Under the Sea to the North Pole (7 page)

Read Under the Sea to the North Pole Online

Authors: Pierre Mael

”Vive la France!” repeated every voice. And Schnecker, who felt he was watched, did as the others did, and shouted, “Vive la France!”

”We must finish the evening pleasantly,” said Isabelle.

Everything had been provided for. The piano was there, landed the day before from the

Polar Star.

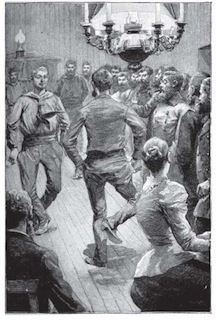

Isabelle sat down to it, and her active fingers ran up and down the keyboard. The officers set the example, and strove to excel each other in making merry up to an advanced hour of the night. The most eccentric dances were indulged in. Besides waltzes, polkas, and quadrilles many out-ofthe-way saltatory performances were introduced. The Canadians danced jigs more or less Scottish in character; the Bretons indulged in other eccentricities of a more or less uncivilized character.

Isabelle took part in the general merry-making, availing herself of the arm of Hubert D’Ermont, her betrothed. Lieutenant Pol and Doctor Servan were both musicians and quite expert on the piano, and took turns in relieving Mademoiselle De Keralio.

There were songs, comic and sentimental, according to the repertory of the singers. Some gave recitations either in verse or prose. To wind up with, Schnecker gave a magic lantern entertainment, for which he was heartily cheered.

At two o’clock in the morning as the day closed in all went to bed, peaceful in heart and joyful in mind.

Half an hour afterwards all in the encampment were asleep, and the cold, insidious and morose, brought the mercury down in the tube, the temperature outside falling to twenty below zero.

One only was not asleep; and he was Schnecker, the chemist.

He had obtained permission from the first to sleep in the laboratory, of which he had the entire charge. Although the atmosphere was growing colder and colder, he remained standing by the side of his bed, frowning, and with his hands clenched.

And from time to time a grunt escaped from his lips.

“Oh! This D’Ermont, curse him! How I hate him! Am I always to be his laughing-stock? In what a tone of haughty contempt he replied to my objections.”

He stopped and took three turns in his room.

“But if he is right? If he told the truth? Is it really possible? And what is the permanent body his brother has been able to solidify? Yes, what? As far as I know only nitrogen is likely to be treated in that way. But what could he do with nitrogen? Nothing. We do not want to fertilize the lands of the pole, nor to provide these poorly combustible regions with oxygen. Besides, he spoke of a gas which was both combustible and a source of power. Can it be hydrogen?”

He started, and remained for a few seconds in deep thought. Resuming his walk, he gave his anger full course. Exclamations and fragmentary phrases came from his lips in jerks.

“Madmen! Idiots who believe it! The fable of Cailletet liquefying hydrogen! A story of a French invention! 240 atmospheres of pressure! And Pictet even solidifying it at 650 atmospheres! Think of it!”

He crossed his arms, and looking at the furnaces, crucibles and retorts in front of him, said,—

“ If the thing had been possible, would not my German fellow-countrymen have discovered it? Is it only these Celts that are capable of such things?”

But he could not convince himself; he could not believe it.

“Really, I know not why I mention these names of Germany and France? Do they mean anything in my eyes? Are they not on the contrary mere narrow credulities, degrading predilections, words realizing that most absurd of conceptions, patriotism! I have no country: I renounce them all. Mine disgraced me and condemned me to death for an action which those brachycephalous boobies full of beer called a crime against common humanity.”

He stopped. The sound of a voice reached him from the room next door.

Unmindful of the cold, he took off his boots, blew out the light, and placed his ear at the keyhole. He was not mistaken. There was talking going on in the next room.

The room next to the laboratory was Isabelle’s. It was the best sheltered. At this moment Isabelle, with her father and Doctor Servan, were listening to Hubert as he developed his theories.

And the traitor Schnecker, panting, with his heart full of bitterness, listened as in echo to his own words, to the lieutenant explaining to his select audience the secret on which the success of the expedition was to depend.

“Yes,” said Hubert, “the things I showed you were cylinders of aluminium, enclosing steel tubes bored in the original ingot. These tubes all end in a tap closed by a screw permitting the sudden or gradual escape, as you please, of the liquefied hydrogen gas it contains.”

“Hydrogen!” the three listeners could not help exclaiming, as they started in their chairs. “Hydrogen!” repeated Schnecker to himself, as he clenched his fists.

“Yes” proudly said Hubert, “that is the discovery which will render immortal the name of my brother, Marc D’Ermont.”

The German had recovered himself. He felt not the cold all he felt was his anger. In the darkness which enveloped him his conscience was luminous enough with its hate and jealousy.

“Your brother’s glory!” he murmured. “If you have told the truth, Hubert D’Ermont, if this admirable discovery has been really made, it will be known nowhere beyond the glacial desolate land where we are, and it will die unknown to the rest of mankind.”

At this moment a short guttural bark was uttered from the other side of the door.

“Ah!” said Schnecker, in a low voice, “the dog is also there!”

There was silence in Isabelle’s room; and then the German distinctly heard them say,—

“There is some one in the laboratory! Let us look!”

