Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (37 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

Wong Shee Chan recalled similar hard times. Betrothed when ten years

old and married at seventeen to my great-grandfather Chin Lung's eldest

son, Chin Wing, she was admitted to the United States in 1920 as a U.S.

citizen's wife. They initially farmed land that Great-Grandfather had purchased in Oregon but, soon after, returned to San Francisco and worked

at Chin Lung's trunk factory on Stockton Street. In 193 z, Great-Grandfather decided to retire to China to avoid the depression, leaving what

business assets he had left to his sons. Chin Wing tried to maintain the

trunk factory, but to no avail. The family had to pawn Grandaunt's jewelry in order to make ends meet. "Those were the worst years for us,"

recalled Grandaunt, who by then had six children to support. "Life was

very hard. I just went from day to day." They considered themselves lucky

when they could borrow a dime or a quarter. "A quarter was enough

for dinner," she said. "With that I bought two pieces of fish to steam,

three bunches of vegetables (two to stir-fry and the third to put in the

soup), and some pork for the soup."52 For a brief period, while her husband was unemployed, the family qualified for federal aid; but after he

went to work as a seaman, Grandaunt was left alone to care for the children. She had to find work to help support the family. Encouraged by

friends, she went to beauty school to learn how to be a hairdresser. At

that time, there were sixteen beauty parlors in Chinatown-the only businesses in the community to be run by Chinese women.51 After she passed

the licensing examination, which she was able to take in the Chinese language, Grandaunt opened a beauty parlor and bathhouse in Chinatown,

working from 7 A.M. to I I r.M. seven days a week. She kept the children

with her at the shop and had the older ones help her with the work. Thus

she was able to keep the family together and make it through the depression.

Women across the country likewise found ways to "make do." When their husbands and sons became unemployed, many white women entered the labor market for the first time, finding work in female-dominated occupations-clerical work, trade, and services. In the decade between 1930 and 1940, the number of married women in the labor force

increased nearly 5o percent despite mounting public pressure that they

not compete with men for jobs. Often, in fact, it was not men who were

edged out of jobs by white women, but black women-particularly domestic workers-who were already at the bottom of the labor ladder. Concentrated in the marginal occupations of sharecropping, household

service, and unskilled factory work, black women suffered the highest

unemployment rate among all groups of women. 14 Most other workingclass women were able to keep a tenuous hold on their jobs in the industrial and service sectors even as their husbands became unemployed.

Women's marginal wages thus often kept whole families alive. Women

also learned to cut back on family expenditures, substituting store-bought

items with homemade products. They planted gardens, canned fruits and

vegetables, remade old clothing, baked bread, raised livestock, rented

out sleeping space, and did odd jobs. Pooling resources with relatives

and neighbors provided mutual assistance in terms of shared household

duties and child care. As a last resort, some women turned to prostitution. And among those who qualified, many went on relief 55

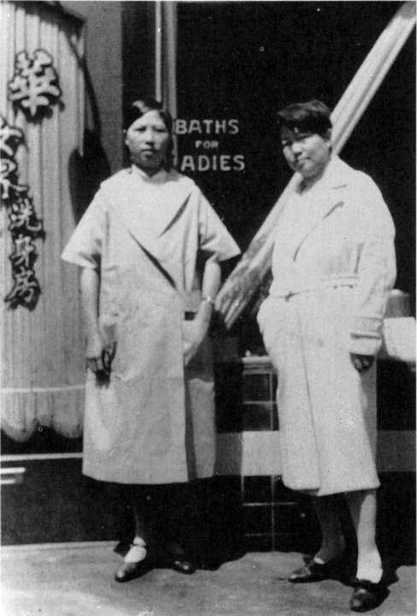

Grandaunt Wong Shee Chan (left) in front of her beauty parlor

and bathhouse in the 1930s. (Judy Yung collection)

