Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (27 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

Initially, second-generation women's occupations were not very different from those of their immigrant mothers. The z goo and 1910 manuscript censuses indicate that Chinese women in San Francisco, whether

immigrant or native-born, worked as either prostitutes or seamstresses.

By igzo, however, as increased numbers of the second generation became better educated and more Americanized, their work pattern was

taking a path distinctly different from that of their mothers. They began to branch into clerical and sales jobs (see appendix table 6). As Rose

Chew, a social worker and second-generation woman herself, observed

in 1930, whereas immigrant mothers worked primarily in garment and

shrimp factories, did hemstitching and embroidery work, and served as

domestic day workers, daughters were working outside the community

as waitresses, stock girls, and elevator operators. Within the community,

a few were now employed as public school teachers, doctors, dentists,

bank managers and tellers, nurses, and beauty parlor owners.66

Although their work lives were an improvement relative to the

drudgery and low wages of their parents, many of the second generation were disappointed by America's false promises of equal opportunity. They had studied hard in school, but despite their qualifications

they were not given the same consideration in the job market as white

Americans. College placement officers at both the University of California, Berkeley, and Stanford University, for example, found it almost

impossible to place the few Chinese or Japanese American graduates there

were in any positions, whether in engineering, manufacturing, or business. According to the personnel officer at Stanford,

Many firms have general regulations against employing them; others object to them on the ground that the other men employed by the firms

do not care to work with them. Just recently, a Chinese graduate of Stanford University, who was brought up on the Stanford campus with the

children of the professors, who speaks English perfectly, and who is thoroughly Americanized, was refused consideration by a prominent California corporation because they do not employ Orientals in their offices.67

Occupational opportunities for American-born Chinese women were

further circumscribed by gender. Economic pressures at home often

forced girls to curtail their education and enter the labor force, where they worked at the same menial, low-wage jobs as their immigrant mothers. Domestic work was one such option. Protestant missionaries particularly encouraged Chinese girls to pursue this line of work because it

prepared them for their future role as homemakers. They also regarded

domestic work as "honest toil," unlike service in tearooms, restaurants,

and clubs that "leads to many serious dangers for young and attractive

Oriental girls."6s Here again, missionary women were imposing their

Victorian moral values on Chinese women. Although great care was

taken to place Chinese women in "respectable" Christian homes, many

were unhappy in these positions, complaining about the low pay, heavy

workload, intrusive supervision, and rude condescension they experienced on the job. Unlike Japanese women, few Chinese women wanted

to make a career out of domestic work.69

Compared to second-generation European American women, who

were finding upward mobility in office and factory work, Chinese American women were not doing as well. When they tried to compete for office jobs outside Chinatown, they were generally told, "We do not hire

Orientals," or "Our white employees will object to working with you."

In many cases white establishments that hired them did so only to exploit their "picturesque" appearance or their bilingual skills in Chinatown

branch offices. According to the sociologist William Carlson Smith,

Chinese or Japanese girls on the Coast have been employed in certain

positions as "figure-heads," as they themselves termed it, where they were

required to wear oriental costumes as "atmosphere.". . . A merchant on

Market Street in San Francisco said of the Chinese girls: "They dress in

native costumes, they attract attention, and they can meet the public. That

is why many of them are working as elevator girls and salesladies in big

department stores, some as secretaries and others in clerical positions. One

girl is a secretary in a radio station and she, too, wears Chinese dress."70

Gladys Ng Gin and Rose Yuen Ow are examples of Chinese American women who were willing to work in teahouses, restaurants, stores,

and nightclubs as "figure-heads." Their stories shed light on how

second-generation women were able to use the stereotyped images of

Chinese women in mainstream culture to their advantage. Although they

recognized that they were being used as "exotic showpieces," young

women like Gladys and Rose took the jobs because there were few

positions open to them that paid as well. In most cases they were temporary jobs, because once the novelty wore off the women were usually

let go.