The chemist saw the danger of being caught in the darkness. Quickly he struck a match and lighted the candle, so that when Hubert appeared at the door, followed by his companions and Salvator, all looking exceedingly suspicious, they found Schnecker peacefully inspecting the interior of a retort.

“Confound it! Monsieur Schnecker,” said the doctor, “you are going in for frost-bites of the first water!”

This remark recalled the chemist to a sense of his position.

He shivered; and looking at his hands, he saw they were quite blue.

“How careless you are!” said Servan. “Quick, get into Mademoiselle de Keralio’s room, or in two minutes you will lose your legs.”

And he pushed him into the warm room, which the mere opening of the door had sent down ten degrees in temperature.

When Schnecker had gone, the others looked at each other with painful surprise. The unexpected meeting had certainly not removed their suspicions. Quite the contrary. The chemist, warmed and refreshed, could remember only one thing. He had seen in Isabelle’s room the strong box he had seen in Hubert’s cabin on the ship. They had forgotten to shut it, and through the half-open door he could distinguish a quantity of tubes stored away in its depths.

CHAPTER V

WINTER QUARTERS.

T

HE cold had returned triumphantly to its empire in the polar night, which draped the sky in its veils of grief. Owing to the wise prevision which had been present at the construction and installation of Fort Esperance, the winterers had not as yet suffered much. Between’‘ the terrible temperature without and that of the stoves constantly burning within, there was a difference of from thirty to forty degrees.

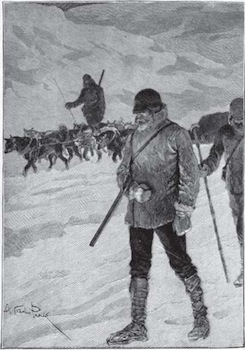

By the advice of the two doctors there had been erected before each door a kind of halfway shed, to enable the men going out to become accustomed to the enormous difference between the two temperatures. What remained of the day was not worthy of the name. It was a kind of vague twilight, occasionally edged with the brilliant hues of the extreme horizon. In preparation for the grand departure fixed for the 15th of April, the shortening days of autumn had been devoted to explorations in the neighbourhood, and bit by bit the travellers became acquainted with their domain. These expeditions were always accompanied by sledges drawn sometimes by dogs, sometimes by the men themselves. In either case the apprenticeship was a bitter one, and every day the pole more clearly showed with what bitterness of resistance it would defend its frontier against human curiosity.

The first sledge journeys were terrible. The men were not yet acclimatized to these frightful temperatures of 24, 28, 32 and 36 degrees below zero, which lasted from the 15th of October to the 1st of May. And yet the travellers had availed themselves of the experiences of their predecessors. In place of thick heavy materials, they had adopted for their clothes soft light woollen stuffs, which gave their limbs full play. A double pair of trousers, a knitted vest with a jacket of cotton flannel, a short overcoat of fur, a cap with the fur inside out, cloth boots with heavily nailed soles, woollen mittens over fur gloves, such was the men’s costume.

Isabelle, it need scarcely be said, had adopted a somewhat similar costume, prepared some time before. As to the nurse, Tina Le Floc’h, she looked in her winter garb not unlike a wild beast, and her width of shoulders and heavy gait made the illusion all the greater at a distance.

De Keralio set the example of courage and resistance. On the 15th of October, accompanied by his friend Dr. Servan and the sailors Guerbraz and Carré, he undertook, with an outfit of a dozen dogs, the exploration of the coast. Starting from the camp, that is from Cape Ritter, on the 76th parallel, the explorers passed Cape Bismarck, and boldly kept on towards the north. The coast continued almost straight up to the 79th degree; there it trended to the west, and the travellers noted with pleasure that this obliquity continued at a sufficient angle to enable them to reach by the land route Cape Washington, seen by Lockwood in 1882. It remained to be seen if the route by the sea would be equally practicable.

This first excursion, accomplished through snowstorms and in a mean temperature of 18 degrees below zero, ended at the 81st degree. A peak indistinctly seen in the north-west received the name of Mount Keralio at the same time as that of Cape Servan was given to the promontory beyond which the explorers did not go.

They had to return. They had accomplished 125 kilometres

during the first four days. Then their strength began to fail, the route became more difficult, the cold more keen, and they could not cover more than 25 kilometres a day. The exploration lasted a little more than four weeks. The sleeping-bags of buffalo skin were the great resource of the poor pioneers. They returned weakened by fatigue, exhausted by cold. Luckily the welcome they received at the station soon put them on their feet. It was a curious thing that Guerbraz, the most robust of the party, suffered the most; his left ear was partially frozen.

In turn the different detachments went out, some towards the north, others towards the west. They were fortunate enough to secure a few kilos of fresh meat which advantageously varied the bill of fare. In fact pemmican and compressed bread had quickly fatigued both palates and stomachs.

The winter and the long night condemned the travellers - to repose. They could not attempt to take with them the light indispensable for their road, and the hummocks and gullies were too full of danger for them to venture among them in the dark. The order of the day was therefore given in accordance with the reports of former winterers, and they remained by the fireside.