Viper Wine (11 page)

Authors: Hermione Eyre

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary, #Genre Fiction, #Historical, #Mashups, #Contemporary Fiction, #Literary, #Historical Fiction

‘What does “as above, so below” mean?’ said young Kenelm.

‘Perhaps it means that we are a looking-glass version of the heavens. Perhaps it means that everything operates according to opposites. But there’s beauty of it. It can mean so many things according to your imagination. It is a precept which you have in mind to guide you as you do your alchemy. Do you be paying attention?’

‘Yus.’

‘We believe in the

anima mundi.

Everything is ensouled – whether it is the wind or the trees, which are obviously soulful, or something like a jewel or a clock, which ticks or sparkles, and is guided by its own stars.’

Standing by the armillary sphere, which was at his eyes’ height, young Kenelm was gravely tapping it with his finger so the world turned, and turned, and turned. He had an impatient facility for the mechanism that impressed and disquieted his father.

Sir Kenelm got up, standing in front of his limbecks and retorts. ‘Here,’ he announced, ‘are the rudiments of the process by which, eventually, base metals may be turned to gold. First . . .

‘Calcination.’ He rapped the furnace.

‘Solution.’ Ping! He flicked the glass.

‘Separation.’ Shh. He slid a finger down the conical flask.

‘Conjunction.’ He bent on one knee as if to pray.

‘Mortification.’ He pointed sternly to the fire-pan.

‘Putrefaction.’ Rattle! He shook the slop bucket.

‘Sublimation.’ He waved the fingers on one hand.

‘Libation,’ He blew bubbles from his wet lips.

‘Exaltation.’ He held a bowl up ceremoniously.

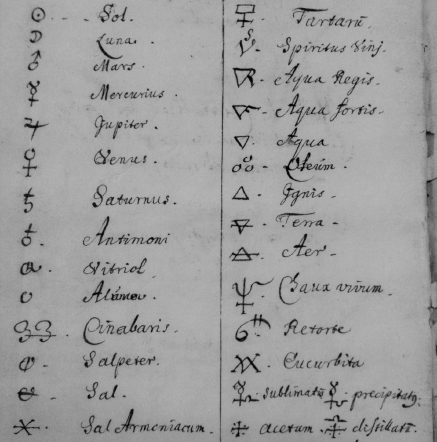

From the alchemical notebook of Sir Kenelm Digby

‘Some stages take a long time: others are swift. We practise them like games of the mind. Each has a hundred different possible outcomes, depending on the conditions, lunar and sublunar.’

Kenelm looked at Kenelm. He hoped he had not gone too far for one so young. The boy’s mouth was moving; he wanted to speak.

‘It reminds me very much of the brewing of ale that Mistress Elizabeth does down in the barn.’

Kenelm’s tufty yellow eyebrows rose very far up, as far as young Kenelm had ever seen them rise. He started putting away his apparatus quietly, humming to himself. ‘Well, sir, indeed. What did I say to you? As below, so above.’

I S

AW

E

TERNITY THE

O

THER

N

IGHT

LATE AT NIGHT,

while the household slept, Sir Kenelm was in his study, performing stealthy lucubrations. He was agitating quicksilver in a cork-sealed bolts-head, squinting as he followed the half-scrawled recipe, a loose page from his grimoire, a book in many languages, codes, formulae and Hebraic scripts, written in various hands, inks and fonts. The medicine he was preparing was a matter of urgency, since they must depart the next morning, but young Kenelm needed to be treated first, for it had been discovered that he had a slight but bothersome indisposition. In a word, worms.

Venetia recalled that a medal of St Anne should be hung around the boy’s neck, although she could not find one and used St Christopher instead. Kenelm thought it was worth also following his private recipe. The village remedy of rosemary water he did not deem effective. He found this far superior recipe in his book:

‘For worms in children, take 1 1/2 dram of the best running Mercury, put it into a bolts-head, spit fasting spittle upon it (from a wholesome mouth) and shake well. Then pour off the Spittle from it, and wash the Mercury clean with hot milk several times. Then allow the child this Mercury in a spoon with little warm milk upon it. Do this twice or thrice, intermitting two or three days between every dose.’

Kenelm Digby,

Chemical Secrets and Experiments

, 1668

Kenelm spat into the quicksilver, fancying he tasted its vapour, which was tart like blood. As he sat waiting for the milk to warm in the pan, he gazed into the shew-stone of the quicksilver and saw the distorted visage of his old tutor, Thomas Allen. He was wearing his gown and cap, and struggling to carry a great pile of papers, books and the wax discs that recorded his talks with angels, as well as a big heavy contraption with buttons marked with every letter in the alphabet, and slim mirrors, round in shape, marked Digital Versatile Disc. There was too much for Allen to carry and the pile was tumbling from his hands. Kenelm blinked and realised that he was only dozing and had been wakened by his own recipe slipping to the floor. He must go and see the old man in Oxford, before it was too late. Thomas Allen was eighty-nine.

Kenelm washed, and washed again the skittish silver liquid, then let it plop into a hornspoon. He could still see the face of Allen in the mercury, grimacing and distorting as the mercury spooled downwards and splashed into distinct globules, so there was a tiny Thomas Allen visible in each blob, and all of them were pulling different expressions.

