the mortar that held the façade together, which made the walls more durable and adaptable to a watery environment. Williams, one of the first professional military engineers in America, also designed Castle Williams on nearby Governors Island. In all, four batteries were installed to defend the harbor, and may have in fact helped dissuade the British from attacking the city during the War of 1812. A wooden bridge connected Castle Clinton to the Battery in Manhattan; ultimately it was made redundant by landfill.

In 1824 the federal government gave the fort to the city, which turned it into Castle Garden, a celebrated entertainment hall, where “the Swedish Nightingale,” Jenny Lind, first sang on her American tour. In 1850, after the premiere of

La Sonnambula,

New York's indefatigable diarist, George Templeton Strong, wrote: “Everybody goes, and nob and snob, Fifth Avenue and Chatham Street, sit side by side fraternally on the hard benches. Perhaps there is hardly so attractive a summer theatre in the world as Castle Garden when so good a company is performing as we have here now. Ample room; cool sea breeze on the balcony, where one can sit and smoke and listen and look out at the bay studded with the lights of anchored vessels, and white sails gleaming.…”

In 1855, during a peak immigration period (more than 319,000 immigrants reached the New York port in 1854 alone), Castle Garden was converted

into a reception hall for the entering masses. Before this innovation, those who came over in steerage had been routinely fleeced by runners at the docks, who stole their luggage or steered the newcomers to outrageously overpriced boardinghouses. These runners and touts often spoke the same language as their confused countrymen, the better to exploit their trust. Entering at Castle Garden, however, the immigrant could take stock, receive honest advice, and make further transportation arrangements at normal rates. In William Dean Howells's fine novel

A Hazard of New Fortunes,

the Marches approve of “the excellent management of Castle Garden, which they penetrated for a moment's glimpse of the huge rotunda, where the emigrants first set foot on our continent.… No one appeared troubled or anxious; the officials had a conscientious civility; the government seemed to manage their welcome as well as a private company or corporation could have done.”

It is interesting to contrast this rosy picture with the testimony of one who actually went through the processing line, Abraham Cahan (in his classic immigrant novel,

The Rise of David Levinsky

): “We were ferried over to Castle Garden.… The harsh manner of the immigration officers was a grievous surprise to me. As contrasted with the officials of my despotic country, those of a republic had been portrayed in my mind as paragons of refinement and cordiality. My anticipations were rudely belied. ‘They are not a bit better than Cossacks,’ I remarked to Gitelson.… These unfriendly voices flavored all America with a spirit of icy inhospitality that sent a chill through my very soul.”

The immigrant station at Castle Garden was closed in 1890; two years later the much more famous one at Ellis Island opened. In 1900 Castle Garden reinvented itself as the city's aquarium, around which time the journalist John C. Van Dyke compared it to “a half-sunken gas tank.” Now Ellis Island beckons as the revered national landmark of immigration, while the rotunda-less, roofless Castle Garden operates as a sort of glorified tickets booth to that attraction.

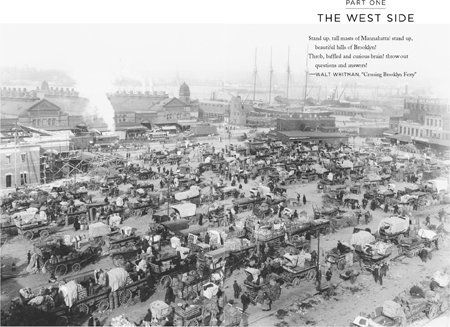

THIS AREA NEAR THE TIP of the island was once thick with piers and docks. There used to be some seventy-five piers between the Battery and 59th Street. Now there are only thirteen left. The New York system of narrow,

perpendicular “finger” piers that jutted out one after another, each holding a ship at a time, came about because the merchants could pack more vessels in that way, on an island with a fairly limited shoreline, than by having each boat tie up parallel to the land. The very advantage of New York's port, its sheltered harbors and deep waters, where any wooden pier would do to tie up at, deterred the city fathers from the large capital investments made by less geographically fortunate ports, such as Liverpool, which built majestic, palatial stone piers to hold off the fierce, crashing ocean waves. A slapdash setup (“the miserable wharves, and slipshod, shambling piers of New York,” Herman Melville wrote in his 1849 novel

Redburn

) was also justified at the time by the argument that ships kept getting wider and longer; thus it made little sense to “commit” to an expensive, heavy pier that would only have to be changed again in several years.