Two Rings (6 page)

Authors: Millie Werber

The Germans never came looking for my father, as far as I know. They did come for my uncle, though. It was the next year, and they went rampaging through the ghetto, banging on people's doors, arresting those with socialist affiliations.

The Germans had already conducted oblavas for other groups. The intelligentsia, the doctors, and the butchers and water carriers, too, maybe because, either through education or brute strength, these men could be trouble if they organized resistance groups. But on this day, the Germans came looking for the leftists, and the soldiers came into our building looking particularly for my uncle, my Feter, Yisroel Glatt.

The Germans had already conducted oblavas for other groups. The intelligentsia, the doctors, and the butchers and water carriers, too, maybe because, either through education or brute strength, these men could be trouble if they organized resistance groups. But on this day, the Germans came looking for the leftists, and the soldiers came into our building looking particularly for my uncle, my Feter, Yisroel Glatt.

“Glatt! Where is Yisroel Glatt?” they screamed, angry already.

They had lists of names. I suppose their informers had told them thingsâwho belonged to which organization, who perhaps was trying to stash what where. They burst into our building, clutching their lists, pounding through the hallways with their heavy boots, calling out the names of those they were looking for.

Â

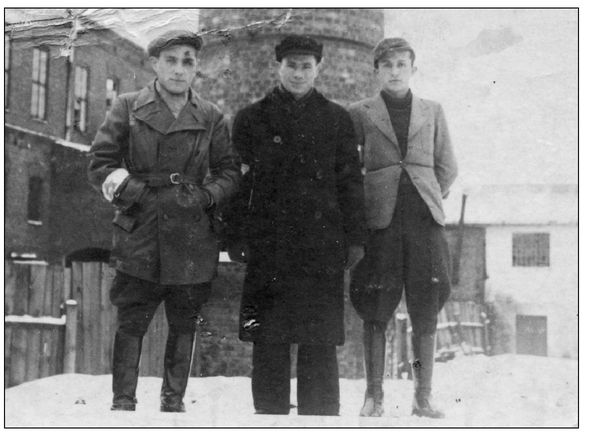

Feter, center, and friends

They banged on our door.

“Glatt. We're here for Yisroel Glatt.”

I knew what they could do. I knew what these soldiers were capable of. Even on a whim, even just for fun.

Some time before, early on in the war, perhaps in September or October 1939, the soldiers had come for Majer Berger, a Torah scribe who lived in our building. He was a quiet man with gentle eyes that creased at the corners when he smiled at me and a light red beard stained murky yellow in placesâfrom cigarettes, I suppose, though I never saw him smoke. He had four small boys; I guess he was in his forties, but I was just twelve at the time, and he seemed ancient to me, the very essence of a religious man. I'm sure he was pious; I probably thought he was close to sacred.

When the Germans came for him, he offered no resistance. I didn't even know until late in the day that he had been taken. When he returned later in the evening, I saw him in the hallway. He walked slowly, pressing his hand against the wall for support. A good part of his beard was gone and his face was smeared with blood. Mama pulled me into the apartment, wanting to shield me from such sights. The next day, I learned the story from others in the building: The Germans had taken Mr. Berger and two other bearded Jews down to the Jewish high school at 27 Żeromskiego Street. They lined up the men by a tree and then, one by one, grabbed bits of their beards and yanked the hairs out from their bleeding chins. Just like that, the soldiers pulled out the beards of these harmless men. Then the men were made to climb the tree and balance

themselves on the branches. The soldiers ordered them to yell out “cuckoo” to each other, obedient show-birds put on display. The Germans were suitably entertained, gawking at the men, laughing and joking as Mr. Berger and the two others tried not to fall. After a time, the men were permitted to come down from the tree and return to their homes.

themselves on the branches. The soldiers ordered them to yell out “cuckoo” to each other, obedient show-birds put on display. The Germans were suitably entertained, gawking at the men, laughing and joking as Mr. Berger and the two others tried not to fall. After a time, the men were permitted to come down from the tree and return to their homes.