Although American-born, Gladys was practically illiterate in English

as well as Chinese, her education having been interrupted when she was

taken to China as a young girl. She therefore considered herself "lucky"

when she found work as an usher at a downtown theater upon her return from China in 1918. She was only fifteen and did not know how

to speak English. It didn't matter, she said, because all they wanted her

to do was read numbers and take people to their seats. The one requirement was that she wear Chinese dress. For six months she was quite

happy, because despite the trouble of constantly having to wash and

starch the white Chinese dress she had to wear, she was making good

money. But gradually, she and the twelve other girls were laid off one

after another. In 192-6, after Gladys learned English, she got a job running an elevator at a department store downtown. Again she was required to wear Chinese dress, but the hours and wages were equally good,

so she was willing to tolerate the inconvenience. "Worked nine to six,

six days a week," she said. "Seventy-five dollars a month was very good

then. I was considered lucky to have found such a see mun [genteel] job."

This time she stayed on the job for over ten years.71

Rose Yuen Ow, whose parents were quite open-minded (in spite of

strong objections from relatives, her mother dressed her in Western

clothes, refused to bind her feet, and allowed her to attend public school

until she reached the eighth grade), was among the first in her generation to work outside the home in rgo9. She recalled facing more discrimination in the Chinese community than in the outside labor market. "The first place I worked at in Chinatown was a movie house," she

said. "I sat there and sold tickets. The cousins immediately told my father to get me home." She was about fourteen or fifteen years old then,

and her father paid no attention to this meddling. In 19 13, when she

went to work at Tait's Cafe, a cabaret outside Chinatown, handing out

biscuits and candy before and after dinner, "everyone talked about me

and said I worked and roamed the streets." Men would even follow her

to work from Chinatown to see where she was going. But despite what

people in the community said about her, her father permitted her to continue working at the cabaret. Like Gladys, she was required to wear Chinese dress to provide atmosphere; otherwise, it was an easy job. And she

was earning good money for the time-$5o a week.72

Rosie later moved up the wage ladder by capitalizing on mainstream

America's interest in Chinese novelty acts. Chinese performers who sang

American ballads and danced the foxtrot or black bottom were popular

nightclub acts in the 192os and 193os. Billed as "Chung and Rosie Moy," Rose and her husband, Joe, performed in the Ziegfeld Follies and in

big theaters across the country with stars such as Jack Benny, Will Rogers,

and the Marx Brothers. While the interest lasted, Rose earned as much

as $zoo to $30o a week. She would never earn that much money again.

With the exception of Anna May Wong, few Chinese American entertainers ever made it big in show business. Despite their many talents,

racism prevented them from making a profitable career out of it.

The double bind of sexism within the Chinese community and racism

in the larger society also made it difficult for women who tried to enter

and succeed in the business and professional fields. When white firms

did hire Chinese American women, it was usually for the purpose of attracting Chinese business to their branch offices in Chinatown. Such was

the situation for Dolly Gee, who had to fight both race and sex discrimination in order to establish a career in banking. At a time when

there were few business opportunities for women in Chinatown, Dolly

was regarded by her contemporaries as an exceptionally successful career woman. With the help of her father, Charles Gee, a prominent

banker, she got her first experience working at the French American Bank

in 19 14 at the young age of fifteen. As she told the story, her father was

initially hesitant to recommend her for the job because she was female:

Early in 1914 I heard him say that another bank, the French American,

desired to expand its savings activities and that there was a need for such

a service in Chinatown. He said it was a fine opportunity for a young

man, and regretted he had no son ready to take it up and follow in his

footsteps as a banker. I immediately pointed out that although he had no

son old enough, he had an energetic and ambitious daughter. I could see

no reason why I could not take on the job and bring credit to my house,

and he could advance no reason against it that I would listen to.73

When Dolly was introduced to the head of the bank, he raised objections to both her age and her gender. "I am surprised that you would

consider allowing your daughter to go to work, like a common laborer,"

the bank manager said. "In two or three years she should be married,

according to your custom." "It's true she is only fifteen years old," replied

her father. "But you'd better take her on. I'll never hear the last of it if

you don't. If she fails, it will be out of her head and no harm will be

done." That challenge drove Dolly to prove herself. She canvassed Chinese households and refused to budge until she got an account or two

from each family. She later recalled:

