Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (10 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

THE SHELTERED LIVES OF IMMIGRANT WIVES

Between 187o and 188o, the percentage of Chinese

women in San Francisco who were prostitutes had declined from 71 to

5o percent, while the percentage of women who were married had increased from approximately 8 to 49 percent, most likely owing to the

enforcement of antiprostitution measures, the arrival of wives from

China, and the marriage of ex-prostitutes to Chinese laborers. The number of wives continued to rise after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, when merchant wives became the prime category of

female immigrants from China. By the turn of the century, married

women made up 6z percent of the Chinese female population in San

Francisco. 88

Within the patriarchal structure of San Francisco Chinatown, immigrant wives occupied a higher status than mui tsai and prostitutes, but

they too were considered the property of men and constrained to lead

bound lives. Members of the merchant class, capitalizing on miners' and

labor crews' need for provisions and services, were among the first Chinese to come to California. They were also the only Chinese who were

allowed to and who could afford to bring their wives and families, or to

establish second families in America.89 In the absence of the scholargentry class, which chose not to emigrate, the merchant class became

the ruling elite in Chinatown, and their families formed the basis for the

growth of the Chinese American population and the formation of the

middle class.

Referred to as "small-foot" or "lily-feet" women in nineteenthcentury writings because of their bound feet, most merchant wives led

the cloistered life of genteel women. They generally had servants and

did not need to work for wages or be burdened by the daily household

chores of cooking, laundering, and cleaning. Rather, they spent their

leisure hours prettying up or creating needlework designs, to be used as

presents to distant relatives or as ornamentation for their own apparel

and that of family members. Sui Seen Far, a noted California writer in

the late nineteenth century, described their lives this way:

The Chinese woman in America lives generally in the upstairs apartments of her husband's dwelling. He looks well after her comfort and

provides all her little mind can wish.... She seldom goes out, and does

not receive visitors until she has been a wife for at least two years. Even

then, if she has no child, she is supposed to hide herself. After a child has

been born to her, her wall of reserve is lowered a little, and it is proper

for cousins and friends of her husband to drop in occasionally and have

a chat with "the family."

Now and then the women visit one another.... They laugh at the

most commonplace remark and scream at the smallest trifle; they examine one another's dresses and hair, talk about their husbands, their babies, their food; squabble over little matters and make up again; they dine

on bowls of rice, minced chicken, bamboo shoots and a dessert of candied fruits.90

At least one merchant wife in San Francisco Chinatown did not view

her life so positively, though. "Poor me!" she told a white reporter. "In

China I was shut up in the house since I was io years old, and only left

my father's house to be shut up in my husband's house in this great country. For seventeen years I have been in this house without leaving it save

on two evenings."" To pass her time, she worshiped at the family altar,

embroidered, looked after her son, played cards with her servant, or chatted with her Chinese neighbors. Periodically, her hairdresser would come

to do her hair, or a female storyteller would come to entertain her. Her

husband had also provided her with a European music box and a pet canary. Only through her husband, servant, hairdresser, and female neighbors was she able to maintain contact with the outside world.

Despite her wealth, she envied other women "who are richer than I,

for they have big feet and can go everywhere, and every day have something new to fill their minds." This woman, however, as she was well

aware, was still only a piece of property to her husband, always fearful

of being sold "like cows" if her husband tired of her, or of having her

son taken from her and sent back to China to the first wife. Also, as she

herself pointed out, she had few avenues of escape. Chinatown was governed by the laws of China, and the Mission Home could provide her

with only a temporary refuge. "I am too old for any man to desire in

marriage, too helpless in the ways of making money to support myself,

too used to the grand living my husband provides to be deprived of it."

In fact, however, such women of leisure were but a small proportion

of immigrant wives in the late nineteenth century. Most wives were married to Chinese laborers who, having decided to settle in America, had

saved enough money to send for a wife or to marry a local Chinese woman-most likely a former prostitute or American-born. As it was

for other working-class immigrant women, life for this group of wives

was marked by constant toil, with little time for leisure. Undoubtedly,

they were the seamstresses, shirtmakers, washerwomen, gardeners, fisherwomen, storekeepers, and laborers listed in the manuscript census.

Even those listed as "keeping house" most likely also worked for wages

at home or took in boarders to supplement their husbands' low wages.92

In addition to their paid work, they were burdened with child care and

domestic chores, which they had to perform in crowded housing arrangements. According to the San Francisco Health Officer's Report for

1869-70, "Their mode of living is the most abject in which it is possible for human beings to exist. The great majority of them live crowded

together in rickety, filthy and dilapidated tenement houses like so many

cattle."93 Five years later, the writer B. E. Lloyd noted in Lights and Shades

of San Francisco, "A family of five or six persons will occupy a single

room, eight by ten feet in dimension, wherein all will live, cook, eat,

sleep, and perhaps carry on a small manufacturing business."94 In 188o

the city's Board of Health condemned Chinatown as "a cancer-spot,

which endangers the healthy and prosperous condition of the city of San

Francisco. "95

Women doing laundry, San Francisco, i89os. (Charles Weidner photo, Judy

Yung collection)

Like peasant women in China, working-class wives in San Francisco

could freely go out to work, worship at the temple, or shop in the Chinatown stores that provided for all their needs. But they did not travel far from home or mingle with men. Even when they spent an occasional

evening at the Chinese opera, they would sit in a separate section from

the men. Nor did they linger long in the streets, so threatened were they

by the possibility of racial and sexual assaults. As reported in the Daily

Alta California:

