Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (2 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

T

HIS BOOK BEGAN AS AN ATTEMPT TO WRITE A SHORT, LIGHTHEARTED BOOK ABOUT WANDERING THE WATERY PERIMETER OF MANHATTAN. I HAVE LONG BEEN FASCINATED with walking-around literature, and everything about New York City. I thought I would write down whatever I was thinking and seeing in the course of my walk, including any encounters or adventures I might have. It was a quaint, likable idea, a sort of modern-day version of Robert Louis Stevenson's walks through France and England. But the first problem I encountered was that I could not pretend to be a tourist in my native city, discovering it with fresh wonder; I utterly lacked what the anthropologists call “culture shock.” Moreover, I was no longer a young man, for whom any city walk could release buckets of lyrical verbiage; I had exhausted those sorts of poems and urban sketches earlier, for the

most part. If I were to write about New York City now, it would have to be with the more reserved, critical perspective of a lifetime's accumulated uncertainties.

And I could not simply “meditate” (that last refuge of lazy belletrists such as myself ) on what I saw, I would actually have to

know

something about the waterfront: its past, its economic importance, its ecological concerns and development constraints. Which raised the second problem, my ignorance. I've always had a generalist's smattering of background information, but that's a far cry from true understanding. So I started to read as well as walk. The more I researched, the more I saw that the evolving waterfront was the key to New York's destiny, as it is to many former port cities globally.

The advent of containerized shipping, with its demands for acres and acres of backspace to load, unload, store, and truck the containers, has meant that, over the last forty years, in city after city around the world, the port functions have had to be moved, sometimes seaward, inland, or upstream, to rural or suburban areas where there was more available cheap land. This severing of the age-old connection between city and port is having profound cultural and economic effects, which we may not fully grasp for some time. At the moment, all we know is that cities all over the map are faced with empty harbors, and lots of underutilized waterfront property.

Today, in my native New York City, the waterfront has become the great contested space. Newspapers regularly carry announcements of some plan for a stadium, recycling plant, sound stage, wetland, park, marina, ferry, electrical generator, or museum, that is then fought over by the local community board, developers, and municipal and state governments. Over the last few decades, New York, like Washington Irving's Rip van Winkle, always seems to be reawakening from long slumber to discover it possesses… a shoreline! “The new urban frontier” is what a 1980s Parks Council report called the city's waterfront, inviting, it would seem, the brash, gold-rush behavior often associated with American frontiers.

Why is it, then, that developing the waterfront continues to have a forced, reluctant quality, as if New Yorkers were trying to talk themselves into root canal? Are there unconscious resistances at work, which may need to be examined?

There is, first of all, this particular city's historic habit of turning inland. It has often been remarked that, unlike most great cities on water, which tease and flirt with their liquid edges in a thousand subtle, sensuous ways, New York has failed to maximize its aqueous setting. This underutilization of the waterfront is mentioned as a curious negligence, as if it just happened to have slipped the locals' minds. Actually, the main reason why this shoreline resource remained so long “untapped” is that it had been already allocated for maritime and industrial uses. These functions may not have provided the best urban design, public space, or environmental protection, but they were a huge economic motor driving the region's economy. So the present opportunity, bear in mind, stems from a vacuum left by the port's demise and relocation elsewhere.

Shabby and makeshift though much of the old working port may have been, its vitality issued from the way that purpose had dictated its construction. As more boats came in, as more docks were needed, they got built; warehouses were erected to hold the goods loaded off the ships; customs offices, shipping agents, chandlers and ropemakers, retailers of barrels and packing cases, brothels and seamen's churches, taverns and boardinghouses and union halls, all sprang up around the docks. Nothing can replace the beautiful, urgent logic of felt need. When it is met in an ad-hoc, accreted manner, urbanists speak glowingly of “organic” city growth. I put “organic” in quotation marks because I don't believe any large human endeavor such as constructing a metropolis can ever be spontaneous or unplanned—the term “organic” tends to cloak a good deal of maneuvering by powerful special interests, such as the shipping lobby; so let us say, then, “additive” or “incremental” instead of “organic,” to connote the lot-by-lot assemblage of a classic New York streetscape.

