Two Rings (21 page)

Authors: Millie Werber

We are taken to be shaved. We stand in line before a row of women, Jewish inmates they are, standing across from us with straight razors in their hands. Each in turn, we stand before them, and each one of us gets shaved. Everywhere. Our heads, under our arms, between our legs.

“Arms up! Spread your legs!”

Razors scraping against skin. Razors scratching, nicking the flesh. Little pellets of blood rise up on my stinging skin. I ask, timidly, tentatively, “Please, will you save some hair on my head?” I have always had such fine hairâbaby hair, I call it. Silly, I suppose, to be concerned about so small a thing. Sillier still to think that my simple request might ever be granted. The woman grabs my hair in her fist, pulls hard, yanking up the skin of my scalp, and swipes her razor across my head. She cuts off my hair; she slices off a small piece of my scalp.

In the Auschwitz museumâI visited there in 1987âthere are rooms filled with the things the Germans confiscated from the Jews: thousands of suitcases, a storeroom of eyeglasses, shoes of every size, a mountain of human hair. All that hair, shaved from all those heads. And attached at the ends of those fragile strands, for a time, at any rate, little bits of scalp, shards of Jewish skin.

Eventually my hair grew back, except for in that one place where my skin was shorn. The skin grew back, but never the hair.

Next, the Entlaussung, the delousing.

Again, we stand before Jewish inmatesâhard, harsh women, willing to do such atrocious things.

Again, “Arms up! Legs open!”

They dunk dirty rags into buckets of some liquidâa disinfectant, a delousing agent. The woman before me lifts her rag dripping with the stuff. I am no one to herâa naked body without a history, without a name. I am no different from the hundredsâsurely the thousandsâwho have stood before her. Today, yesterday, last week, last year. This woman works blindly at her station as I worked at mine at the factory. I am a nothingness before her. She slaps the rags up and down my naked body. Liquid fire, acid eating away at my bleeding skin. My head, my underarms. Between my legsâso private, those parts, so delicate, throbbing now, scorching. I am aflame. My body on fire.

Â

Â

Â

This is Auschwitz, this indignity, this torture. Everyone knows this now; everyone knows now about the nightmare of Auschwitz, about the walking skeletons, about the crematoria, about the Final Solution. Nowadays you see a picture of naked, shaven women standing dazed in a barren yard somewhere in Auschwitz, and the image is horrifying, of course, but by now it is familiar, too. Everyone has seen these pictures; our children have been raised on them. But then, we didn't know about any of this. These insults to our bodies, to ourselvesâto our sense of our selvesâthey shocked us just as much as they were degrading and filled with pain. That first day in Auschwitz was filled with things that seemed insane: Someone put a pocket watch in her vagina! Who does this? In what kind of world is someone made to do this? We had lived through the war already for five years. We had been through much; all of us had been through much.

But until now, we had lived in a world that we recognizedâa frightening world, a cruel world, to be sure, but it was a world we could understand, too. The reality of Auschwitz was unrecognizable. These affronts stunned us, tore us brutally from anything we were able to decipher for ourselves, and dropped us into the panicked insanity of this horrible, horrifying place.

But until now, we had lived in a world that we recognizedâa frightening world, a cruel world, to be sure, but it was a world we could understand, too. The reality of Auschwitz was unrecognizable. These affronts stunned us, tore us brutally from anything we were able to decipher for ourselves, and dropped us into the panicked insanity of this horrible, horrifying place.

Â

Â

Â

And then the showers. How can I describe this? Hundreds of us, petrified and disoriented, driven into a cement-walled chamber.

There are round spigots hanging from the ceiling. This is a gas chamber; I am sure of it. We have been herded into this room to be gassed. I am going to be gassed.

My heart is pounding, my breath is fast and shallow. My mouth is so parched my tongue sticks to my teeth. I wait moment by moment for the end, for the gas, to breathe poison. I look up at the spigots, watching for the gas. Will it burn my insides, that first breath? Will it take long for me to die? This waiting is the worst, the anticipation of the physical torture to come.

Women are screaming, wailing. Hundreds of women huddled together on the verge of a massive murder. I cling to Mima, her arms wrapped around me. We will be together when we die. But I want Mama. More than ever, I want to be with my mother. It is horribleâI can't say it another wayâit is horrible to be in this room waiting for the gas.

The spigots open, and out of themâwater. Scalding hot, then freezing cold, then hot and cold again. But water, not gas. Water.

We emerge from that chamber transformed. Truly, we can barely recognize each other; without hair, we all look like men. We gaze into each other's eyes to see if we can see ourselves in someone else's pupils. We want to know what we look likeâshorn and swollen, devastated, but grateful, too, for we haven't been killed.

Each of us is given a dress. You get whatever is handed to you. Tall women get short dresses, short women get long ones. No bra, no panties. Just a dress. For shoes I got a pair of wooden clogs that had never been sanded or smoothed out on the insides. It was an unequaled agony, walking barefoot in these clogs. I have nightmares about them even now.

I lost my period at Auschwitz, and I said it was a blessing. What would I have done with a period? How would I have managed that?

11

I REMAINED IN AUSCHWITZ FOR ALMOST SIX MONTHS, FROM July 1944 until just before the end of the year. Auschwitz was a daily dread: The threat of death, of being “selected,” was with us every day. We saw the smoke of the crematoria; we knew what was possible. Twice a day, we stood for the appels; every so often, we were made to stand naked, and an SS officer would come to look us over and select women from the line. I always stood with my head bent down, trying to cover myself with my eyes.

