Understanding Sabermetrics (8 page)

Read Understanding Sabermetrics Online

Authors: Gabriel B. Costa,Michael R. Huber,John T. Saccoma

Hitting. It has consumed us, right up through these past years of the McGwire-Sosa-Bonds home run explosion. All of the players mentioned above, and scores of others were (or are) great hitters. But we will now ask a “What if?” question. This, in turn, will provide impetus for the idea of the EC.

Two of the national pastime’s most famous hitters were Ted Williams and Babe Ruth. Many have argued quite convincingly that one or the other was the greatest hitter ever. Williams’ career spanned four decades (1939- 1960) and Ruth’s twenty-two-year career went from 1914 until 1935. As great as their records were, however, their at-bats totals were relatively small: Ruth batted about 8400 times; Williams approximately 7700 times. Even when their base on balls totals are brought into the discussion (over 2000 for both sluggers), the number of times they each appeared at the plate pales in comparison to other great hitters. Williams was called into the armed forces twice: for World War II and during the Korean War. Ruth began his career as a pitcher, not playing every day; he also lost time due to suspensions (for example, in 1922 and 1925) and to illness (1925). In contrast, Pete Rose batted over 14,000 times and Hank Aaron had well over 12,000 at-bats.

Williams and Ruth were not the only ones with a lower-than-expected number of plate appearances; others, for one reason or another, had a similar fate. For example, Ruth’s teammate, Yankee legend Lou Gehrig, died before he reached the age of thirty-eight. Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax retired before his thirty-first birthday. And All-Star Don Mattingly will most probably be denied entrance into the Hall of Fame primarily because of his diminished career totals, brought on by a chronic back injury which led to his premature retirement. One wonders how the records of these three individuals — and many more — would read if their careers had been extended.

Returning to Williams and Ruth, we ask the following question: “Although they posted great numbers, can we speculate about or predict — in any reasonable way — what numbers they might have accumulated, given more hitting opportunities? Is there a plausible way to project or estimate what might have been, given different circumstances?

Specifically, we will attempt to answer three questions:

•

What would Williams’ totals have been had he not lost so much time?

•

What if Ruth had not started out as a pitcher?

•

Who was the greater hitter: Williams or Ruth?

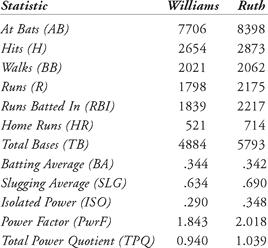

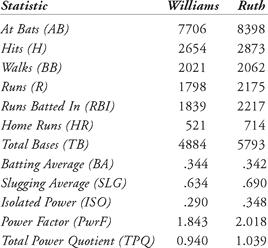

To give us a starting point regarding these questions, we consider the table below, which gives some of the career totals for both Hall of Famers (see Pre-Game : Abbreviations and Formulas at the beginning of this book for definitions):

Table 5.1 Williams versus Ruth — lifetime totals

To attempt to answer these questions, we will make three assumptions:

1. Let us suppose that both Williams and Ruth had, for the sake of argument, 12,500 plate appearances (PA). By a plate appearance we mean either an AB or a BB, neglecting both sacrifices and being hit by a pitch, since these numbers are relatively small compared to PA.

2. Furthermore, let us assume that their respective additional ABs are to be determined by preserving the ratio of AB to PA.

3. Finally, let’s introduce a special factor. Let us assume that Williams would have been 5% better for his time missed, since these years were prime years. As an added scenario, we will also assume that he would have been 10% better

.

At the same time, since Ruth pitched early in his career, we will suppose that for his added AB he would have been 5% less the hitter he was during the latter years of his career.

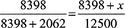

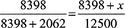

Let’s start with Ruth. From the table above, we see that the Babe had 8398 AB and 2062 BB for a total of 10,460 PA. Hence, if

x

is the number of additional AB, the following proportion preserves the AB to PA ratio:

x

is the number of additional AB, the following proportion preserves the AB to PA ratio:

To solve this equation for

x

, we merely “cross multiply” and isolate the unknown quantity to obtain

x

= 1638. So Ruth would get an additional 1638 AB. This implies that he would also receive an additional 402 BB, because 8398 AB + 1638 (additional AB) + 2062 BB + 402 (additional BB) = 12,500 PA.

x

, we merely “cross multiply” and isolate the unknown quantity to obtain

x

= 1638. So Ruth would get an additional 1638 AB. This implies that he would also receive an additional 402 BB, because 8398 AB + 1638 (additional AB) + 2062 BB + 402 (additional BB) = 12,500 PA.

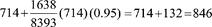

So, if Ruth was just as good as he always was for these extra 1638 AB, then his projected HR total would be:

We note that the term

is nothing more than a prorating of the 714 statistic. But we are assuming that Ruth would be 5 percent

is nothing more than a prorating of the 714 statistic. But we are assuming that Ruth would be 5 percent

less

the hitter he was during the rest of his career. Therefore, the

term should be multiplied by 0.95, giving the true projected HR figure as:

term should be multiplied by 0.95, giving the true projected HR figure as:

less

the hitter he was during the rest of his career. Therefore, the

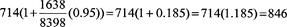

Note that the left-hand side of this last equation has a “714” in both terms. If we factor out the 714 (and recall that the number “1” is always an understood coefficient of any term), we see that

In other words, if we multiply 714 by the coefficient 1.185, we get the projected cumulative HR total for Babe Ruth.

We call this the

equivalence coefficient

, because it gives us a “reasonable” estimate of the desired cumulative HR total, given our defined “equivalent” scenario.

equivalence coefficient

, because it gives us a “reasonable” estimate of the desired cumulative HR total, given our defined “equivalent” scenario.

With regard to Ted Williams, his additional AB compute to 2197, while his additional BB come to 576. Using the 5 percent better and 10 percent better assumptions (giving kickers of 1.05 and 1.10, respectively), we find that the equivalence coefficients for Williams are 1.299 and 1.314, respectively. So, a 5 percent better Williams would hit 521(1.299) = 677 HR, while a 10 percent better Williams would project to 521(1.314) = 685 HR.

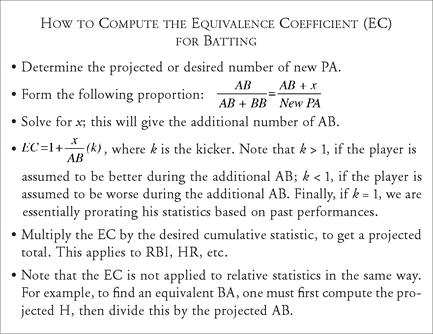

We summarize the technique of computing the EC in Figure 5.1.

Other books

Love Inspired Historical June 2014 Bundle: Lone Star Heiress\The Lawman's Oklahoma Sweetheart\The Gentleman's Bride Search\Family on the Range by Griggs, Winnie; Pleiter, Allie; Hale, Deborah; Nelson, Jessica

Dillon's Claim by Croix, Callie

Strike Eagle by Doug Beason

Swept off Her Feet by Browne, Hester

Tiger Born by Tressie Lockwood

Black Beech and Honeydew by Ngaio Marsh

The Windrose Chronicles 1 - The Silent Tower by Hambly, Barbara

The Kidnapped King by Ron Roy

Waiting for Perfect by Kretzschmar, Kelli

The Lady’s Secret by Joanna Chambers