Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (22 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

To sum up, it may be said that on the road of assimilation, the nativeborn Chinese have gone much farther than the Chinese of early days.

They have been Americanized to such an extent that their relatives in

China may find little in common with them. But the native-born Chinese are not completely assimilated, for they still have race-consciousness.3

Despite the insurmountable barriers, some Chinese Americans continued to push in that direction, while others became resigned to their

second-class status. Most, however, moved toward accommodationmaking the best of the situation until social conditions changed.

In their efforts to take the first steps toward breaking the double

binds of sexism at home and racism on the outside, to define their own

ethnic and gender identity, second-generation women were greatly influenced by Chinese nationalism, Christianity, and acculturation to

American life. As their stories demonstrate, the ideals of women's

emancipation that were embedded in the Chinese nationalist movement

encouraged parents to educate their daughters, allow them to work outside the home, engage in free marriage (as opposed to arranged marriage), and become politically active for the sake of a stronger and more

modern China. Christianity reinforced many of these same values. By

emphasizing female identity, independence, education, and spiritual

equality, Protestant institutions such as the YWCA drew Chinese girls

and women into the public sphere, familiarized them with Western customs and beliefs, and encouraged them to participate more actively in

civic affairs. Public schools and the mass media further instilled in them

the values of individuality, equality, and freedom as well as the desire for

the good life, characterized by fashionable clothes, romantic affairs,

sports, jazz, moving pictures, partying, and the like. However, as second-generation women tried to become Americanized, their newly

adopted lifestyle often clashed with their cultural upbringing at home.

Cultural Upbringing at Home

As children, most Chinatown girls led sheltered lives following Chinese traditions. Their mothers usually taught them to follow

the "three obediences and four virtues" and groomed them to become virtuous wives and mothers. Daughters growing up in the early 19oos

were expected to give unquestioning obedience to their parents and remain close to home, where they helped their mothers with incomegenerating work, shopping, and housework. Nurtured in Chinese culture, they spoke Chinese, ate Chinese food, and celebrated Chinese

holidays. Although sons were still favored over daughters, girls were often more valued in America than in China because of their scarcity and

the increased opportunities available to them. Moreover, Christian doctrine and Chinese nationalist ideology both advocated women's rights

and, together, influenced social attitudes toward the value and upbringing

of girls, especially among middle-class families. A comparative look at

the early years of Alice Sue Fun and Florence Chinn Kwan, both of

whom grew up in San Francisco Chinatown in the i9oos, shows how

these factors affected the cultural upbringing of Chinese American girls.

Given the working-class background of most Chinese families in San

Francisco at this time, Alice's story is the more representative of the two.4

She was only seven years old when she lost her father because of the

19o6 earthquake and fire. Forced to evacuate their home in Chinatown,

the family moved across the bay to Oakland, where they lived in a

makeshift tent. "My father dug clams and got sick eating them," Alice

recalled. "Contaminated water, you know. So he died soon after of typhoid fever. That was in September. My sister was born four days after

my father died." Alice's mother decided to move her six children back

to San Francisco Chinatown. A year later, she remarried.

While her stepfather worked as a cook, her mother supplemented the

family income by sewing at home. When she was eight, Alice began attending the Oriental Public School from 9:oo to 2.:3o and True Sunshine Chinese School from 2-:3o to 5:oo. Then she would come home

and help with the housework and take care of her younger brothers and

sisters. "I was the one who sewed their clothes, using those old foottreadle machines. Everything was used. I would take an old shirt apart

and repiece it together for Little Brother's trousers." Because her mother

followed tradition and rarely left the house, it also fell on Alice to do

the shopping. Both of her parents were very strict. When she misbehaved, her mother would punish her with a linggok (a knuckle-rap on

the head) or, worse, with a switch, hitting her "until flower patterns [black

and blue marks] broke out." Alice particularly resented the lack of freedom of movement:

It wasn't easy. Mother watched us like a hawk. We couldn't move without telling her. When we were growing up, we were never allowed to go

out unless accompanied by an older brother, sister, or somebody else....

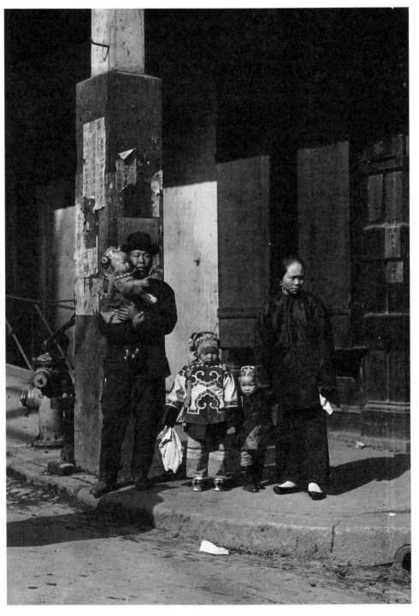

Alice Sue Fun (center) with (from left to right) Uncle holding Harris, Elsie,

and Mother during Chinese New Year, 1904. (Arnold Gcnthe photo;

courtesy of Library of Congress)

If you wanted to go shopping, you might as well forget it because, one

thing, you didn't have any money. Secondly, you knew your mother

wouldn't let you go, so what's the use of asking, right?