Â

Â

Â

Auschwitz is now called an extermination camp, a death factory. Ten thousand people were killed in a single day in Auschwitzâmore than one million people in all. It looked like death thereâskeletal bodies, sunken eyes, black smoke from the chimneys. And the stench, the stench of what was burning. Nothing grew at Auschwitz. The place was more barren than a desert, as if nature itself knew that Auschwitz

was the kingdom of death. Not a tree or a shrub, not a blade of grass. Not a fly. Nothing. Auschwitz was the end of the world, death's domain.

was the kingdom of death. Not a tree or a shrub, not a blade of grass. Not a fly. Nothing. Auschwitz was the end of the world, death's domain.

I had no sense then of the overall operation of the place, no awareness of its intricate structures, its hierarchies of power and systems of barbarity and barter. I knew only my own experience; I had only my own partial, incomplete view. People needed to survive; no one had the means to survive. Violence was the norm. My months at Auschwitz were focused on only what mattered mostâfood, shoes, staying unnoticed. I had my aunt, and I had a good deal of luck. I cannot describe what Auschwitz was “like,” for it was like nothing else that ever was; I can offer only pieces, those that live in me still.

I was hungry all the time. Every morning, we got tepid brown liquid and a slice of hard bread. After the evening appel, we were given thin broth. Every day, the same; every day, not enough to calm the pain gnawing at my gut. My hunger was like an animal I carried inside, an animal that periodically unfurled its claws and scraped at the edges of my belly. It might lie quiet for a time, perhaps when I was talking with Mima or focused on some small labor. But not often, and never for long. That scraping, that digging, that pain inside my gutâit never went away. It was there when I went to sleep at night, and it greeted me as soon as I awoke in the morning. In Auschwitz, bread was precious beyond measure, precious nearly beyond love.

But maybe not quite. Or not for everyone.

Not, at least, for Mima.

Â

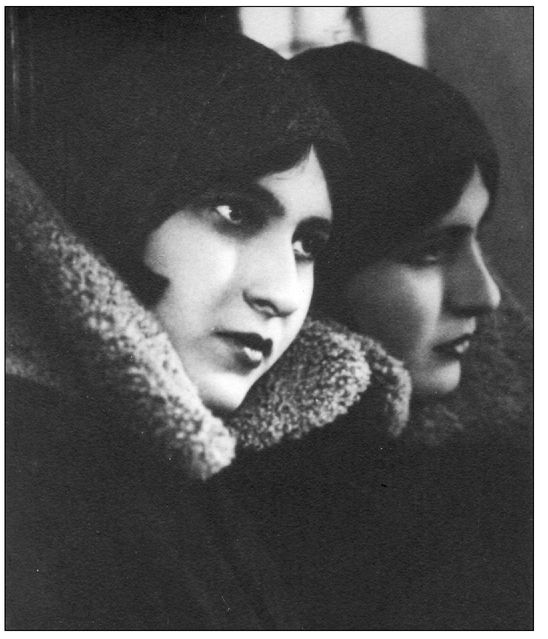

Mima, 1932

Everyone needed a partner in Auschwitz, someone to watch out for you, someone to hold your bowl and spoon when you went to the latrine. Mima was my partner. I don't know during those days and months at Auschwitz if I provided any solace for my aunt, if my life and her daily determination to protect it gave her any strength, any inner resolve to hold on.

I hope they did; I really do hope her care for me was good for her, because I know with perfect clarity how good it was for me. I know what would have happened to me in Auschwitz without her.

I hope they did; I really do hope her care for me was good for her, because I know with perfect clarity how good it was for me. I know what would have happened to me in Auschwitz without her.

Â

Â

Â

After we got our slice of bread in the mornings, my habit was to take just two bites and then leave the rest for the duration of the day and into the next morning. I wanted to take the last nibble of bread just before we got our next day's portion. I was frightened to be without food, even if it was only a single bite of bread. The others used to scold me: “You'll never feel full this way. You must eat your full portion so you won't starve.” But I never knew what the next day would bringâwould there be food tomorrow? Would we get another piece of bread? So I preferred to have my bread this wayâtwo small bites in the morning, a bite or two during the day, a piece left over for when I woke up.

I needed to keep the bread overnight. I couldn't simply hold it, because it might fall out of my hand while I slept and then surely someone would pick it up and eat it herself. My dress, of course, had no pockets. So Mima let me use her shoe. Mima and I shared the same bunk, and at night, we used her shoes as pillows. We had to sleep on them because they, too, would have been stolenâeverything in Auschwitz you didn't hold on to was immediately stolen. So at night, Mima and I slept on her shoes, each of us with one hand on the shoe under our own cheek, and the other hand holding the shoe under the cheek of the other; this way, we would be sure to know if someone tried to take either shoe while we

slept. Nestled together in this way at night, we protected our possessions: One shoe under Mima's head held her ring in its heel; the other, under mine, held two pictures under its lining and a crust of bread at its toe.

slept. Nestled together in this way at night, we protected our possessions: One shoe under Mima's head held her ring in its heel; the other, under mine, held two pictures under its lining and a crust of bread at its toe.

Other books

Married to the Viscount by Sabrina Jeffries

The Village by Alice Taylor

Ties That Bind by Debbie White

Hallow House - Part Two by Jane Toombs

ShameLess by Ballew, Mel

Prey by Linda Howard

No More Vietnams by Richard Nixon

Shifu, You'll Do Anything For a Laugh by Yan,Mo, Goldblatt,Howard

Born to Endless Night by Cassandra Clare, Sarah Rees Brennan