Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (11 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

——

On a Saturday afternoon in mid-October of 1942, the men of the 372nd were told to pack their bags. Their training was being cut short, and they were to be sent to California’s Hamilton Field, then rushed overseas. Phil was crestfal en; Cecy was about to come see him. He would miss her by three days. On October 20, the squadron flew out of Iowa.

At Hamilton Field, an artist was working his way down the planes, painting each one’s name and accompanying il ustration. Naming bombers was a grand tradition. Many B-24 crews dreamed up delightful y clever names, among them E Pluribus Aluminum, Axis Grinder, The Bad Penny , and Bombs Nip On. Quite a few of the rest were shamelessly bawdy, painted with scantily clad and unclad women. One featured a sailor chasing a naked girl around the fuselage. Its name was Willie Maker. Louie had a snapshot taken of himself grinning under one of the more ribald examples.

Phil’s plane needed a name, and no one could think of one. After the war, the survivors would have different memories of who named the plane, but in a letter penned that fal , Phil would write that it was copilot George Moznette who suggested Super Man. Everyone liked it, and the name was painted on the plane’s nose, along with the superhero himself, a bomb in one hand and a machine gun in the other. Louie didn’t think much of the painting—in photographs, the gun looks like a shovel—but Phil loved it. Most crews referred to their planes as “she.” Phil insisted that his plane was al man.

The men were slated for combat, but they hadn’t been told where they would serve. Judging by the heavy winter gear, Louie thought that they were bound for Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, which had been invaded by the Japanese months before. He was happily wrong: they were going to Hawaii. On the evening of October 24, Louie cal ed home for a last good-bye. He just missed Pete, who came for a visit only a few minutes after his brother hung up.

Sometime after speaking to Louie, Louise pul ed out a set of note cards on which she kept lists of Christmas card recipients. After Louie’s last visit home, she’d taken out one of the cards and, on it, jotted down the date and a few words about Louie’s departure. This day, she noted Louie’s phone cal .

These were the first two entries in what would become Louise’s war diary.

Phil at the helm of Super Man. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

Before he left Hamilton Field, Louie dropped a little package in the mail, addressed to his mother. When Louise opened it, she found inside a pair of airman’s wings. Every morning, through al that lay ahead for her, Louise would pin the wings to her dress. Every night, before she went to bed, she’d take them off her dress and pin them to her nightgown.

——

On November 2, 1942, Phil’s crew climbed aboard Super Man and readied to go to war. They were heading into a desperate fight. North to south, Japan’s new empire stretched five thousand miles, from the snowbound Aleutians to Java, hundreds of miles south of the equator. West to east, the empire sprawled over more than six thousand miles, from the border of India to the Gilbert and Marshal islands in the central Pacific. In the Pacific, virtual y everything above Australia and west of the international date line had been taken by Japan. Only a few eastward islands had been spared, among them the Hawaiian Islands, Midway, Canton, Funafuti, and a tiny paradise cal ed Palmyra. It was from these outposts that the men of the AAF were trying to win the Pacific, as the saying went, “one damned island after another.”

That day, Super Man banked over the Pacific for the first time. The crew was bound for Oahu’s Hickam Field, where the war had begun for America eleven months before, and where it would soon begin for them. The rim of California slid away, and then there was nothing but ocean. From this day forward, until victory or defeat, transfer, discharge, capture, or death took them from it, the vast Pacific would be beneath and around them. Its bottom was already littered with downed warplanes and the ghosts of lost airmen. Every day of this long and ferocious war, more would join them.

* In June 1941, the air corps became a subordinate arm of the Army Air Forces. It remained in existence as a combat branch of the army until 1947.