Now that the old port is gone, and the river's edge sits dormant, waterfront recycling makes a certain sense (“We've got all this valuable riverview property close to the center of town, we got a populace starved for public access to water, we might as well do something about it”). But that reasoning still has a slightly abstract air, lacking as it does the keen urgency that commandeered the old port's growth. And that lack produces an ache—call it the ache of the arbitrary: we wish we could feel driven to redevelop the waterfront because the city's very life depended on it. Instead we are faced with more tepid drives: the profit motive of realestate

developers (but they can make money elsewhere), and the altruistic motive of community advocates for parks and a cleaner, greener environment. Yes, each of those interest groups may be passionately committed to their agendas; but there is not the same imperative to act promptly as in the past.

Some of the resistance is historical: Broadway and Central Park together had helped establish Midtown as the city's fashionable center, while its waterfront districts were associated with bad smells and low rents. All recent efforts to draw maximally upscale residential development to the water's edge have had to overcome that history, and the hierarchical superiority of the center to the periphery. In other words, however desirable a river view may be, for the wealthiest clientele it can never replace proximity to Central Park or Bergdorf 's.

The sense of urgency is further vitiated by the incredibly long time that waterfront development projects seem to require, from inception to completion. Manhattan is now entering its fifth decade of waterfront “rebirth” (the original plans for Battery Park City were drawn up in 1961). While New Yorkers might self-pityingly blame local corruption, the truth is it is a slow process everywhere. Waterfront projects are typically delayed five to ten years just by the complexities of achieving political consensus and government approvals; then there are the problems of site assembly, site clearance, environmental remediation, new infrastructure, and often millions in cost overruns. Hence, we who are living through the great leap forward of waterfront revitalization should cultivate patience, perspective, and reincarnation skills, because we may not see the changes in our lifetime.

There is also a clash between the waterfront zone—a separate corridor with redevelopment issues unto itself—and the neighborhoods it traverses. Traditionally the working waterfront has had a separate visual character, a more rough-hewn quality than the inland areas. The riverside highways that have come to rim the island compound the problem of getting to the Manhattan waterfront. These perimeter highways ignore the grid, or, rather, intentionally oppose a powerful counter to them, a moat between the everyday city and the water. They have also introduced disjunctions in scale, which can never be more than awkwardly reconciled, between highways meant for thousands of speeding cars and the buildings abutting them. In theological terms, the West Side Highway and the

Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive constitute the Original Sin of Manhattan planning. We may repent, we may patch, but—short of burying or lidding these highways, which would be very, very costly—we can never regain our wholeness.

NEW YORK

'

S WATERFRONT has undergone a three-stage revaluation, from a working port, to an abandoned, seedy no-man's-land, to a highly desirable zone of parks plus upscale retail/residential, each new metamorphosis only incompletely shedding the earlier associations. We may think of Manhattan's shoreline as a golden opportunity, a tabula rasa for leisure and luxury development, but the ghosts of stevedores, street urchins, and shanghaied sailors still haunt the milieu. Physically, no area of New York City has changed as dramatically as the shoreline, thanks to natural processes, landfill, dredging, and other interventions. Only by considering the waterfront's past can we account for New York's current, perplexing relationship to its future.

I WOULD HAVE BEEN HAPPY to write a traditional history of New York's waterfront, had I a historian's training, twenty years' leisure, and an independent income, but this book is not it. It is, however, saturated with history. Everywhere I walked on the waterfront, I saw the present as a layered accumulation of older narratives. I tried to read the city like a text. One textual layer was the past, going back to, well, the Ice Age; another layer was the present—whatever or whoever was popping up in my view at the moment; another layer contained the built environment, that is to say the architecture or piers or parks currently along the shore; another layer still was my personal history, the memories thrown up by visiting this or that spot; yet another layer consisted of the cultural record—the literature or films or other artwork that threw a reflecting light on the matter at hand; and finally there was the invisible or imagined layer—what I thought

should

be on the waterfront but wasn't. At any one point I would give myself the freedom to be drawn to this or that layer, in combination or alone.

