War: What is it good for? (28 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

And so it turned out. By lunchtime, the English had killed ten thousand French for the loss of just twenty-nine of their own. French corpses, the chroniclers said, were stacked so high that men could not climb across them, with many a knight ennobled just that morning drowning in gore beneath a pile of the dead.

Yet much as it pains someone who grew up in England to admit it, the story that the good man should really be teaching his son about 1415 involves an entirely different band of brothers, fighting under a fierce Mediterranean sun rather than a steady French drizzle. That summer, a flotilla had left Lisbon, crossed the narrow waters to Morocco, and stormed the city of Ceuta. This battle was even more one-sided than Agincourt, leaving several thousand Africans dead as against only eight Portuguese, but this was not what made it special. Ceuta's importance, only recognized long afterward, was that this was the first time since the Roman Empire that European productive war had gone intercontinental.

European warriors had crossed the seas beforeâVikings to America, crusaders to the Holy Landâbut they had always gone to get away from their masters and carve out their own little kingdoms, independent of any larger Leviathan. At Ceuta, by contrast, Portugal's King John was

expanding Lisbon's rule into Africa. It was a small beginning, but over the next five hundred years Europeans would blast their way out of the cycle of productive and counterproductive wars to take three-quarters of the planet under their rule. Europeans were about to become the happy few.

Footnotes

1

The opening scenes of the 2000 film

Gladiator

re-create in stirring style the last great battle of the Marcomannic War, in

A.D.

180.

4

THE FIVE HUNDRED YEARS' WAR: EUROPE (ALMOST) CONQUERS THE WORLD, 1415â1914

The Men Who Would Be Kings

One Saturday night in the 1880sâ“a pitchy black night, as stifling as a June night can be,” says the storytellerâtwo Englishmen, Daniel Dravot and Peachey Carnehan, stride into a newspaper office in northern India. “The less said about our professions the better,” they announce; the only thing they care about tonight is how to get to Kafiristan (

Figure 4.1

).

Figure 4.1. Locations in Asia mentioned in this chapter

“By my reckoning,” says Dravot, “it's the top right-hand corner of Afghanistan, not more than three hundred miles from Peshawar. They have two-and-thirty heathen idols there, and we'll be the thirty-third and fourth ⦠And that's all we know, except that no one has gone there, and they fight; and in any place where they fight, a man who knows how to drill men can always be a King.”

Disguised as a deranged Muslim priest and his servant, with twenty Martini-Henry rifles hidden on the backs of two camels, Dravot and Carnehan drag themselves through sandstorms and blizzards until, in a big level valley crusted with snow, they spy two bands of men shooting it out with bows and arrows. “âThis is the beginning of the business,'” says Dravot, “and with that he fires two rifles at the twenty men, and drops one of them at two hundred yards from the rock where he was sitting. The other men began to run, but Carnehan and Dravot sits on the [ammunition] boxes picking them off at all ranges, up and down the valley.”

The survivors cower behind what cover they can find, but Dravot “walks over and kicks them, and then he lifts them up and shakes hands all round

to make them friendly like. He calls them and gives them the boxes to carry, and waves his hand for all the world as though he was King already.”

Dravot now sets about becoming a stationary bandit. First, “he and Carnehan takes the big boss of each village by the arm and walks them down into the valley, and shows them how to scratch a line with a spear right down the valley, and gives each a sod of turf from both sides of the line.” Then, rounding up the villagers, “Dravot saysââGo and dig the land, and be fruitful and multiply,' which they did.” Next, “Dravot leads the priest of each village up to the idol, and says he must sit there and judge the people, and if anything goes wrong he is to be shot.” Finally, “he and Carnehan picks out twenty good men and shows them how to click off a rifle, and form fours, and advance in line, and they was very pleased to do so.” In each village Carnehan and Dravot come to, “the Army explains that unless the people wants to be killed they had better not shoot their little matchlocks”; and soon enough, they have pacified Kafiristan, and Dravot is planning to present it to Queen Victoria.

Rudyard Kipling made up Dravot, Carnehan, Kafiristan, and its two-and-thirty heathen idols in 1888 for his short story “The Man Who Would Be King,” to titillate readers hungry for ripping yarns of imperial derring-do. But what made the tale such a hit, and still worth reading today, was that the nineteenth century's truth was really no stranger than Kipling's fiction.

Take, for instance, James Brooke, a wild young man who joined the British East India Company's army at sixteen. After taking a bad wound fighting in Burma, he bought a ship, loaded it with cannons, and sailed it to Borneo in 1838. Once there, he helped the sultan of Brunei put down a rebellion. The grateful ruler made Brooke his governor in Sarawak Province, and by 1841 Brooke had parlayed this into his own kingdom. His descendantsâthe White Rajahsâruled for three generations, finally handing Sarawak to the British government in 1946 in return for a (very) generous pension. To this day, the best-known pub in Sarawakâthe Royalistâis named after Brooke's ship.

It was the hope of emulating Brooke, Kipling had his heroes say, that drew them to Kafiristan, “the [last] place now in the world that two strong men can Sar-a-whack.” But they were not the first to try Sar-a-whacking in central Asia. In 1838, the very year that Brooke arrived in Brunei, an American adventurer named Josiah Harlan had already had a go. After losing in love, Harlan had signed up as a surgeon with the British East India Company and served in the same Burmese War as Brooke. When this ended, he drifted across India, eventually talking the maharaja of Lahore into giving him two provinces to govern. From there Harlan led his own army into Afghanistan to depose the prince of Ghor, a notorious slave trader. Overawed by Harlan's disciplined troops, the prince of Ghor offered him a deal: he would give Harlan his throne, so long as Harlan kept him on as his vizier.