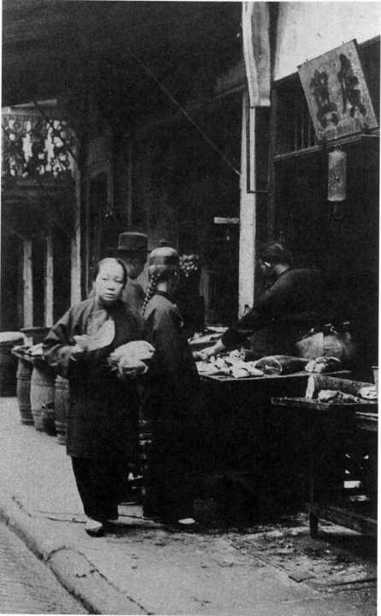

Shopping in San Francisco Chinatown, i89os. (Courtesy of Philip P. Choy)

Last evening, at the fire on Dupont street, a crowd of Waverly Place

loafers, and thieves, and roughs, who were being kept back from the fire

by the police, amused themselves by throwing a Chinawoman down in

the muddy street and dragging her back and forth by the hair for some

minutes. The poor female heathen was rescued from their clutches at last

by officer Saulsbury, and taken to the calaboose for protection. He also

arrested one of her assailants, who was pointed out by the woman, but

as she could not testify against him [Chinese could not legally testify

against whites] he was dismissed on his arrival at the calaboose.96

The safety of Chinese women could not be assured even in the company of white missionaries. According to the testimony of Rev. W. C.

Pond:

Under the protection of American ladies they [Chinese girls from the

Methodist mission] went out, one afternoon to walk. When at some distance from home, they were set upon by a gang of men and boys, pelted,

and then, as I understand, struck, their clothes rent, their ear-rings torn

from their ears, and when an Irish woman (God bless her!) gave them

refuge, her house was stoned.97

As it became more difficult to import Chinese prostitutes, Chinese

women found themselves the targets of kidnappers, sometimes in broad

daylight, to be sold into prostitution. During one week in February 189 8,

eight such kidnappings occurred.98

Unlike in China, where three generations often lived under the same

roof, the typical family structure in San Francisco Chinatown was nuclear, including a married couple, the husband about nine years older

than the wife, and one or two children.99 The family, however, remained

a patriarchal, economic unit. Within this structure, the husband worked

outside the home for wages, while the wife stayed home to perform unpaid housework and child care as well as paid piecework for subcontractors. Since the husband was the chief wage earner and the representative of the family on the outside, the wife was dependent on him

for subsistence and protection and thus remained in a subordinate role.

In this sense, their respective roles and gender relations were no different from those in preindustrial China. But the absence of the mother in-law, the scarcity of women, and the couple's common goal to survive

in a new and often hostile land were different circumstances that did begin to affect gender roles and relationships.

One of the advantages for women who immigrated to America was

the chance to remove themselves from the rule of the tyrannical motherin-law, the one position that allowed women in China any power. 100 Not

only was the daughter-in-law freed from serving her in-laws, but she was

also freed of competition for her husband's attention and loyalty and

given full control over managing the household. Because of the small

number of Chinese women, wives in America were valued and accorded

more respect by their men (although there were still incidences of wife

abuse). In addition, most Chinese men, because of their low socioeconomic status, could not afford a concubine or mistress, much less a wife.

Thus, having a wife was a status symbol to be jealously guarded. Women

physicians who attended Chinese wives and children had "much to say

of the kindness and indulgence of Chinese husbands, their sympathy

and consideration towards their wives in pregnancy and childbirth and

their willingness to spend money for pretty clothes for them."101 This

same indulgence is also evident in photographs taken in the 18 9 os that

show Chinese families in the streets of Chinatown or at the park.'°2

Wives were also more valued in America because they were essential

helpmates in the family's daily struggle for socioeconomic survival. As

it was for European immigrants, the family's interest was paramount,

and all members worked for its survival and well-being. A Chinese wife's

earnings from sewing, washing, or taking in boarders could mean the

difference between having pork or just bean paste with rice for dinner,

or between life and death for starving relatives back in China. It was also

her duty to cook and prepare the Chinese meals and special foods for

certain celebrations, to maintain the family altar, to make Chinese clothing and slippers for the family, to raise the children to be "proper Chinese," and to provide a refuge for the husband from the hostile world

outside. Thus, even while the family was a site of oppression for Chinese women in terms of the heavy housework and child care responsibilities and possibly wife abuse, it was also a source of empowerment.

Wives ran the household and raised the children; they also played an important role in the family economy and in maintaining Chinese culture

and family life as a way of resisting cultural onslaughts from the outside.

As Protestant women gained a foothold in bringing Christianity, Western ideas, and contact with the outside world into Chinatown homes,

Chinese wives became more aware of their bound lives. They also be came an important link between the Chinese family and the larger society and an influential factor in the education and socialization of Chinese American children. Convinced that there was little hope of redeeming the Chinese unless the women were converted to Christianity

and Americanized, missionary women visited Chinese homes regularly

to give lessons on the Bible and American domestic and sanitary practices, often while the women worked-"one woman making paper gods,

another overalls, another binding shoes."103 According to one missionary report in 1887, the visiting list was eighty-five families long, including one hundred children, thirty-six "little-footed" women, fifteen

"little-footed" girls, and about twenty-eight slave girls.104 Mothers, one

observer noted, were particularly interested in having missionaries provide their children with an education: