Two Rings (24 page)

Authors: Millie Werber

The last time I had been on such a march, eight months earlier, we had walked from Radom to Tomaszów, in the scorching heat of high summer. Now, in late March, the weather was still wintry, especially at night, and the road was stiff with frozen mud and ice. We walked pressed against each other to shield ourselves from the cold. We were a long and weary column, perhaps two hundred of us in all, flanked on either side by our still-anxious German guards, clutching the guns slung across their chests, their heavy boots crunching in the ice. We walked for two nights in the wicked winter cold, not knowing where we were being led or what the Germans would do with us. During the days, we were hidden from sightâonce, I remember, in an abandoned barn filled with hay. I thought the Germans were locking us in to set fire to the place; I thought we were about to be burned alive. I waited a long time in that barn, straining to hear the first crack of flame.

Then, on the third morning of the march, it ended. Literally out of nowhere, out of an otherwise empty sky. It was very early, just before dawn, and the air had that feeling of freshness that can sometimes emerge in the moments when night seems ready to give over into day. I was chilled, and I clutched my coat at the collar to try to keep off the dampness of the air. Mima was walking beside me, our arms nearly touching for the warmth. We were very tired, exhausted really, after another long, dark night of walkingâafter so many years of war. I could tell we weren't far from a townâKaunitz, as it turned outâbecause the road had gotten firmer under our feet and I thought I could see lights quivering in the distance. People were getting up with the dawn, readying themselves for another day.

Then we heard the rumble of airplanes, a muffled roar approaching in the brightening light of a gunmetal sky.

As if in response to some silent command, the guards started to shout at us all at once: “Get down! Everyone, on your bellies. Faces down!” A sudden eruption of activity broke the monotony of our endless walk. The soldiers, unslinging their guns, ran to surround us as we fell to the ground. Someone yelled out the order again: “No moving! Don't lift your heads!” I dug my face into the frozen dirt, certain the Germans would shoot. I could feel Mima next to me, but I was too scared to inch my way over to find her hand. I did as I was told: I lay still; I didn't move my head. Above us now, the boom of airplanes roaring by; around us, the anxious breath of the soldiers stamping their feet in the cold. Did it last an hour? Maybe just ten minutes. I don't know.

Then shooting began. Not at us, but not too far awayâdown the road some small distanceâwe heard the rapid crack of gunfire. “We're next. We're next,” I kept thinking. “Now is when I'm going to die.” I had decided that it would be worse than a bomb blast, that it would take longer to die from a gunshot. I didn't want to die slowly; I didn't want to die in pain. I breathed in the dirt, bits of grit flecking my frozen lips. I kept my eyes tightly shut. I tried to ready myself for the bullets.

Â

Â

Â

Sometime later, we heard that it was another group of women who had left the factory with usâa group of Russian prisonersâthat had been shot. They had been walking ahead of us, and they, too, had been ordered to get down as the sound of the planes approached, and then the Germans shot them, every one of them, right on the road. Apparently, this little

massacre led to our liberationâbecause just as the Russians were being shot, the Americans were flying overhead, and when they saw what was happening belowâwomen being shot in the backâthey decided to intervene. So down they came in parachutesâdozens of them, falling from the sky. We had the impression that they didn't have prior orders for this, that it wasn't planned, because when Mima said it was safe to look up, to lift my head from the dirt (a thing I didn't want to do; I didn't believeâI couldn't believeâthat the Germans had fled), I saw soldiers, American soldiers, falling randomly from the sky, and some of them were bloodied from their fall, some had landed on the fences by the side of the road, their parachutes caught in the wooden posts. One young soldier I saw was dangling from the limbs of a tree. But Mima was rightâit was safe to lift our heads, because the Germans had run away. We arose, dazed and disbelieving, and found ourselves surrounded only by Americans, young men talking in a language we didn't understand but telling us news we did. It was over: The Germans were gone; we were free.

massacre led to our liberationâbecause just as the Russians were being shot, the Americans were flying overhead, and when they saw what was happening belowâwomen being shot in the backâthey decided to intervene. So down they came in parachutesâdozens of them, falling from the sky. We had the impression that they didn't have prior orders for this, that it wasn't planned, because when Mima said it was safe to look up, to lift my head from the dirt (a thing I didn't want to do; I didn't believeâI couldn't believeâthat the Germans had fled), I saw soldiers, American soldiers, falling randomly from the sky, and some of them were bloodied from their fall, some had landed on the fences by the side of the road, their parachutes caught in the wooden posts. One young soldier I saw was dangling from the limbs of a tree. But Mima was rightâit was safe to lift our heads, because the Germans had run away. We arose, dazed and disbelieving, and found ourselves surrounded only by Americans, young men talking in a language we didn't understand but telling us news we did. It was over: The Germans were gone; we were free.

