Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (5 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

Considering the myriad influential factors at play, my belated discovery of my true generational status and family history should not be surprising. For decades, anti-Chinese immigration laws discouraged the immigration of Chinese women and retarded the development of family

life. Because of anti-Chinese sentiment, life under exclusion in America

necessitated a pact of silence among Chinese immigrants about their past.

And until recently, racial minorities and women were generally excluded

from written American history. Only since the civil rights movement,

the establishment of ethnic studies programs on college campuses, and

the current interest in cultural diversity have studies such as this one been

possible.

As the only in-depth study so far on Chinese American women, Unbound Feet fills the information void and restores Chinese women's rightful place in ethnic, women's, and American history, acknowledging their

indomitable spirit and significant contributions. More important, by

showing how Chinese American women were able to move from bound

lives in the nineteenth century to unbound lives by the end of World

War II despite the multiple forms of oppression they faced, this study

adds to the growing scholarship on women of color and the ongoing

debate about the workings and eradication of race, gender, and class oppression. Although Chinese American women have still not achieved

full equality, the important strides they made during a period of great

social change warrant careful study. It is my hope that Unbound Feet will

contribute to a more accurate and inclusive view of women's history,

and to a more complex synthesis of our collective past.

The absence of talent in a woman is a virtue.

A Chinese proverb

Feet are bound not to make them beautiful as a curved bow, but

to restrain the women when they go outdoors.

Nii'er-Ching (Classic for Girls)

When Great-Grandmother Leong Shee arrived in San

Francisco on the vessel China on April i5, 1893, she had with her an

eight-year-old girl named Ah Kum. When asked by the immigration inspector who the girl was, she said that Ali Kum was her daughter. The

story she told was that she had first immigrated to the United States with

her parents, was married to Chong [Chin] Lung of Sing Kee Company

in 1885, gave birth to Ali Kum in 1886, and then returned to China with

the daughter in 1889. When asked what she remembered of San Francisco, she replied in Chinese, "I do not know the city excepting the names

of a few streets, as I have small feet and never went out." Thirty-six years

later, when she was interrogated for a departure certificate, she denied

ever saying any of this.'

Great-Grandmother most likely had to make up the story in order to

ger her mui tsai, Ah Kum, into the United States. She was probably

afraid of being accused of bringing in a potential prostitute. Yet having Ah Kum was as much a status symbol as a real help for Leong Shee.

Allowing Ah Kum to accompany his wife was probably one of the concessions Great-Grandfather Chin Lung had made to entice her to join

him in America. While Chin Lung continued to farm in the SacramentoSan Joaquin Delta, Great-Grandmother chose to live above the Sing Kee store at 8o8 Sacramento Street, where she gave birth to five children in

quick succession. Even with Ah Kum's help, Great-Grandmother found

life in America difficult. Unable to go out because of her bound feet,

Chinese beliefs that women should not be seen in public, and perhaps

fear for her own safety, she led a cloistered but busy life. Being frugal,

she took in sewing to make extra money. As she told my mother many

years later, "Ying, when you go to America, don't be lazy. Work hard

and you will become rich. Your grandfather grew potatoes, and although

I was busy at home, I sewed on a foot-treadle machine, made buttons,

and weaved loose threads [did finishing work]."2

Great-Grandmother's secluded and hard-working life in San Francisco

Chinatown was typical for Chinese women in the second half of the nineteenth century. Wives of merchants, who were at the top of the social

hierarchy in Chinatown, usually had bound feet and led bound lives. But

even women of the laboring class-without bound feet-found themselves confined to the domestic sphere within Chinatown. Prostitutes,

who were at the bottom of the social order, had the least freedom and

opportunity to change their lives. Whereas most European women found

immigration to America a liberating experience, Chinese women, except in certain situations, found it inhibiting. Their unique status in

America was due to the circumstances of their immigration and the dynamic ways in which race, class, gender, and culture intersected in their

lives.