It has generally been assumed that women also managed to provide

sufficient emotional support to keep the family together during these

troubled times. In 1987, however, Lois Rita Helmbold threw that assumption into question. After examining 1,340 interviews with white

and black working-class women in the urban North and Midwest that

were conducted by the Women's Bureau in the 193os, Helmbold concluded that a significant number of families were in fact torn apart by

the financial and emotional strains of the depression. The expectations

and actualities of female self-sacrifice resulted in unresolvable conflicts

between parents and children, husbands and wives; relatives, it is clear,

did not always come to the aid of unattached women. Family and marital breakups became widespread .,6 Moreover, as Jacqueline Jones points

out in her study on black women and the depression, federal aid to mothers with dependent children (started in 193 5) may have inadvertently

contributed to the disintegration of black families, for by "deserting"

their families, unemployed fathers enabled them to qualify for relief.

Jones's argument is supported by statistics: in the mid-193os, approximately 40 percent of all husband-absent black families received public

assistance; and by 1940, 31 percent of all black households had a female

head.57

In contrast, Chinese families held together. Whereas the nation experienced an increase in the divorce rate from the mid-1930s on, the

rate remained low among Chinese Americans. Chinese newspapers reported only nine cases of divorce in the 119 3 os, most of which were filed

by women on grounds of wife abuse, although three women also cited

lack of child support as a reason .18 No doubt, Chinese women experienced their share of emotional stress during the depression, but because of cultural taboos against divorce they found other ways to cope. My

grandaunt Wong Shee Chan recalled a number of occasions when her

unemployed husband took his frustrations out on her. "I remember buying two sand dabs to steam for dinner," she said. "Because he didn't like

the fish, he flipped the plate over and ruined the dinner for the entire

family. Even the children could not eat it then. See what a mean heart

he had?"59 Having promised her father that she would never disgrace

the Wong family's name by disobeying or divorcing her husband, she

gritted her teeth and carried on. But when the situation at home became

unbearable, Grandaunt would go to the Presbyterian Mission Home for

help. "She went there a couple of times, and each time it got ironed out

and she came home," recalled her eldest daughter, Penny.60 Jane Kwong

Lee, who was coordinator of the Chinese YWCA in the 1930S, noted

the added emotional stress that many women unaccustomed to accepting public assistance felt:

There is a family with a father, mother, and five small children. The

father was unemployed for several years before he obtained work relief.

The family is expressively grateful, for they are no longer afraid of starvation. Outwardly, the mother appears happy. Yet, when I talk with

her further, I can sense the struggle within her. She cannot bear the

thought of being on the relief roll. Her people in China think she is enjoying life here in the "Golden Mountain." She dares not inform

them about the family's sufferings and hardships. If she does, she would

"lose face." Although the relief money is enough to feed and clothe the

family, it is not sufficient to allow for better living quarters than the two

rooms they now occupy, without a private kitchen or a private bath. She

can afford no heat in the rooms even when the children are ill in bed.

This family is on the bare existence line. As in many other cases, at first

she felt humiliated about her surroundings. Later on, she got used to it.

Now she regards relief as a matter-of-fact.61

This pragmatic approach to life, kindled by personal initiative and a strong

sense of obligatory self-sacrifice in the interest of the family, helped many

Chinese immigrant women through the hardships that they faced in

America, including the depression.

The adverse impact of the depression was also blunted by the benefit that Chinese immigrant women and their families drew from federal

legislation and programs. Many of the New Deal programs discriminated

against women and racial minorities in terms of direct relief, jobs, and

wages. One-fourth of the NRA codes, for example, established lower

wage rates for women, ranging from 14 to 3 0 percent below men's rates. Relief jobs went overwhelmingly to male breadwinners, and significant

numbers of female workers in the areas of domestic service, farming,

and cannery work were not covered by the Fair Labor Standards Act or

Social Security Act. Black, Mexican, and Asian women who were concentrated in these job sectors were thus denied equal protection from

labor exploitation and access to insurance benefits. Moreover, under federal guidelines, Mexican and Asian aliens could not qualify for WPA jobs

and were in constant fear of deportation.62 Nevertheless, considering

their prior situation, Chinese women had more to gain than lose by the

New Deal. For the first time, they were entitled to public assistance. At

least 350 families were spared starvation and provided with clothing,

housing, and medical care to tide them over the depression. In addition,

more than fifty single mothers qualified for either Widow Pension Aid

or Aid to Dependent Children.63 The garment industry-which employed most of the Chinese immigrant women-was covered by the

