Two Rings (4 page)

Authors: Millie Werber

This storyâand the many others like itâdrew me to Jack. He seemed truly heroic to me, a real hero of a man, and not only

because of the obviousâin 1944, he had helped save seven hundred boys who had come to Buchenwald destined for deathâbut because of this determination to be a

mensch

in the world, no matter what the context, no matter what the result. I was proud to know him; I was proud, truly, to be associated with him among all the Radomers in our group. And I found myself wanting to make him happy, to try somehow to make up for all the miseries he had been made to suffer.

because of the obviousâin 1944, he had helped save seven hundred boys who had come to Buchenwald destined for deathâbut because of this determination to be a

mensch

in the world, no matter what the context, no matter what the result. I was proud to know him; I was proud, truly, to be associated with him among all the Radomers in our group. And I found myself wanting to make him happy, to try somehow to make up for all the miseries he had been made to suffer.

But I wanted nothing moreânothing more than the stories and the quiet time in conversation. So when we were sitting together one day, and Jack took that ring from his pocket, rolling it around between his fingers, I didn't respond when he asked me whom it might fit. I knew what he meant. But I couldn't answer his question. Maybe I just smiled a little and bent my head away.

You see, liberation for me didn't feel like a new beginning. You watch these old-time newsreels now of towns across Europe being liberated by the Allied troops, and everyone is out on the streets looking happy and relieved, and women are throwing themselves at the soldiers and hugging and kissing them. As if liberation were the end of it all. As if liberation meant a fresh start. As if it meant real, uncluttered freedom. But that's not how it wasânot for me. I had been “liberated,” yes. But into what? Liberated into an abyss, an oblivion, into a life without moorings.

My brother, Majer, had been shot to death by German soldiers during the liquidation of the Radom ghetto in the summer of 1942. Mima had watched it happen. She told me, too, that my mother and grandparents had been taken away at the same timeâto Treblinka, as we later learned. My father and

uncle had escaped the deportations because they, like my aunt and me, had managed to find work, but Mima and I hadn't seen the men since our arrival at Auschwitz. And Heniek, my husband, was dead. That I knew. That I could feel as a certainty in my blood.

uncle had escaped the deportations because they, like my aunt and me, had managed to find work, but Mima and I hadn't seen the men since our arrival at Auschwitz. And Heniek, my husband, was dead. That I knew. That I could feel as a certainty in my blood.

Â

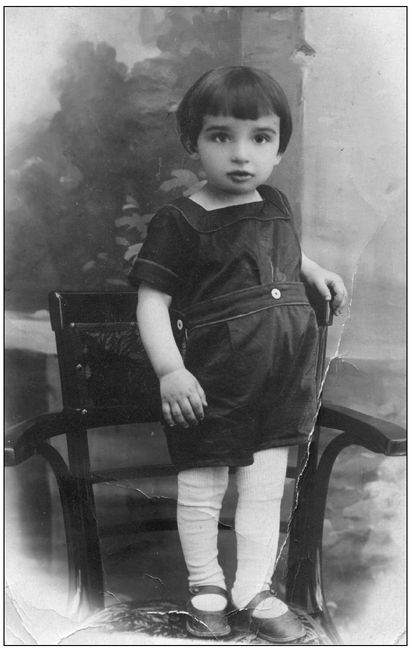

My brother, Majer Drezner, circa 1927

At the moment of my liberation, two thoughts came upon me, very clear and very precise. The first was laced with bitterness, and I spit it out like some bad taste that had lingered in my mouth for years: “I don't want to be Jewish anymore; it's a death sentence to be Jewish.” The other thought rose in me more forcibly from my gut, like a tight knot at the bottom of my belly, a query rather than a claim: “To whom do I belong, and who belongs to me?”

That question had sounded in my head every day since my liberation. I enjoyed being with Jack; I felt comfortable with him. But I refused to let myself fall in love, and I knew I would never marry again. There had already been too much love in my life, and too much loss. I couldn't risk another loss. And I wouldn't betray my first love. To be true, I couldn't fall in love with Jack because I was still so deeply in love with Heniek.

I must explain this love, I know. I was barely more than a child, just fifteen when I first fell in love. The world was falling to pieces, and I was lost and frightened and on my own. I loved a man twelve years my senior, and at sixteen I married him with joy in my heart. In some way, and secretly, I have loved him ever since.