Throughout, I walked the waterfront. The notion of one marathon circumambulation

quickly gave way to a multitude of smaller walks in all seasons: when my legs got tired, or my head grew dizzy from absorbing impressions, I stopped for the day. In the end, I not only explored by foot the island's perimeter (including several stretches that seemed dicey or were closed to the public), I often revisited an area, reconnoitering the same ground until it spoke to me. Sometimes I brought along friends, who lightened my quest for the waterfront's soul. I made long-overdue pilgrimages to the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, the United Nations, and Gracie Mansion, all of which, as a native New Yorker, I had previously ignored. I also interviewed experts, and sampled the mixed pleasures of community board meetings and public hearings.

All along, I kept coming up against certain underlying questions: What is our capacity for city-making at this historical juncture? How did we formerly build cities with such casual conviction, and can we still come up with bold, integrated visions and ambitious works? What is the changing meaning of public space? How to resolve the antiurban bias in our national character with the need to sustain a vital city environment? Or reconcile New York's past as a port/manufacturing center, with the new model of a postindustrial city given over to information processing and consumerism?

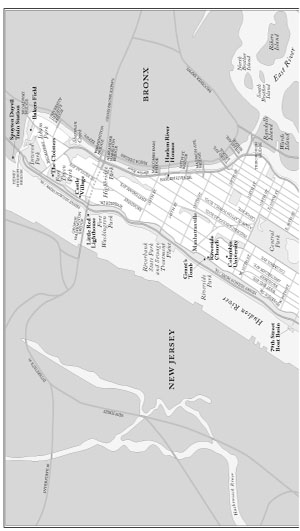

No one book can tackle all such questions fully, much less respond to every inch of the waterfront, past and present. Gaps are unavoidable. I have had to restrict my scope to Manhattan, instead of covering all five boroughs and the extended New York harbor. Even so, I have had to be selective: what I've done is to look for representative stories or themes—to take soundings along the edge. In Part One, I make my way geographically up the West Side, from the bottom of the island to the top; in Part Two, I return to the island's southern tip, this time proceeding northward along the East Side's coast. The structure is as follows: I alternate accounts of my walks with digressions, which I call “excursuses,” on individual topics that seemed to me characteristic of a larger pattern. These excursuses have been corralled into separate essays because they seemed to me too complex to deal with as throwaway insights along a walk.

The result is a mixture of history, guidebook, architectural critique, reportage, personal memoir, literary criticism, nature writing, reverie, and who knows what else. Consider it a catchment of my waterfront thoughts.

Writing about the Manhattan waterfront is like writing on water.

You've only to characterize some physical part of the cityscape or deliver an opinion on a current situation, for the reality to change next week. I am well aware that in years to come, much of what I have written in this book will sound dated, superseded as it will inevitably be by unforeseen circumstances. What can you do? I have described the waterfront I saw before me.

*

The very fact that the waterfront remains so elusive and mutable has ultimately ensured its fascination for me: it has become the ever-enigmatic, alien fusion of presence and absence. Its meanings have needed to be excavated, its poetry unpacked. I hesitate to use that word “obsession,” but, in my own limited way, I have become obsessed with the waterfront. I think about it when I drop off to sleep, and when I wake up; it forms a wavy limit hovering over my subconscious; I am quick to pick up any reference to it in periodicals, films, or overheard conversations. I have acquired the cultist's touchiness.

*

Futurists predict big changes for the Manhattan waterfront. Global warming may further melt the ice cap, causing respiratory ailments and power brownouts. Starting in 2080, the raised sea levels may bring on huge storms that will batter the New York coastline every three or four years. By that time I will seriously have to consider doing a revised edition of this book.