Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (8 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

Weeks later, Japan withdrew as host of the 1940 Olympics, and the Games were transferred to Finland. Adjusting his aspirations from Tokyo to Helsinki, Louie rol ed on. He won every race he contested in the 1939 school season. In the early months of 1940, in a series of eastern indoor miles against the best runners in America, he was magnificent, taking two seconds and two close fourths, twice beating Cunningham, and getting progressively faster. In February at the Boston Garden, he ran a 4:08.2, six-tenths of a second short of the fastest indoor mile ever run.* At Madison Square Garden two weeks later, he scorched a 4:07.9, caught just before the tape by the great Chuck Fenske, whose time equaled the indoor world record. With the Olympics months away, Louie was peaking at the ideal moment.

With a cracked rib and puncture wounds to both legs and one foot, Louie celebrates his record-setting NCAA Championship victory. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

——

As Louie blazed through col ege, far away, history was turning. In Europe, Hitler was laying plans to conquer the continent. In Asia, Japan’s leaders had designs of equal magnitude. Poor in natural resources, its trade crippled by high tariffs and low demand, Japan was struggling to support a growing population. Eyeing their nation’s resource-rich neighbors, Japan’s leaders saw the prospect of economic independence, and something more. Central to the Japanese identity was the belief that it was Japan’s divinely mandated right to rule its fel ow Asians, whom it saw as inherently inferior. “There are superior and inferior races in the world,” said the Japanese politician Nakajima Chikuhei in 1940, “and it is the sacred duty of the leading race to lead and enlighten the inferior ones.” The Japanese, he continued, are “the sole superior race of the world.” Moved by necessity and destiny, Japan’s leaders planned to “plant the blood of the Yamato [Japanese] race” on their neighboring nations’ soil. They were going to subjugate al of the Far East.

Japan’s military-dominated government had long been preparing for its quest. Over decades, it had crafted a muscular, technological y sophisticated army and navy, and through a military-run school system that relentlessly and violently dril ed children on the nation’s imperial destiny, it had shaped its people for war. Final y, through intense indoctrination, beatings, and desensitization, its army cultivated and celebrated extreme brutality in its soldiers.

“Imbuing violence with holy meaning,” wrote the historian Iris Chang, “the Japanese imperial army made violence a cultural imperative every bit as powerful as that which propel ed Europeans during the Crusades and the Spanish Inquisition.” Chang cited a 1933 speech by a Japanese general:

“Every single bul et must be charged with the Imperial Way, and the end of every bayonet must have National Virtue burnt into it.” In 1931, Japan tested the waters, invading the Chinese province of Manchuria and setting up a fiercely oppressive puppet state. This was only the beginning.

In the late 1930s, both Germany and Japan were ready to move. It was Japan that struck first, in 1937, sending its armies smashing into the rest of China. Two years later, Hitler invaded Poland. America, long isolationist, found itself pul ed into both conflicts: In Europe, its al ies lay in Hitler’s path; in the Pacific, its longtime al y China was being ravaged by the Japanese, and its territories of Hawaii, Wake, Guam, and Midway, as wel as its commonwealth of the Philippines, were threatened. The world was fal ing into catastrophe.

On a dark day in April 1940, Louie returned to his bungalow to find the USC campus buzzing. Hitler had unleashed his blitzkrieg across Europe, his Soviet al ies had fol owed, and the continent had exploded into total war. Finland, which was set to host the summer Games, was reeling. Helsinki’s Olympic stadium was partial y col apsed, toppled by Soviet bombs. Gunnar Höckert, who had beaten Louie and won gold for Finland in the 5,000 in Berlin, was dead, kil ed defending his homeland.* The Olympics had been canceled.

——

Louie was unmoored. He became il , first with food poisoning, then with pleurisy. His speed abandoned him, and he lost race after race. When USC’s spring semester ended, he col ected his class ring and left campus. He was a few credits short of a degree, but he had al of 1941 to make them up. He took a job as a welder at the Lockheed Air Corporation and mourned his lost Olympics.

As Louie worked through the summer of ’40, America slid toward war. In Europe, Hitler had driven the British and their al ies into the sea at Dunkirk. In the Pacific, Japan was tearing through China and moving into Indochina. In an effort to stop Japan, President Franklin Roosevelt imposed ever-increasing embargoes on matériel, such as scrap metal and aviation fuel. In the coming months, he would declare an oil embargo, freeze Japanese assets in America, and final y declare a total trade embargo. Japan pushed on.

Lockheed was on a war footing, punching out aircraft for the Army Air Corps and the Royal Air Force. From the hangar where he worked, Louie could see P-38 fighters cruising overhead. Ever since his trip in the air as a boy, he’d been uneasy about planes, but watching the P-38s, he felt a pul . He was stil feeling it in September when Congress enacted a draft bil . Those who enlisted prior to being drafted could choose their service branch. In early 1941, Louie joined the Army Air Corps.*

Sent to the Hancock Col ege of Aeronautics in Santa Maria, California, Louie learned that flying a plane was nothing like watching it from the ground.

He was jittery and dogged by airsickness. He washed out of the air corps, signed papers that he didn’t bother to read, and got a job as a movie extra. He was working on the set of They Died with Their Boots On, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havil and, when a letter arrived. He’d been drafted.

Louie in training. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

The induction date fel before the Flynn film would wrap, and Louie stood to earn a bonus if he stayed through the shoot. Just before his army physical, he ate a fistful of candy bars; thanks to the consequent soaring blood sugar, he failed the physical. Ordered to return a few days later to retake the test, he went back to the set and earned his bonus. Then, on September 29, he joined the army.

