Under the Sea to the North Pole (10 page)

Read Under the Sea to the North Pole Online

Authors: Pierre Mael

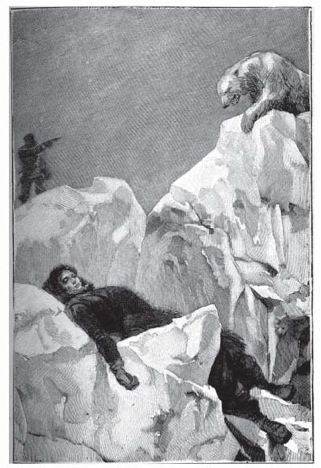

Running to the edge of the shelf, she tried to get down. Alas! the edge broke away vertically under her. The wall of ice had no breaks in it.. It was as smooth as marble.

She waved her arms. The wind bore her voice towards him, and Guerbraz heard but the one word,—

“Cannot.”

On the other side of the block the bear, now hidden from the sailor’s view, began to scale the berg. Its laborious ascent can be imagined.

Never had poor Guerbraz suffered so cruelly. A desperate resolve came to him. He rushed to the foot of the floeberg, and opening his arms, prepared to catch Isabelle as she slipped down.

It was a mad resolve, but justified in a great measure by the confidence he placed in his almost superhuman strength.

Isabelle shared in that confidence, for, approaching the edge, she measured with a glance the height of the fall. The sight frightened her evidently, for she stepped back to the ledge.

But at the same instant there appeared the head of the bear, with its bloodshot eyes and red throat. The girl, overcome by her feelings, tottered and fell in a faint. Guerbraz took the best aim at the brute that he could, and the bullet entered the bear’s left eye. The monster, made more furious by the wound, gave a hoarse growl, and hurried towards his inanimate prey. Isabelle was lost. But then for the second time occurred the phenomenon which had just detached the floeberg from the coast. The peak shook, cracked, and, splitting all along its length, divided into two huge masses. The bear was thrown back, while Isabelle slipped gently down and disappeared over the crevasse which had just opened. This was not the same kind of death for her, but death it was, none the less. Without another thought for the bear, which had fled, seized with terror at this second misadventure, Guerbraz leaped towards the crack, at the risk of being swallowed up himself. He could see Isabelle had fainted, suspended between heaven and earth, hooked up by the thick cloak she was wearing. If the ice moved again, she would be hurled into the horrible fissure, and one of the blocks around would be her tombstone. All seemed lost, and without some providential intervention Isabelle De Keralio was doomed. But just then, on the rugged bergs, some of the hunters appeared. Attracted by the two shots fired by Guerbraz, they had come up to see the bear’s flight and Isabelle’s fall. Ten men leapt on the floe and set about saving her. Alas! All their efforts would have been in vain had it not been for Salvator. The good dog did not hesitate. In a few prodigious leaps he had reached the crevasse, and with wonderful dexterity had gripped the cloak in his teeth and carefully drawn it over the outer slope of the chasm, where Guerbraz and his companions could catch Isabelle in their arms. In a minute or two a sort of stretcher was formed with guns and hunting spears, on which to carry the inanimate girl. At the fort the consternation was great, but Dr. Servan and his colleague promptly reassured the colony.

Isabelle was condemned to a week’s rest. Had she not to recover all her strength before her departure for the North?

The return of the sun not only marked the end of the cold, but the end of the imprisonment. From the depth of every heart rose a hymn of gratitude and blessing towards the Creator.

The moment had come to enter resolutely on the campaign, and advance without a pause towards its last stage. Once the 85th parallel was reached, they could hope for final triumph, if the land continued beyond the horizons that were seen by their heroic predecessors.

Many there were, all perhaps, who regretted leaving Fort Esperance. They had been so happy there. What would they find in this unknown towards which they were about to start? Could all the wonders realized here be reproduced further to the north, if the camp were established on the same bases and with the same foresight as it had been at Cape Ritter? But the very hypothesis of a journey direct to the Pole rendered this eventuality quite problematic. It was to be a life under tents added to a life on board ship, if the rigours of the Pole allowed.

But the time taken in preparations was spent by the explorers in further preliminary excursions. D’Ermont and Pol were the first to try the Polar route. Their observations confirmed those already made by De Keralio and Doctor Servan. The coast of Greenland trended off at Cape Bismarck, and unless there was a long peninsula, of which there was no evidence, it no longer deserved its name of east coast, inasmuch as it ran towards the north-east.

After the 20th of March the ship was prepared for the reception of the explorers, who began to take up their Quarters on board. In order that they might not be inconvenienced by the change, Hubert, with Schnecker’s assistance, set up the hydrogen apparatus, and such was the effect of the radiation of the heat on the ice, that the cradle, gradually relieved of the lateral pressure, let the ship down. Jets of steam were then turned on, with a view of assisting in breaking the ice up, and on the 1st of April the steamer’s keel sank through the thin coating and resumed contact with the water.

Then the wooden house was taken down and its materials brought on board. This was not the lightest task nor the easiest. The cold was still very great, and in the course of the work several of the men who had hitherto escaped were seriously afflicted, owing to their neglect of the precautions that were daily advised. One or two amputations of frost-bitten fingers had to be undertaken, and the infirmary of the

Polar Star

received six patients, more or less gravely injured, before the time came for the vessel to leave the sheltering fiord for the open sea. Nevertheless the enthusiasm of the crew continued unabated. The sun had called to new life the gaiety which had not seriously suffered during the long darkness of the winter months. But what contributed more than all to revive the enthusiasm was the appearance of the crop about the loth of April.