Kenelm had proposed Allen as a member of the Invisible College, but the younger members rejected him because they feared the slur of sorcery. ‘We want no magi, no conjurations here,’ said young Pritchett. ‘He has the finest collection of mathematical books I have ever seen,’ said Sir Kenelm. ‘Do you believe the tittle-tattle that spirits thronged behind him on the college stairs like bees? Would you be like the maids of Sir John Scudamore’s household, afrit of a ticking box?’

Thomas Allen was a guest of Scudamore when the maids there threw away his watch, which they judged a mechanical familiar. As they were cleaning his room they heard a ticking, emanating from a little black box that must be the devil, and so, without touching it with their hands but using their pinnies or dishclouts, they threw it out of the window to drown the devil in the moat below. Luckily it caught by its string upon an elder bush and so Thomas Allen’s watch was rescued.

Sir Kenelm feared that the quick young Invisibles, with their hydraulics and botanical studies, were not schooled in Hermetic wisdom, so he filled in the basics airily for them: ‘Everything which is made is numbered in the mind of God. If the numbers that describe a toad were to be forgotten and fall from the mind of God then no toads should exist. Thomas Allen knows this mystical dimension of numbers, their mathesis . . .’

Kenelm said this speech, or something like it, to the company. But they stuck firm and would not have Thomas Allen, ‘nor the ghost of John Dee neither’, said Sir Cheney Culpeper, and the Invisibles tapped their quills on the table in agreement.

‘It is not that we believe Master Allen to be a conjuror,’ said another of the beardless wonders to him privately afterwards. ‘We do not. But the public tongue says he is, and therefore we put ourselves at risk if we take him into our ranks. We could be persecuted by the mob and our laboratories destroyed, as Dr Dee’s were at Mortlake. Or our patrons could withdraw their monies, or our designs could lose their warrants. It is because we are Prudent that we do not welcome him, not because we are Superstitious.’

Against everything, Digby took some pertinent volumes the Invisibles had in circulation, and sent them to Allen at Oxford. They returned two months later, pages somewhat dirtied and stuck together with soup, spindly incy-wee writing covering the margins. The old man’s scrawl seemed to wheeze, rising and falling, illegible even to Digby’s eye, once so familiar with his hand. The words he could read were indifferent to the purpose.

He was seized with an urge to go to Oxford almost at once to visit Allen, but he also knew that now was his time to be in London, his brief chance to shine while his naval exploits were news. He knew, from astrology, rhetoric and every noble discipline, that nothing could be achieved except if its timing were propitious. The stars must be in alignment before any new undertaking.

For example, the space-probes

Voyager 1

and

2

could not depart before the planets were in perfect order. Once every 175 years they fell into such orbits that their gravitational pull eased the flight of those great data-gathering insects so they glided effortlessly through the heliosphere. The

Voyagers

could have been launched in 1627, but no, Sir Kenelm was dozy; he was unprepared. In 1977 when the alignment came again, the

Voyagers

would surf the sky-tide.

An oak clawed at the laboratory window, and Kenelm rose and looked out over the blue expanse of grass, down to his obelisk, which was emitting a flashing halo of pale light. Circular rays were given off by every object, as the Alchemists knew. Time itself was circular, which was why Sir Kenelm was gifted with so many strange understandings.

‘I saw Eternity the other night

,’ he muttered to himself.

‘Like a great Ring of pure and endless light . . .’

The radio mast bleeped intermittently, alerting Kenelm to Immortality, Eternal Youth and Perfect Health – all within his scope, if he would only turn his mind to his loved ones’ advantage. He must think of his wife, but first, holding a candle and feeling happily paternal, Kenelm crept up the stairs with the hornspoon of night-bright silver medicine for his boy.

‘Animula vagula blandula

/

Hospes comeseque corporis.

’

The Emperor Hadrian’s purported deathbed address to his departing spirit – ‘My little wandering sportful soul/ Guest and companion of my body.’

‘Poor intricated soul! Riddling, perplexed, labyrinthical soul!’

John Donne’s sermon on the day of St Paul’s Conversion, 1629

IT WAS TWILIGHT,

and stray dogs and chained mastiffs were barking to one another across Whitehall; at Somerset House, cherubs with grotesque red cheeks were striking a French mechanical clock, calling Queen Henrietta-Maria’s friends and household to a Catholic evensong. The laying of the foundation stone of the Queen’s new chapel was to be celebrated, and it was the Digbys’ first public engagement since they arrived in town. It was a difficult invitation, dangerous to accept, foolish to decline.

Kenelm paced the rose garden of their manor at Charterhouse, wondering whether they should go. Young Kenelm was cured of his indisposition, and the surly blots on his cheeks should not hold them back from attending. If they went, they would find further favour with their Catholic Queen and her Catholic friends; they would know everyone there, and it would be a good beginning for Venetia’s return to public life. And yet Kenelm wanted to be more than the Queen’s cavaliero. He wanted to make comptroller of the King’s navy, but this would never come to pass while he played his Old Faith in public.

He and Venetia were usually discreet in their Catholicism; Chater ministered the mass to them in the chapel at Gayhurst in private, and they paid the fine for recusancy. That was that. To their neighbours they were ‘Catholics, yes, but not bad people’. Kenelm was careful to be an irreproachable landlord because every slip he made, every stag disputed or grain sack overpriced, was considered a Catholic vice; the local people always looked at him sideways, and every long word he used in conversation was taken as a foreign secret or a spell.