To tell this story, I have to go back, closer to the beginning.

I have to go back to the ghetto.

2

MY MOTHER WAS ALWAYS WORKING. THIS IS MY CLEAREST memory of herâMama at the sewing table, cutting fabric freehand, without patterns, sewing pieces together, making miracles out of bits of cloth. I am a young girl watching her, and I am amazed by the magic of itâthat she somehow knows where to cut, where to stitch, as if the material has some kind of inner logic that she is able to follow without the bother of paper patterns. The swoosh of the dark material as it glides and comes to rest on the table where she works; the dust of the marking chalk floating in the air; the girls who work for her gathered together in focused concentration. It is a mystery to me and a wonder, how Mama can turn these flat and lifeless waves of cloth into the clothes her customers so desire. And how beautiful the clothing is! The dresses and blouses and skirts, all understated but somehow elegant, too. The ladies from the town arrive, Jews, of course, but Gentiles, as well, wearing their fur-trimmed coats and carrying leather handbags. They love my mother's clothes. I know they give her money for her work, but sometimes I see they give her bread instead. One time, maybe this is early in 1941âI am not yet fourteen years old, we have just moved to the ghetto, and there are still a few Polish customers who come to see my motherâa woman arrives carrying a thick book in her gloved hand. I know this woman; she has been coming for years. She is a bit formal perhaps, but kind as well, friendly even to me, as I watch the goings-on from the back of the room, trying not to get in the way. The woman lays her book down on the table to remove her gloves and set down her purse. I look over to see the title:

Mein Kampf

.

Mein Kampf

.

Â

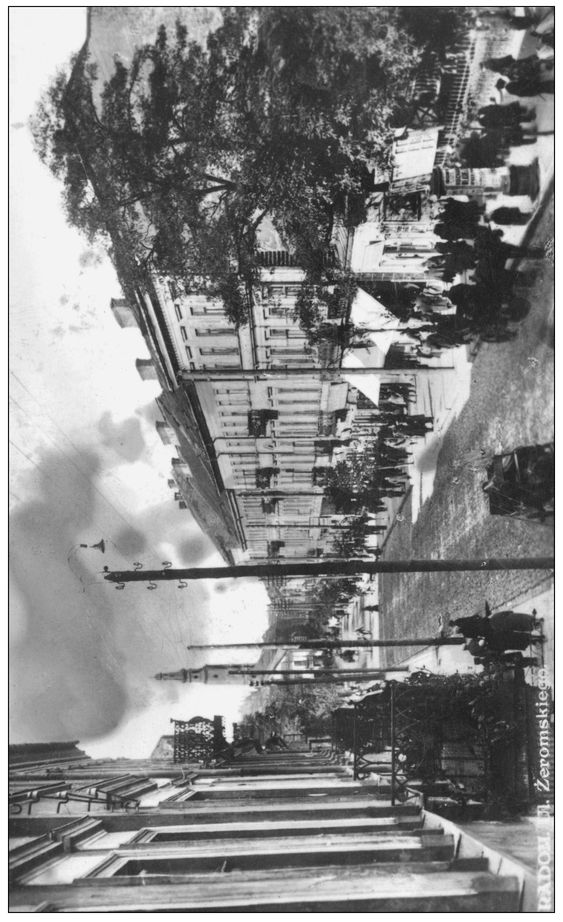

Radom postcard, 1930s

Mama and I shared a bed. Before we moved to the ghetto, we lived in a large, two-room apartment in the center of Radom near City Hall, on Wolnosc Street. The second of the two rooms was separated across the middle by two large wooden wardrobe cabinets in which Mama kept her sewing materials. In the back section of the room were two beds, one for my father and brother and one for Mama and me. My father lived in Paris for the first seven years of my lifeâI think he felt it would be easier to make a living there than in Polandâbut even when he came home in 1935, he slept with my brother, and Mama with me. I loved being in bed with Mama, nestling in her warmth at night under the feather blanket.