When he finished basic training, he had an unhappy surprise. Because he hadn’t read his air corps washout papers, he had no idea that he’d agreed to rejoin the corps for future service. In November 1941, he arrived at El ington Field, in Houston, Texas. The military was going to make him a bombardier.

——

That fal , while Louie was on his way to becoming an airman, an urgent letter landed on the desk of J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI. It had come from a brigadier general at the War Department, Military Intel igence Division. The letter said that a credible informant had warned military officials that a California man, believed to be working for an innocuous local Japanese organization, had in fact been an employee of the Japanese navy, on assignment to raise money for Japan’s war effort. Japanese naval superiors had recently transferred the man to Washington, D.C., the informant said, to continue acting under their orders. According to the informant, the man was known as “Mr. Sasaki.” It was Louie’s friend Jimmie.

Though the surviving records of the informant’s report contain no details of Sasaki’s al eged activities, according to notes made later by a captain of the Torrance police, Sasaki had been making visits to a field adjacent to a power station, just off of Torrance Boulevard. There, he had erected a powerful radio transmitter, which he had used to send information to the Japanese government. If the al egation was true, it would explain Sasaki’s mysterious trips to Torrance. Louie’s good friend may have been a spy.

Sasaki had indeed moved to Washington, D.C., in the employ of the Japanese navy. He worked in the Japanese embassy and lived in an apartment building popular among congressmen. He made himself wel known among the Washington elite, mixing with legislators at building cocktail parties, playing golf at the Army Navy Country Club, socializing with police officers and State Department officials, and volunteering to serve as chauffeur after parties. Just whose side he was on is unclear; at a cocktail party, he gave a congressman sensitive information on Japanese aircraft manufacturing.

The letter to the FBI set off alarm bel s. Hoover, concerned enough to plan on informing the secretary of state, ordered an immediate investigation of Sasaki.

——

Not long after sunrise on a Sunday in December, a pilot guided a smal plane over the Pacific. Below him, the dark sea gave way to a strand of white: waves slapping the northern tip of Oahu Island. The plane flew into a bril iant Hawaiian morning.

Oahu was beginning to stir. At Hickam Field, soldiers were washing a car. On Hula Lane, a family was dressing for Mass. At the officers’ club at Wheeler Field, men were leaving a poker game. In a barracks, two men were in the midst of a pil ow fight. At Ewa Mooring Mast Field, a technical sergeant was peering through the lens of a camera at his three-year-old son. Hardly anyone had made it to the mess hal s yet. Quite a few were stil sleeping in their bunks in the warships, gently swaying in the harbor. Aboard the USS Arizona, an officer was about to suit up to play in the United States Fleet championship basebal game. On deck, men were assembling to raise flags as a band played the national anthem, a Sunday morning tradition.

Far above them, the pilot counted eight battleships, the Pacific Fleet’s ful complement. There was a faint sheet of fog settled low to the ground.

The pilot’s name was Mitsuo Fuchida. He rol ed back the canopy on his plane and sent a flare skidding green across the sky, then ordered his radioman to tap out a battle cry. Behind Fuchida, 180 Japanese planes peeled away and dove for Oahu.* On the deck of the Arizona, the men looked up.

In the barracks, one of the men in the pil ow fight suddenly fel to the floor. He was dead, a three-inch hole blown through his neck. His friend ran to a window and saw a building heave upward and crumble down. A dive-bomber had crashed straight into it. There were red circles on its wings.

——

Pete Zamperini was at a friend’s house that morning, playing a few hands of high-low-jack before heading out for a round of golf. Behind him, the sizzle of waffles on a griddle competed with the chirp of a radio. An urgent voice interrupted the broadcast. The players put down their cards.

In Texas, Louie was in a theater, on a weekend pass. The theater was thick with servicemen, taking breaks from the endless dril ing that was the life of the peacetime soldier. Midway through the showing, the screen went blank, light flooded the theater, and a man hurried onto the stage. Is there a fire?

Louie wondered.

Al servicemen must return to their bases immediately, the man said. Japan has attacked Pearl Harbor.

Louie would long remember sitting there with his eyes wide, his mind floundering. America was at war. He grabbed his hat and ran from the building.

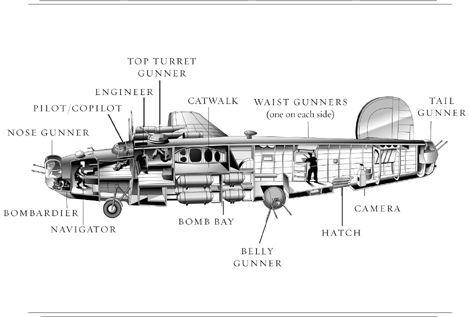

B-24 LIBERATOR

* Because indoor tracks are shorter than outdoor ones, forcing runners to make more turns to cover the same distance, indoor records are general y slower. In 1940, the outdoor mile world record was one second faster than the indoor record.

* Höckert’s teammate Lauri Lehtinen, the 1932 5,000-meter Olympic champion, gave his gold medal to another Finnish soldier in Höckert’s honor.

* Many other great runners also enlisted. When Norman Bright tried to sign up, he was rejected because of his alarmingly slow pulse, a consequence of his extreme fitness. He solved the problem by running three miles, straight into another enlistment office. Cunningham tried to join the navy, but recruiters, seeing his grotesquely scarred legs, assumed that he was too crippled to serve. When someone came in and mentioned his name, they realized who he was and signed him in.

* One hundred and eighty-three planes were launched in this first of two waves, but two were lost on takeoff.