They had been standing above us just moments before, their guns pointed at our backs, readying themselves to shoot. But then, instead of shooting, they ran. It was only a minute, a second, that separated my life from my death. I could have been dead; I was about to be dead. But, insteadâI don't know whyâI was alive.

The edge between life and death is so sharp, so arbitrary, so senseless.

Â

Â

Â

Liberation was a bewilderment to me. I remember throwing aside the little packet of sugar I still had with me from

Auschwitz, thinking suddenly that I wouldn't need it anymore. I remember thinkingâno, I remember knowing, with clarityâthat I no longer wanted to be a Jew, that I wanted simply to be a human being without the encumbrances of history and obligation. And I remember a sudden fright, a terrifying question rising up in me from the hollow of my gut: To whom do I belong, and who belongs to me?

Auschwitz, thinking suddenly that I wouldn't need it anymore. I remember thinkingâno, I remember knowing, with clarityâthat I no longer wanted to be a Jew, that I wanted simply to be a human being without the encumbrances of history and obligation. And I remember a sudden fright, a terrifying question rising up in me from the hollow of my gut: To whom do I belong, and who belongs to me?

I had Mima: I know that; I knew it then. Still, I had lost what mattered most: my mother, my Heniek. Standing amid exuberance, amid tears of thankfulness and disbelieving smiles, I was shaken by a wrenching awareness: I was free, I would have a future, but I would enter it alone.

14

IN THE SEVERAL MONTHS BEFORE JACK DIEDâIN 2006, AT the age of ninety-twoâhis thoughts often returned to our time together in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Jack loved me very muchâI say this with simple candorâand I know it gave him pleasure to see me well dressed and well fed, to see me surrounded by beautiful things. We started together from nothing; once our real estate business became successful, he wanted to see that I should always have everything. He called me his queen. From the start and even into our old age, he said that the world was envious that he walked with me on his arm. But in the endâat the endâwhat mattered most to him was that I had come to his doorstep in 1945.

“I cannot believe that you came to me, that you came looking for me. I am not a believer, Millie, but I believe God sent you to find me.”

He was thinking of Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Â

Â

Â

Jack, too, had been alone in the world. Except for his brother Mannes, who had moved to New York before World War I and whom Jack had never met, all of Jack's siblingsâthere had been eight children in allâwere gone. Some had died before the war; some were killed during it. Most of his cousins were killed as well, as were nearly all of his nieces and nephews, and his father and grandparents, tooâhis mother had died when he was a young child. His wife, Rachel, to whom he had been married for just three or four years when he was arrested, and his little daughter, Emma, were both gone. A flourishing, thriving family, all now dead. At the edge of despair, Jack had managed to find purpose and a will to live in his efforts to help save nearly seven hundred boys who had come in a transport to Buchenwald in the summer of 1944. After the war, Jack eventually found his way to Garmisch-Partenkirchen, and he moved in with one of his cousins who had survivedâItamar, who was living in that apartment he shared with the group of other Radomers.

Jack had been in Garmisch for several weeks when I arrived late in the summer of 1945. Like an angel out of the wilderness, a harbinger of happiness, I came. That is how Jack saw itâor, that is how he wanted to remember it, that in all the world, I managed to come searching for him, to raise up his soul from the devastation of the war. In the final weeks of his life, that memory rose up again and lingered with him. In those last weeks, he mentioned it often.

It wasn't true, exactly, that I had come to Garmisch-Partenkirchen looking for Jack. Mima and I had come because

we were looking for Radomers, and when Mima wanted to move on, when she wanted to go to Italy because she had heard that her husband and her brother-in-lawâmy fatherâwere in Bari waiting for a boat to Palestine, she left me with Jack or, at least, in Jack's protection. She said simply: “You'll be safe with Jack.”

we were looking for Radomers, and when Mima wanted to move on, when she wanted to go to Italy because she had heard that her husband and her brother-in-lawâmy fatherâwere in Bari waiting for a boat to Palestine, she left me with Jack or, at least, in Jack's protection. She said simply: “You'll be safe with Jack.”

I did feel safe with Jack. I was riveted by his stories, by the enormity of his hardships, by his determination to get through it all. He was so smart and so strategic in his dealings with his captorsâfiguring out exactly which rocks were best to pick up, or working out where exactly to hide the many children in his charge so the Germans wouldn't find them. I admired him for this, and I pitied him, too, for the horrors he had enduredâhanging for hours by his upturned arms from a gallows, being whipped on his naked back until he fainted from the pain, being buried once under corpses and rescued only by happenstance. Compared with his, my own stories to me seemed insignificant. Maybe, knowing that he could go on and envision a future for himself despite his past helped me to see that perhaps I could, too.

Jack had lost his wife and child, as I had lost my Heniek. We spoke about this, at least a little. I could never bring myself to tell Jack everything about my feelings for Heniekâand why should I, really? He didn't need to know all the details, just as I didn't need to know every detail about his wife. But talking to each other about even the outlines of our previous loves brought us closer together. Honesty does that.

Still, though, I was certain I wouldn't marry again, and I told Jack so. That, too, surprisingly perhaps, brought us closer to each other, perhaps because it made Jack pursue me with

more persistence, but also I think because knowing I wouldn't marry him, and so knowing that nothing really was at stake, allowed me to feel comfortable with him. It made me feel safe, for the first time in years.

more persistence, but also I think because knowing I wouldn't marry him, and so knowing that nothing really was at stake, allowed me to feel comfortable with him. It made me feel safe, for the first time in years.

My determination not to remarry slowly faded, imperceptibly almost, over the several months I spent in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. I found myself seeking out Jack's company. So after many hours of quiet conversation, when he sat, twirling that ring between his fingers, asking, “Whose finger will this fit?” I found myself suspecting that it would fit mine.

We decided to go together to Italy.

Â

Â

Â

By this time, Mima had been away for weeks and we hadn't heard anything back from her or from anyone who had seen her. I wanted to find out what happened and whether she had found Feter and my father. This is how it was after the warâJews traipsing all over Europe, jumping on trains, sleeping in abandoned buildings, trying to find anyone in their family who might still be alive. As it turned out, Feter and my father had been told that Mima and I had been killed in Auschwitz; a woman they knew from Radom had told them that she had seen us going to the gas chambers. So they had gone to Bari, where they heard you could get smuggled to Palestine. Mima wound up finding them there, in Bari, but the meeting brought relief and devastation at once. Mima learned then that although Feter had survived, their son, Moishele, had not. She had seen Moishele last when the men were taken away at Auschwitz, and all the time since then she had been hoping, praying, that Feter might have been able to protect him, to save him from the gas chambers.

Â

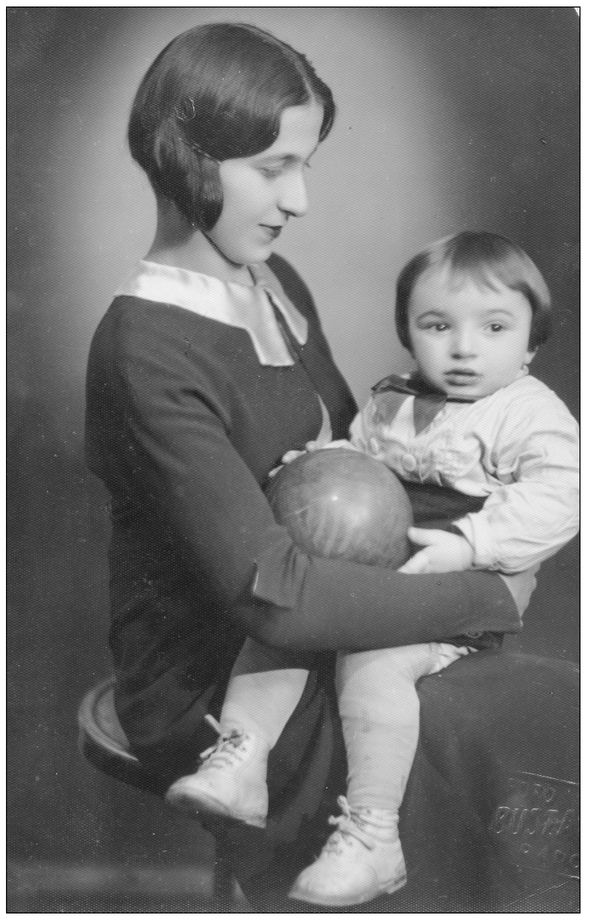

Mima and Moishele before the war

I don't think Mima ever recovered from what she learned that day in Italy. None of us recovered, really, from the warâit's an absurdity, a way of not wanting to deal with things, to pretend otherwise. But Mima had held her hope for Moishele so close to her heartâI think maybe all the time she was protecting me, there was some part of her hoping that Feter was doing the same for their son. But Feter hadn't been able to protect him.

Other books

Pretty In Pink by Sommer Marsden

Nightingale Wood by Stella Gibbons

The Lives of Others by Neel Mukherjee

Adrenaline by Bill Eidson

A Time For Hanging by Bill Crider

The Noble Pirates by Rima Jean

Royal Pain: An Alpha Bad Boy Billionaire Romance by White,Jane S.

Shadows: Book One of the Eligia Shala by Gaynor Deal

The Life of Polycrates and Other Stories for Antiquated Children by Connell, Brendan

La abominable bestia gris by George H. White