Passage to Gold Mountain

Few women were in the first wave of Chinese immigrants

to America in the mid-nineteenth century. Driven overseas by conditions of poverty at home, young Chinese men-peasants from the Pearl

River delta of Guangdong Province (close to the ports of Canton and

Hong Kong)-immigrated to Gold Mountain in search of a better livelihood to support their families. They were but a segment of the Chinese

diaspora and a sliver of the international migration of labor caused by

the global expansion of European capitalism, in which workers, capital,

and technology moved across national borders to enable entrepreneurs

to exploit natural resources and a larger market in undeveloped coun-

tries.3 According to one estimate, at least z.5 million Chinese migrated

overseas during the last six decades of the nineteenth century, after China was defeated in the Opium Wars (1839-4z; 1856-60) and forced open

by European imperialist countries to outside trade and political domination.' Except for the 250,000 Chinese who were coerced into slave

labor in the "coolie trade" that operated from 1847 to 1874, most willingly answered the call of Western capitalists, immigrating to undeveloped colonies in the Americas, the West Indies, Hawaii, Australia, New

Zealand, Southeast Asia, and Africa to live, work, and settle.

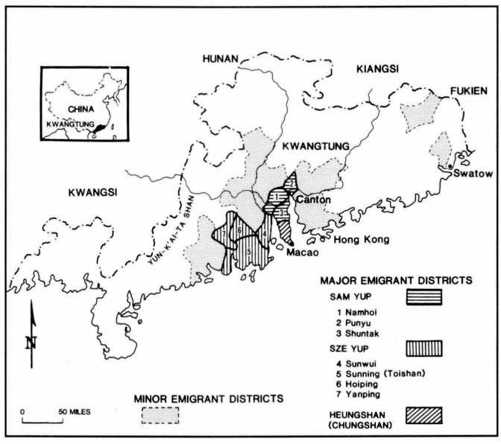

Kwangtung (Guangdong) Province: Emigrant Districts. SOURCE: Sucheng

Chan, This Bittersweet Soil: The Chinese in California Agriculture, 1860-1910

(Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986), p. 1g.

Peasants in the Pearl River delta in southeast China were particularly

hard hit by imperialist incursions. Aside from suffering increased taxes,

loss of land, competition from imported manufactured goods, and unemployment, they also had to contend with problems of overpopulation,

repeated natural calamities, and the devastation caused by the Taiping

Rebellion (185o-64), the Red Turban uprisings (1854-64), and the ongoing Punti-Hakka interethnic feud. Because of their coastal location

and their long association with the sea and contact with foreign traders,

they were easily drawn to America by news of the gold rush and by labor contractors who actively recruited young, able-bodied men to help

build the transcontinental railroad, reclaim swamplands, develop the fisheries and vineyards, and provide needed labor for California's growing

agriculture and light industries. Steamship companies and creditors were

also eager to provide them with the means to travel to America.5 Like

other immigrants coming to California at this time, Guangdong men

intended to strike it rich and return home.6 Thus, although more than

half of them were married, most did not bring their wives and families.

In any case, because of the high costs and harsh living conditions in California, the additional investment required to obtain passage for two or

more, and the lack of job opportunities for women, it was cheaper and

safer to keep the family in China and support it from across the sea.

The absence of women set the Chinese immigration pattern apart

from that of most other immigrant groups. In 18 50, there were only 7

Chinese women, versus 4,0 18 Chinese men, in San Francisco.? Five years

later, women made up less than z percent of the total Chinese population in Americas As merchant Lai Chun-chuen explained in response

to the anti-Chinese remarks of California Governor John Bigler:

It is stated that "too large a number of the men of the Flowery Kingdom have emigrated to this country, and that they have come alone, without their families." We may state among the reasons for this that the wives

and families of the better families of China have generally compressed

feet; they live in the utmost privacy; they are unusual to winds and waves;

and it is exceedingly difficult to bring families upon distant journies over

great oceans. Yet a few have come; nor are they all. And further, there

have been several injunctions warning the people of the Flowery land

not to come here, which have fostered doubts; nor have our hearts found

peace in regard to bringing families.9