NRA. At the urging of the International Ladies' Garment Workers'

Union (ILGWU), sweeps through Chinatown were periodically made

to ensure the enforcement of the new minimum-wage levels, work hours,

banned child labor law, and safety standards.64 NRA codes, however, were

insufficient to change sweatshop conditions in Chinatown, as employers circumvented or nullified the imposed labor standards through

speed-ups and tampered records. Only when workers took matters into

their own hands, as in the case of the 193 8 National Dollar Stores strike,

were employers forced to comply with federal labor laws.

The New Deal did have a positive impact on the living environment

of Chinese families. A 19 3 5 study of Chinatown's social needs and problems sponsored by the California State Emergency Relief Administration

(CSERA) indicated that housing was woefully substandard, playground

space and hours of operation inadequate, and health and day child care

sorely lacking.65 Federal programs, staffed by Chinese American social

workers in cooperation with churches and community organizations,

were instituted to deal with these specific problems. Families were

moved out of tenement houses to apartments and flats close by. Playground hours were extended and street lighting improved. Immigrant

mothers learned about American standards of sanitation and nutrition,

particularly the importance of milk in their diet, and had access to birth

control and health care at the newly established public clinic in the community. They were also entitled to attend English and job-training classes

and, as in the case of Law Shee Low, enroll their children in nursery

school. As a result, not only did some immigrant women receive direct relief, but their overall quality of life was somewhat improved by the New

Deal.

Although in many quarters of the nation the issue of working wives

was controversial, it was not a problem in San Francisco Chinatown,

where wives and mothers had always had to work to help support their

families. On the contrary, as their economic and social roles expanded

and their families grew increasingly dependent on them during the depression, the community's attitude toward working women took a turn

for the better. According to the 1935 survey conducted by CSERA,

women's place in the work world outside the home was no longer questioned:

The Chinese women of today are much more fortunate and certainly

more independent than they were ten or twenty years ago. They are now

permitted by their husbands to work outside their homes and the fear of

mockery by their neighbors has ceased since it has become the vogue to

work, whether to help out the family finances or to have a little pin money.

Generally speaking, to help the family finances, since most of them are

hard pressed.66

Gender relations also improved in their favor, as reflected in newspaper

reports. In 1933, for instance, the Chinese Six Companies sided with a

widow whose relatives were trying to rob her of her inheritance and force

her to marry a man of their choice.67 CSYP published articles appealing

to husbands to treat their wives better: "Don't be a tyrannical lord over

her, but respect her opinions, speak to her gently, and involve her in all

your affairs."68 In another editorial, after praising Jane Addams's exemplary work with the poor and her involvement with the women's and

peace movements, the newspaper encouraged the modern Chinese

woman to be aware of her rights, become physically fit, satisfy her domestic duties, attend to the children, and serve the community.69

Jane Kwong Lee was one of the few Chinese women who fulfilled

this role of the modern woman in the 19 3 os. After becoming the mother

of two and upon graduation from Mills College, she decided to go back

to work, even though her husband still had his meat market in Oakland.

"To stay home and take care of my children was, of course, my primary

concern," she wrote in her autobiography, "but in the midst of the depression period, it was necessary for me to seek employment."70 Unable

to find work in white establishments because of racism, Jane finally secured a part-time job at the Chinese YWCA, at a time when bilingual

community workers were sorely needed. It was her responsibility to make home visits and to provide assistance to immigrant women regarding immigration, health and birth control, housing, domestic problems, and

applications for government relief. Until she was offered a full-time job

as coordinator two years later, she also taught at a Chinese school in the

evenings. How did she manage it all?