The greenhouse had been left untouched. Who knew if they would not again have to seek the shelter of Cape Ritter? It had consequently been converted into a store and in it had been deposited all the reserves of fresh meat that had not been used up, and which were due to the guns of the most skilful hunters of the colony.

The greenhouse had yielded astonishing results. Under the four electric suns of the lamps, and owing to the constant heat, the nitrogenized sand of the borders had produced as much as the rich mould of the temperate zones. There had been yielded from eighty to a hundred carrots, thirty boxes of radishes, which the sailors declared were of excellent flavour, a dozen boxes of landcress, and more than a hundred and forty heads of lettuces.

The fruit was not so abundant. There were not quite two salad bowls of strawberries, but their want of colour was the cause of some disappointment, although with the addition of sugar they were declared to be miraculous. Isabelle was able to gather a nosegay for herself besides enough flowers to give as buttonholes for all the crew, and it was with this new-fashioned decoration that the whole party, in health and out of it, took part in the farewell banquet given on board the steamer. Long and uproarious cheers greeted the heroine who was at one and the same time the beneficent fairy and the sister of charity of the expedition. And after that the party broke up, not without profound emotion.

Captain Lacrosse was again in charge of the crew he deemed necessary for the working of the ship. He also took on board the sick and wounded, and their presence decided Isabelle to remain with them in company with her faithful nurse. Doctor Servan with some regret gave up his place in the land column to Le Sieur.

It was agreed, however, that this column should keep to the coast, parallel to the course of the ship, so as to remain in communication with her as much as possible.

On the 20th of April, after a strong breeze from the south the sky seemed clear of cloud, and the sun, already high on the horizon, raised the temperature to two degrees. This difference in the height of the thermometer was announced by long crackings from the open sea; and on the 21st De Keralio and Lacrosse, ascending one of the neighbouring hills, saw a wide channel of open water extending to within 600 yards of the shore.

On the 26th the floe on which lay the

Polar Star

split along its entire length, and all that remained of the scaffolding had to be hurriedly taken on board. Gradually the floe broke away, block after block, and drifted out to sea. So rapid was this drifting that the men of the land expedition had no time to disembark, and had to stay on board until the steamer could get quite clear and put them ashore at Cape Bismarck. This was effected on the 30th, the

Polar Star

not being able to extricate herself until she had drifted half a degree towards the south.

On the 1st of May the final landing took place, the exploring column consisting of De Keralio, D’Ermont, Hardy, Doctor Le Sieur, and the sailors Carré, Leclerc, Julliat, Binel and MacWright. In charge of the men, as first boatswain, was Guerbraz.

To compel the party to keep in constant communication with the ship, only three days’ provisions were taken This was the best way of controlling the victualling, and it also meant the minimizing of the baggage. The march under such circumstances would be all the easier. Unless a catastrophe came which it was impossible to foresee they should reach Cape Washington in a month, for it was only 350 kilometres away.

The fine season was of immense assistance to the explorers. There had been some fear lest the

Polar Star

could not go northwards. But on this point the witnesses were contradictory. Nares and Markham, who were’ stopped on the l2th May at 83° 20' 26"

,

had nothing before them but the unbroken pack of the palaeocrystic sea. Lockwood and Brainard, who reached 83° 23' 6", had to retreat on account of the dislocation of the ice and the presence of numerous channels in the pack. Which was right, the English or the American view? . They were soon to find out for themselves.

CHAPTER VII

CAPE WASHINGTON

T

HE first stage appeared to show that the English were column had not gone ten miles to the northward before it had to stop. The steamer was lost sight of.

It was manifest that the

Polar Star

was engaged in a bitter struggle with the ice, and would have to force her way foot by foot. As far as the travellers’ view could reach, the sea was covered with ice. It was a gloomy plain, varied in places with low humps and chains of hummocks. There was nothing moving on it, add this. silent immobility gave it a most desolate appearance.

The column halted and pitched its tent. They were to bivouac until the arrival of the ship. If it did not come that would be proof certain that they would have to renounce the hope of the voyage by sea.

All through the night they waited with eager hearts. No one had cared to anticipate this discouraging eventuality. And no one resigned himself to it; and when they thrust themselves into their sleeping bags, notwithstanding the mildness of the temperature, regret at having left their comfortable house was added to the irritation caused by hope deceived “My friends,” said De Keralio, “to put an end to this painful anxiety, the best thing we can do is to adjourn our conjectures until to-morrow, and to go to sleep.”

They did not sleep very long. Towards midnight the wind rose, a wind from the south which gave the key-note to the clamours of the pack. The short hours of the morning were full of these lugubrious rumours, and the travellers, unaccustomed during the winter to sleep in the open air, were a long time getting used to them; and it was with unmixed joy that they saw the day reappear.

Terrible crackings were still echoing to the roaring of the wind, and several times the ears of those who could not sleep had recognized the hard, sharp beat of the waves on the coast ice; and hope returned to them, for the noise was of good augury and foretold the breaking up of the ice field.

And yet those who heard it first dare not confide their hopes to others. Knowing how cruel a disillusion would be to themselves, they preferred to spare their sleeping companions.

But when dawn came there could be no doubt of it. It was the sea, tlie green salt sea they had under their eyes. Of the immense ice field of the night before there was nothing but a few gigantic fragments here and there, drifting to the east in a current visible to the naked eye.