There was little time for play, but Alice had fond memories of Chinese celebrations, the Chinese opera, embroidery classes at the Congregational church on Saturdays, and the 19 15 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Although Alice attended church on Sundays, her

mother preferred to worship her Chinese gods at home. She also brewed

Chinese herbs whenever anyone became sick, cooked all the special dishes

during the Chinese holidays, related legendary stories associated with

the holidays as well as scary ghost stories, and took the children with her

whenever she went to the Chinese opera.

In the old days, there were two operas a day. It cost a little over a dollar

for the grand admission ticket, but after nine o'clock the admission would

be lowered to twenty-five cents. Free for children if accompanied by an

adult. Everyone ate and talked during the opera. It was quite festive.

That's how I learned to love the opera.

In this way, Alice grew to appreciate her Chinese cultural heritage. The

highlight of her childhood was the 19 15 International Exposition held

in San Francisco to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal and the

rebirth of the city following the earthquake. "It was once in a lifetime

and we saved to go see the fair. For about twenty cents a day you could

spend the whole day there. There were so many things to see, but I was

always partial to the Chinese exhibits," she said.

When Alice turned fifteen, her mother decided that was enough education for a girl and that Alice should help the family out.' Alice found

a sales job at the Canton Bazaar and gave half her earnings-$25 a month

in gold pieces-to her mother. Experiencing a degree of freedom and

economic independence, she decided to strike out on her own. Against

her mother's wishes, she married her Chinese teacher, whom she described as "poorer than a church mouse," and moved to New York. When

her marriage failed, she left her husband and traveled around the world

as maid and companion to the actress Lola Fisher. "She treated me very

well," said Alice. "Working those few years with Miss Fisher educated

me, broadened my outlook, and made a different person out of me." As

she had deeply resented her sheltered and strict upbringing, she especially appreciated the opportunity the job gave her to travel, to go beyond her mother's limited world. Years later, she compared her life with

that of her mother in this way:

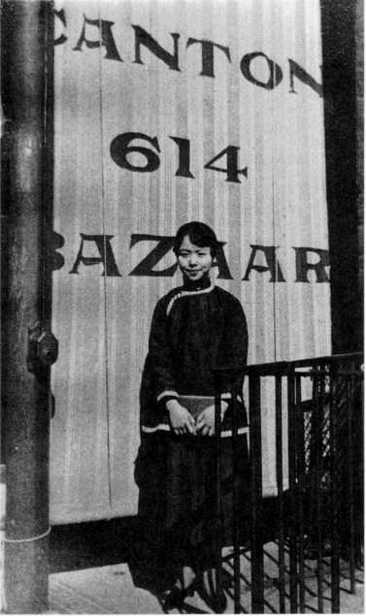

Alice Sue Fun at the Canton

Bazaar, where she worked as a

salesgirl in 19 15. (Courtesy

of Alice Sue Fun)

My mother lived a very sheltered life. Even up to her old age, she never

trusted herself to go out alone. She was afraid that she'll get lost. And

then she didn't like to exercise a lot, or walk a lot.... I would go out

anytime I want and anywhere I want. Even in foreign countries, I

wasn't afraid to go out alone. In Hong Kong, I went exploring all over

on the bus.... I like to be independent. I don't like to always be accompanied by people. I guess I had enough of that when I was a young

girl.

Whereas Alice was raised according to Chinese tradition, Florence

Chinn Kwan faced fewer restrictions growing up in San Francisco Chinatown because of the liberal middle-class background of her parents.

Her father was a missionary teacher who had come to the United States

when he was twelve years old. He later returned to China to marry and

was able to bring his wife back to America. Both parents were highly nationalistic toward their homeland and modern in their chosen lifestyle.

After the 1911 Revolution, her father was among the first to cut his

queue; her mother, to unbind her feet; and both, to allow their daughter to appear as a princess in the parade that celebrated the founding of

the new republic. Whereas Alice always dressed in Chinese-style clothes,

Florence wore Western dresses. "My father didn't want me to wear Chinese clothes. He said he didn't want people staring at me and saying

you're Chinese, you're not American," she explained.6 Although she,

too, was not allowed to go out alone, her parents were not as strict as

Alice's. Her father took her along on his daily walks to the park, and often downtown or to Chinatown to shop. Also unlike Alice, she was rarely

physically punished. The only time it happened was when she slid down

a bannister and broke her front teeth.

Pauline Fong Woo (left) and

Florence Chinn Kwan (right) as

flower girls in 19o8. (Courtesy

of Florence Chinn Kwan)

While Alice described her parents as uneducated, hard-working,

strict, and distant to their children, Florence remembered her father as

gentle, honest, and devout. "He would hold me on his lap while reading in his study. He was quite artistic and used to draw pictures for me

when I was a child." Her mother was patient, alert, and humble, with a great capacity for learning. Like Alice's mother, she sewed at home to

supplement her husband's income. But as Florence recalled, she was also

quite active outside the home. Aside from starting the Women's Missionary Society at the Chinese Congregational church, "she was always

helping the sick and the needy by going to their homes, cooking for them

and caring for them all without compensation."7