Harlan grabbed the chance and raised the Stars and Stripes in the mountains of central Asia. But his monarchical tenure turned out to be as short as Dravot's in Kafiristan. Within weeks of his elevation to royalty, Britain occupied Afghanistan and threw the new-made prince out. Returning to the United States, Harlan almost persuaded Jefferson Davis (then secretary of war) to send him back to Afghanistan to buy camels for the army; once there, Harlan hoped, he could renew his tenure as prince of Ghor. When this fell through, he tried importing Afghan grapes into America and then raised a regiment for the Union in the Civil War, but an ugly court-martial cut this career short too. He died in San Francisco in 1871.

Men like Brooke, Harlan, Dravot, and Carnehan would have been unimaginable in any age before the nineteenth century, but by that time the globe had changed out of all recognition. Between the Portuguese capture of Ceuta in 1415 and the era of “The Man Who Would Be King,” Europeans waged a Five Hundred Years' War on the rest of the world.

The Five Hundred Years' War was as ugly as any, full of trails of tears

and wastelands. It was fiercely denounced by modern-day Calgacuses on every continent, but it had its Ciceros too, who constantly drove home one big point: that this was the most productive war in history. By 1914, Europeans and their colonists ruled 84 percent of the land and 100 percent of the sea. In their imperial heartlands, around the shores of the North Atlantic, rates of violent death had fallen lower than ever before and standards of living had risen higher. As always, the defeated fared less well than the victors, and in many places colonial conquest had devastating consequences. But once again, when we step back from the details to look at the larger picture, a broad pattern emerges. On the whole, the conquerors did suppress local wars, banditry, and private use of deadly force, and began making their subjects' lives safer and richer. Productive war carried on working its perverse magic, but this time on a global scale.

Top Guns

What carried Europeans from Ceuta to Kafiristan was a new revolution in military affairs, fueled by two great inventions. Neither invention, though, was made in Europe.

The first invention was the gun. I mentioned in the previous chapter that Chinese chemists had been experimenting with low-grade gunpowder since the ninth century, making fireworks and incendiaries. In the twelfth or thirteenth century, some now-anonymous tinkerer worked out how to add saltpeter to make real gunpowder. Instead of burning, this would explode when set alight, and if packed into a sufficiently strong chamber, it could blast a ball or arrow out of a tube fast enough to kill someone.

Our first sighting of a true gun may be in the unlikely setting of a Buddhist shrine near Chongqing, China's fastest-growing city. Sometime around 1150, worshippers decorated this sanctuary by carving figures into the cave walls. It is all very conventional stuff, showing lines of demons standing on banks of clouds, and in another conventional touch the sculptor gave several of the demons weapons. One has a bow, another an ax, another still a halberd, and four have swords. But one holds what looks for all the world like a crude cannon, spitting out a little cannonball in a blast of smoke and flame.

This carving is controversial. Some historians think it proves that twelfth-century Chinese armies used guns; others, that it shows that guns existed but were so rare that the sculptor had never seen one (if you hold a metal bombard the way the carved demon is doing, they point out, it will

fry the skin off your palms); others still, that the demon is actually holding a musical instrument and that guns had not yet been invented. But however we come down on this issue, no one can dispute that guns were in use a century or so later, because archaeologists have found oneâa simple, foot-long bronze tube buried near a battlefield in Manchuria no later than 1288 (

Figure 4.2

).

Figure 4.2. The start of something big: the oldest surviving genuine gun, abandoned on a Manchurian battlefield in 1288

The 1288 gun would have been unpredictable, painfully slow to load, and wildly inaccurate, but bigger, better versions were soon in use. They were particularly popular in southern China, where much of the Yangzi Valley was in open rebellion against the country's Mongol rulers by the 1330s. Innovations came thick and fast, and within a decade or two the rebels had learned how to get the best out of the newfangled weapons. The first trick was to deploy them in large numbers (by 1350 the rebel state of Wu had turned out hundreds of cast-iron cannons, dozens of which survive); the second, to adopt combined-arms tactics. On the eve of his decisive battle against the Mongols, fought on Lake Boyang in 1363, the rebel leader Zhu Yuanzhang laid out the correct methods for his captains. “When

you approach the enemy ships,” he ordered, “first fire the firearms, then the bows and crossbows, and when you reach their ships, then attack them with hand-to-hand weapons.” Zhu's men did what he said, and five years later he became the first emperor of the Ming dynasty.

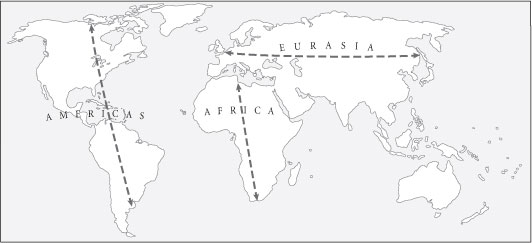

People on the receiving end of new weapons regularly copy them, and guns were no exception. Koreans had guns in their fortresses by 1356. It took another century for firearms to make their way around the Himalayas to India, but they were definitely used at the siege of Mandalgarh in 1456. By 1500, bronze cannons were being cast in Burma and Siam, and after a delay (caused, perhaps, by Korean officials' efforts to keep firearms from them) Japanese too took up the gun in 1542.

The most surprising story, though, is the gun's rapid success in distant Europe. In 1326âless than forty years after the first definite example of a Chinese gun, and thirty years

before

the first definite Korean caseâtwo officials in Florence, five thousand miles to the west, were already being ordered to obtain guns and ammunition (

Figure 4.3

). The next year, an illustrator in Oxford painted a picture of a small cannon in a manuscript. No invention had ever spread so quickly.

Figure 4.3. Locations in Europe mentioned in this chapter (the borders of the Ottoman Empire are those of

A.D.

1500)