How is a young girl to understand the meaning of an event like this? A child understands schoolyard meanness, classroom mischief. Jack once told me that when he was a boy and was made to study with some very old and, he said, very smelly rabbi who had a tendency to nod off during their lessons, he and some of the other boys in the class would sometimes glue little bits of the rabbi's beard to the study table as he slept. The boys would get a laughâand a good hard smackâwhen the rabbi awoke. Little Jewish boys, studying Talmud, playing at pranks.

Â

Me, circa 1935

But thisâwhat happened with Mr. Bergerâwas something else. There was blood and, in Mr. Berger's eyes, a confused look that I didn't understandâbewilderment and fear and defeat all at once. I stared, a young girl in braided pigtails, cowering in my mother's arms.

When they came for my uncle, I thought of Motel Rafalowitz and old Majer Berger, and again I was scared.

The Germans didn't find Feter that dayâhe was still in Russia at that point and returned only a few months later after he realized he wouldn't be able to arrange for his family's transport. But not finding my uncle just seemed to anger the soldiers more. They stormed down the hall and banged on the door of another family. Here, too, lived a man named Glatt, but not my uncle, not any relation of his, and not, as far as any of us knew, involved in the Left Po'alei Zion or any other socialist group. Nonetheless, his name was Glatt. The Germans had Glatt on their list, and they were determined to get a Glatt.

This Glatt they found, and they grabbed him out of his apartment, his family screaming, “Please, please, don't take him,” Glatt himself trying to tell them they had the wrong man. It was useless to plead; it was useless to cry.

They shot him in the hall.

I remained with Mama in our room, trying not to hear.

When the German army put up a flyer in the ghetto announcing that Jews aged fifteen to forty could register for work at the Steyr-Daimler-Puch factory just outside of town, I didn't want to go. It was the summer of 1942, and although the ghetto was dreadful to me, I barely ever wanted to venture out of the cramped room we shared. I was determined never to leave my family. Everything seemed so precarious in the ghetto. I didn't trust that anything would stay in place if I didn't watch it all the time. If I went away to work and live at the factory, what would be left when I returned?

I didn't want to go.

It was my uncle, my Feter, who made me. He had returned from Russia by this time and was adamant that all of us try to find work. “If you work,” he said, “you might live.”

My brother had been chosen for work as a street sweeper. Majer had already studied at a private Jewish high school, which was a big honor in those days; if you could graduate from high school and get your

matura

âthat was considered the mark of a truly educated man. But in the ghetto, work of any kind was precious, and he had been relieved to have a job. One day, though, as he was sweeping the street, he was knocked over by German soldiers driving by in a truck. They were laughing, he told me, pleased that they had run down a Jew. He broke his leg in the fall. Mama tried to set it straight, but he walked with a limp after that.

matura

âthat was considered the mark of a truly educated man. But in the ghetto, work of any kind was precious, and he had been relieved to have a job. One day, though, as he was sweeping the street, he was knocked over by German soldiers driving by in a truck. They were laughing, he told me, pleased that they had run down a Jew. He broke his leg in the fall. Mama tried to set it straight, but he walked with a limp after that.

When the factory announced that they would take Jewish workers, Majer couldn't goâthey wouldn't take anyone they considered disabled. My father and aunt and uncle had already managed to get jobs: My father worked in the Kromolowski factory, where they made saddles, Feter worked in a tannery,

and Mima was a seamstress in a shop where she made and mended clothes for the Germans. But Mama and I needed work, and even though she was over forty, Mama said she would go with me to the munitions factory to register.

and Mima was a seamstress in a shop where she made and mended clothes for the Germans. But Mama and I needed work, and even though she was over forty, Mama said she would go with me to the munitions factory to register.

It didn't take long for the Germans to sort through the many people who showed up. I was accepted without question; I was young, thin, and delicate, but in apparent good health. At forty-three, Mama was too old. They wouldn't take her. She was sent back to the ghetto, and I was left at the factory, alone.