S even

“This Is It, Boys”

OAHU WAS STILL RINGING FROM THE JAPANESE ATTACK. The enemy had left so many holes in the roads that the authorities hadn’t been able to fil them al yet, leaving the local drivers swerving around craters. There were stil a few gouges in the roof of the Hickam Field barracks, making for soggy airmen when it rained. The island was on constant alert for air raids or invasion, and was so heavily camouflaged, a ground crewman wrote in his diary, that “one sees only about ⅓ of what is actual y there.” Each night, the island disappeared; every window was fitted with lightproof curtains, every car with covered headlights, and blackout patrols enforced rules so strict that a man wasn’t even permitted to strike a match. Servicemen were under orders to carry gas masks in hip holsters at al times. To reach their beloved waves, local surfers had to worm their way under the barbed wire that ran the length of Waikiki Beach.

The 372nd squadron was sent to Kahuku, a beachside base at the foot of a blade of mountains on the north shore. Louie and Phil, who would soon be promoted to first lieutenant, were assigned to a barracks with Mitchel , Moznette, twelve other young officers, and hordes of mosquitoes. “You kil one,”

Phil wrote, “and ten more come to the funeral.” Outside, the building was picturesque; inside, Phil wrote, it looked “like a dozen dirty Missouri pigs have been wal owing on it.” The nonstop revelry didn’t help matters. After one four A.M. knock-down, drag-out water fight involving al sixteen officers, Phil woke up with floor burns on his elbows and knees. On another night, as Louie and Phil wrestled over a beer, they crashed into the flimsy partition separating their room from the next. The partition keeled over, and Phil and Louie kept staggering forward, toppling two more partitions before they stopped. When Colonel Wil iam Matheny, the 307th Bomb Group commander, saw the wreckage, he grumbled something about how Zamperini must have been involved.

There was one perk to life in the barracks. The bathroom was plastered in girlie pinups, a Sistine Chapel of pornography. Phil gaped at it, marveling at the distil ation of frustrated flyboy libido that had inspired it. Here in the pornographic palace, he was a long way from his minister father’s house in Indiana.

——

Everyone was eager to take a crack at the enemy, but there was no combat to be had. In its place were endless lectures, endless training, and, when Moznette was transferred to another crew, the breaking in of a series of temporary copilots. Eventual y, Long Beach, California, native Charleton Hugh Cuppernel joined the crew as Moznette’s replacement. A smart, jovial ex–footbal player and prelaw student, built like a side of beef, Cuppernel got along with everyone, dispensing wisecracks through teeth clenched around a gnawed-up cigar.

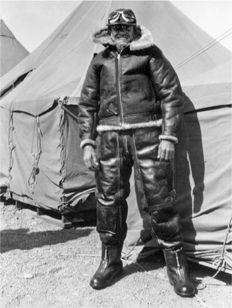

Louie, ready for the chil of high altitude. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

When they first went up over Hawaii, the men were surprised to learn that their arctic gear hadn’t been issued in error. At ten thousand feet, even in the tropics, it could be sharply cold, and occasional y the bombardier’s greenhouse windows froze. Only the flight deck up front was heated, so the men in the rear tramped around in fleece jackets, fur-lined boots, and, sometimes, electrical y heated suits. The ground crewmen used the bombers as flying iceboxes, hiding soda bottles in them and retrieving them, ice-cold, after missions.

Training mostly over Kauai, the men discovered their talent. Though they had a few mishaps—Phil once taxied Super Man straight into a telephone pole—in aerial gunning, they nailed targets at a rate more than three times the squadron average. Louie’s bombing scores were outstanding. In one dive-bombing exercise, he hit the target dead center seven of nine times. The biggest chore of training was coping with the nitpicking, rank-pul ing, much-loathed lieutenant who oversaw their flights. Once, when one of Super Man’s engines quit during a routine flight, Phil turned the plane back and landed at Kahuku, only to be accosted by the furious lieutenant in a speeding jeep, ordering them back up. When Louie offered to fly on three engines so long as the lieutenant joined them, the lieutenant abruptly changed his mind.