Naturally I met opposition because of my sex and my youth. This was

before the [Second] World War, remember, before even American girls had invaded the business world to any significant extent. But I did get

accounts, even among horrified elders who shook their heads at me while

shelling out. Second-generation Chinese, born in this country, were more

amenable.74

In 1923, when the French American Bank opened a branch in Chinatown, Dolly became the manager. And in 1929, when the bank merged

with the Bank of America and the branch office moved to a new location, she was retained as manager. She hired an all-female staff of bank

tellers to work under her and operated on the principles of trust and

personal service to the Chinese community. As the first woman bank

manager in the nation, Dolly Gee built "a brilliant record for herself in

banking," according to one corporate publication.75 Despite her abilities to draw deposit accounts and run an efficient branch, however, she

was never promoted to a higher position outside Chinatown.

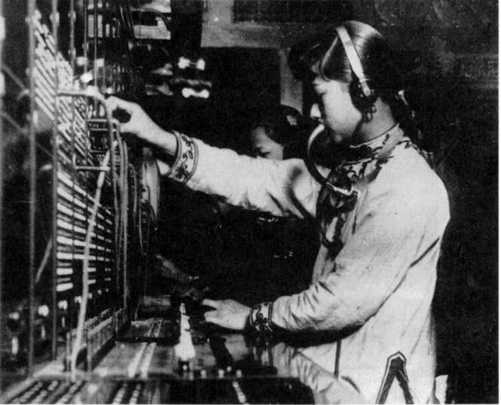

Unable to find jobs except in Chinatown, many Chinese American

women who were high school graduates and bilingual worked as clerks

and salespersons in local gift shops and businesses. Although these jobs

were better-paying and more prestigious than domestic work, they seldom compensated women for their education and skills or led to higher

positions of responsibility. Women who worked at the Chinatown Telephone Exchange, for example, had to know not only English but also

five Chinese dialects and subdialects, memorize 2,200 phone numbers,

and handle an average of 13,000 calls a day. 76 Until the 1906 earthquake

led to the rebuilding of Chinatown, only male operators had been employed at the Chinatown Exchange. Because of the low pay and customer complaints about the men's gruff voices and curt manner, however, they were replaced by women, who had more pleasant voices and

accommodating ways-and who, when dressed in Chinese clothing, also

proved to be tourist attractions. In the 19 zos, telephone operators, working eight hours a day, seven days a week, earned only $4o a month, compared to $ 5 o a month earned by housekeepers and $ 6o a month by clerks

and stock girls. Yet the limited number of jobs open to them and the

family atmosphere of their work environment both still made employment as a telephone operator desirable for second-generation women.77

Indeed, Chinese telephone operators were grateful for their jobs and seldom complained about the dress code or the working conditions, which

other female operators deemed unsatisfactory.78

The few college graduates who had professional degrees also found

themselves underemployed and confined to Chinatown because of

racism in the larger labor market. Many an engineer and scientist ended up working in Chinese restaurants and laundries. As was true for black

professionals, white employers would not hire them, and white clients

would not use their services.79 When Jade Snow Wong went to the college placement office for help, she was bluntly told, "If you are smart,

you will look for a job only among your Chinese firms. You cannot expect to get anywhere in American business houses. After all, I am sure

you are conscious that racial prejudice on the Pacific Coast will be a great

handicap to you."80 Later, frustrated by the limited role of a secretary,

she sought advice from her boss about a career change and discovered

that Chinese American women like her also had to contend with sexism. Her boss said,

Operator working the switchboard at the Chinatown Telephone Exchange,

19 20S. (Courtesy of the Telephone Pioneer Communications Museum)