I wanted desperately to go with her, to return to the ghetto and stay with her and the rest of our little family. I wanted to be able to sleep beside her, to feel her warmth surround me. Always that, maybe mostly thatâthe warmth of Mama's ample body in the night. Despite the oblavas, the unprovoked brutalities, the sickness and the hunger and the dread that were upon me, still, I wanted only to be with Mama in the ghetto.

Yet I was not allowed. I was made to stay at the factory. Feter said, and the family agreed, if you work, you might live. So, at fifteen, I began to work in the ammunitions factory, and after that first day at work, I never spent another night with my mother again.

The factory was a large building a couple of kilometers out of town. Poles had worked there previously, but they were paid, whereas we were available as slave laborâunpaid and barely fedâso the Germans brought us in to replace the Poles. We were set to work at enormous machines for twelve-hour

shifts, six hours at a time with a fifteen-minute break between. We worked either 6 A.M. to 6 P.M. or 6 P.M. to 6 A.M. I worked at a machine drilling holes into little metal slugs. I was given measurementsâthe hole had to be so wide and so deepâand it had to be exact. I was required to drill fifteen hundred pieces per shiftâone after the other, hour after hour, day after day. No talking, no sitting. Just drilling holes into metal slugs, precisely so wide, precisely so deep, and placing each one as I finished it into compartmentalized wooden boxes at my side. If I worked, I could live. I was grateful for that. But I knew I could not make a mistake. Mistakes would not be tolerated.

shifts, six hours at a time with a fifteen-minute break between. We worked either 6 A.M. to 6 P.M. or 6 P.M. to 6 A.M. I worked at a machine drilling holes into little metal slugs. I was given measurementsâthe hole had to be so wide and so deepâand it had to be exact. I was required to drill fifteen hundred pieces per shiftâone after the other, hour after hour, day after day. No talking, no sitting. Just drilling holes into metal slugs, precisely so wide, precisely so deep, and placing each one as I finished it into compartmentalized wooden boxes at my side. If I worked, I could live. I was grateful for that. But I knew I could not make a mistake. Mistakes would not be tolerated.

This I learned within days of arriving at the factory. There was a young man, Weinberg was his name. He was a friend of my brother'sâprobably eighteen or so at the time. One day, I saw Weinberg running fast across the grounds, toward the gates of the compound. I wondered why he was sprinting; he, of course, had nowhere to go. Then I saw the soldiers running, too, carrying their rifles, raising them to shoot. And then they didâshoot him, I mean. They raised their rifles and shot this young man dead. Just like that. He crumpled into the dirt, the force of the bullets first propelling him forward, as if pushing him onward for a moment in his desperate stride, but then, and really all at once, because it could have taken only a second or two, Weinberg collapsed on the ground.

Feter! You told me that working would protect me, that if I work I will live. I am here in this factory, I am here drilling these holes. The dreadful noise of these monstrous machines, the metal dust in the air, the monotony of the endless hours, the loneliness, the fear. My legs ache from standing so long.

All so I can live. But what about Weinberg? Weinberg has been working, too, yet he has been killed.

All so I can live. But what about Weinberg? Weinberg has been working, too, yet he has been killed.

Weinberg, it seemed, had made some kind of mistake; that's what the Germans said. They said he was trying to sabotage the ammunition. When the Germans accused him of this crime, he knew what it meant and so he ran. Then he was shot. Then he fell. Then the Germans dragged his body away.

Other books

See No Evil by Allison Brennan

Dreams Take Flight by Dalton, Jim

Castle of the Wolf by Margaret Moore - Castle of the Wolf

Blue Haven (Sunshine & Shadow Book 1) by Williamson, Alie

The Quarterback's Love Child (A Secret Baby Sports Romance Book 1) by Stephanie Brother

Daring Devotion by Elaine Overton

Cut Dead by Mark Sennen

Star Soldiers by Andre Norton

Rebel Kato (Shifters of the Primus Book 1) by Elyssa Ebbott

The Bathrobe Knight: Volume 3 by Charles Dean