When the men weren’t training, they were on sea search, spending ten hours a day patrol ing a wedge of ocean, looking for the enemy. It was intensely dul work. Louie kil ed time by sleeping on Mitchel ’s navigator table and taking flying lessons from Phil. On some flights, he sprawled behind the cockpit, reading El ery Queen novels and taxing the nerves of Douglas, who eventual y got so annoyed at having to step over Louie’s long legs that he attacked him with a fire extinguisher. Once, the gunners got so bored that they fired at a pod of whales. Phil yel ed at them to knock it off, and the whales swam on, unharmed. The bul ets, it turned out, carried lethal speed for only a few feet after entering the water. One day, this would be very useful knowledge.

One morning on sea search, Phil’s crew passed over an American submarine sitting placidly on the surface, crewmen ambling over the deck. Louie flashed the identification code three times, but the sub crew ignored him. Louie and Phil decided to “scare the hel out of them.” As Louie rol ed open the bomb bay doors, Phil sent the plane screaming down over the submarine. “The retreat from the deck was so hasty, it looked like they were sucked into the sub,” Louie wrote in his diary. “I gave the skipper an F for identification, but an A+ for a quick dive.”

The tedium of sea search made practical joking irresistible. When a loudmouth ground officer griped about the higher pay al otted to airmen, the crew invited him to fly the plane himself. During the flight, they sat him in the copilot’s seat while Louie hid under the navigator’s table, next to the chains that

linked the plane’s yokes to the control surfaces. When the officer took the yoke, Louie began tugging the chains, making the plane swoop up and down.

The officer panicked, Louie smothered his laughter, and Phil kept a perfect poker face. The officer never again complained about airmen’s pay.

Copilot Charleton Hugh Cuppernel . Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

Louie’s two proudest moments as a prankster both involved chewing gum. After Cuppernel and Phil swiped Louie’s beer, Louie retaliated by sneaking out to Super Man and jamming gum into the cockpit “piss pipe”—the urine relief tube. During that day’s flight, the cal of nature was fol owed by an inexplicably brimming piss pipe, turbulence, and at least one wet airman. Louie hid in Honolulu for two days to escape retribution. On another day, to get even with Cuppernel and Phil for regularly stealing his chewing gum, Louie replaced his ordinary gum with a laxative variety. Just before a long day of sea search, Cuppernel and Phil each stole three pieces, triple the standard dose. As Super Man flew over the Pacific that morning, Louie watched with delight as pilot and copilot, in great distress, made alternating dashes to the back of the plane, yel ing for someone to get a toilet bag ready. On his last run, Cuppernel discovered that al the bags had been used. With nowhere else to go, he dropped his pants and hung his rear end out the waist window while four crewmen clung to him to prevent him from fal ing out. When the ground crew saw the results al over Super Man’s tail, they were furious. “It was like an abstract painting,” Louie said later.

Phil’s remedy for boredom was hotdogging. After each day of sea search, he and another pilot synchronized their returns to Oahu. The one in front would buzz the island with wheels up, seeing how low he could get without skinning the plane’s underside, then goad the other into going lower. Phil hummed Super Man so close to the ground that he could look straight into the first-floor windows of buildings. It was, he said in his strol ing cadence,

“kind of daring.”

——

For each day in the air, the crew got a day off. They played poker, divvied up Cecy’s care packages, and went to the movies. Louie ran laps around the runway, keeping his body in Olympic condition. On the beach at Kahuku, he and Phil inflated their mattress covers, made a go at the waves, and nearly drowned themselves. Tooling around the island in borrowed cars, they came upon several airfields, but when they drew closer, they realized that al of the planes and equipment were fake, made of plywood, an elaborate ruse designed to fool Japanese reconnaissance planes. And in Honolulu, they found their Everest. It was the House of P. Y. Chong steakhouse, where for $2.50 they could get a steak nearly as fat as a man’s arm and as broad as his head.