In Europe in those days, it wasn't the way it is now in America, where parents endlessly praise their children and

hug and kiss them every day. Mama didn't hug me much, and I don't remember her ever telling me that she loved me. “Why do I have to tell my daughter I love her?” she would have wondered. “Of course I love her; I'm her mother!” I didn't miss it, though, because I didn't know anything else. Besides, in bed, I didn't need Mama's words; I felt her love every night in her bone-weary embrace. Sometimes I would massage her feet before she fell off to sleep, her muscles slowly releasing, softly relaxing in my hands. Then I would crawl under the feather blanket with her and feel her warm breath on my back.

hug and kiss them every day. Mama didn't hug me much, and I don't remember her ever telling me that she loved me. “Why do I have to tell my daughter I love her?” she would have wondered. “Of course I love her; I'm her mother!” I didn't miss it, though, because I didn't know anything else. Besides, in bed, I didn't need Mama's words; I felt her love every night in her bone-weary embrace. Sometimes I would massage her feet before she fell off to sleep, her muscles slowly releasing, softly relaxing in my hands. Then I would crawl under the feather blanket with her and feel her warm breath on my back.

Â

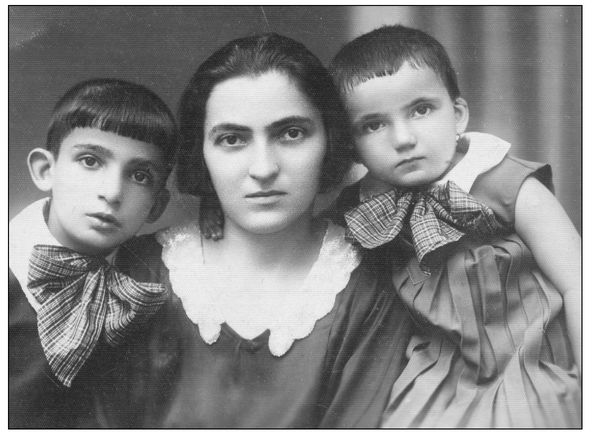

Majer, Mama, and me

The front part of the large room served as both living room and salon for Mama's customers. She laid out ladies' magazines

on a little coffee table she set there, and her clients would flip through the pages and choose the items they wanted her to make.

on a little coffee table she set there, and her clients would flip through the pages and choose the items they wanted her to make.

The kitchen was the workroom, with a large table in the center, where my mother stood for hours cutting and sewing her fabrics. She taught me to cut the fabric exactly right, because material was expensive and her clients always wanted to buy just a bit less than they really needed. If Mama told them they needed three yards to make a dress, they'd buy two and a half yards instead to save a little money. So there was no room for error; every cut had to count.

At the height of her business before the war began, Mama had four women sewing for her. They worked long hours, but she treated them well and helped them save up to buy sewing machines for themselves. That was a big deal, a sewing machine. It was transportable, first of all, so no matter where you had to go, no matter what the situation, you could take the machine with you and earn a living. When the ghetto was established in 1941 and we had to leave our apartment on Wolnosc Street and move in with Mima and my uncle and their two children, Mama brought along her sewing machine. She had hoped that she could continue to work, even in the ghetto. But there was no room to sewâeight of us at that point were living in a single roomâand after the first month or two in the ghetto, there were no customers. One of the girls who worked for Mama managed to leave Poland before the war began. She went to Paris, and she brought her machine with her so she could work, so she could live.

Â

Mama is second from the right; Mima is sitting beside her

Mama wanted me to learn to sew so that I would have a trade. Sewing and embroidery were the two professions acceptable for girls. Mama was successful in her businessâshe kept us housed and fedâbut it seemed to me that she worked all the time, until we lit candles on Friday night and then again as soon as Shabbos was over. When my father lived away, it was Mama who supported me and my brother. My father did send home some money, I think, and I know he sent occasional treatsâcanned sliced pineapple, for example, which I happily devoured between pieces of buttered cornbreadâbut it was my mother's sewing business that kept our household together. I was youngâbarely a teenagerâand Mama wanted to teach me, too. Perhaps she had a sense that a woman needed to learn to provide for herself, in case she had no one else to rely on.

Other books

Maybe This Time by Joan Kilby

Fabulous Five 030 - Sibling Rivalry by Betsy Haynes

Awake by Egan Yip

Getting In: A Novel by Karen Stabiner

Napier's Bones by Derryl Murphy

Dead at Breakfast by Beth Gutcheon

Elizabeth's Wolf by Leigh, Lora

How We Decide by Jonah Lehrer

Seaborne by Irons, Katherine