Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (15 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

‘We are surely the first ever to clap eyes upon these forms of life!’ Lebret declared. ‘There are dozens of Nobel prizes in science to be claimed if we could capture one!’

‘They look like,’ said Boucher, in an awed tone, ‘like men!’

‘Are they

mermen

?’ asked Avocat. ‘Have we passed from reality into a realm of legend and myth?’

‘Hardly that,’ observed Lebret. ‘It is surely nothing more than a freak of parallel evolution. Their flippers or … tentacles, or whatever they are, merely

resemble

limbs.’

‘They are certainly unlike any kind of cuttlefish hitherto observed,’ was Ghatwala’s opinion.

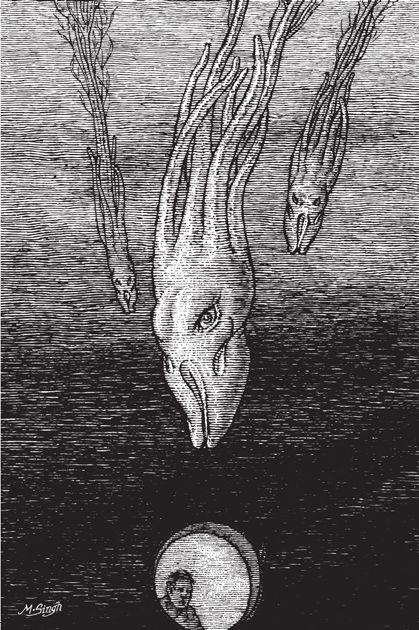

The creatures possessed skinny torsos, from which two front and two rear fins (or perhaps they were fat tentacles) trailed; and their bullet-shaped heads protruded necklessly from their bodies. They

were of a silvery-blue or blue-white colour, as fish tend to be; their eyes were black saucers and their mouths gaped on under-jaws shaped like a Norman arch. Yet despite all these obviously piscine qualities, there

was

something uncannily human-looking about them – something to do with their undulating passage through the water, some freakish reminiscence of mankind about their arrangement of body, head and limbs.

Yet the most distinctive thing about them had no human analogue. From their ‘shoulders’ sprouted two great seaweed-like appendages – five or six times as long as their actual bodies, branching and bifurcating into a foliage-like complexity away from their bodies. As the creatures swam and circled about the observation porthole these great doubled bunches folded, and swirled, following after like two great crinkled capes.

‘Gills?’ suggested Jhutti.

Lebret seemed to have recovered his spirits. He was right up against the glass. ‘Marvellous!’ he breathed. ‘Exceptional! The cape-things

must

be gills. There was no oxygen in the higher, black water – but down here, with a source of light and heat and blue-green algae, there must be some.’

‘External

gills, though?’ said Ghatwala. ‘And of such prodigious size?’

‘It suggests that such oxygen is here is in low concentration.’

‘They’re certainly fascinated by

us

!’ Lebret noted. ‘And why not? They’ve surely never seen anything like it in their lives.’

‘Visited by the great metal whale!’ laughed Boucher.

‘Perhaps they will worship us as a god, as the South Sea Islanders did Captain Cook?’ Billiard-Fanon suggested.

‘Did the South Sea Islanders not murder Cook?’ said Ghatwala.

‘That was afterwards. And anyway,’ said Boucher. ‘They are but fish. They clearly do not possess the intelligence to …’

There was a loud

thump

. One of the fishmen had thrust itself up, suddenly, close against the glass of the observation porthole. The collision was not accidental. The creature grasped the slight bulge of glass with two forward flippers – lined with suckers like the holes in Swiss cheese – and battened his large mouth against

it. The overlong lower jaw was clearly capable of being extended and retracted, and its shape adjusted to the contour of glass. A fat, black tongue, covered in rasping protrusions, slithered up from the beast’s throat and licked horribly over the outside of the window.

Lebret had recoiled from the glass at the impact, but he now stepped forward again. The black eyes of the monster swivelled, following him. ‘He’s watching me,’ he observed.

More thumps and bangs were audible, at various points along the metal hull of the vessel. Castor and Capot hurried from the observation room.

‘What are they doing? Is it trying to bite through the glass?’ asked Boucher.

‘I think we should move away, Lieutenant,’ said Jhutti.

The creature affixed to the observation window was still rubbing its black tongue against the surface. Then, abruptly, everything inside dimmed. It took a moment for the people inside to see why – the creature had brought its two huge cloak-gills round and draped them across the glass.

Ghatwala took another photograph, and cursed the light. ‘Where are the flashbulbs stored?’ he asked.

‘Lieutenant,’ said Billiard-Fanon. ‘I concur with the Indian gentleman. I suggest we ascend immediately, and try to shake off these …’

There was a horrible crunching sound; the metal fabric of the

Plongeur

shook and thrummed like a gong.

‘They’re ripping us to pieces!’ yelled Boucher. He leapt up, and made to run up the sloping floor and out of the observation chamber. But he was too hasty; his footing was not sure, and he fell, knocking his forehead against the bottom lip of the hatchway.

‘Lieutenant!’ cried Billiard-Fanon, leaping to the fallen officer. He turned Boucher over – a smile-shaped cut had been grooved into the man’s forehead, and blood was flowing freely from it. He groaned, still alive, but close to insensibility. ‘Avocat! Help me move the lieutenant.’

There was another terrible wrenching, shuddering noise; like metal being cut by giant scissors.

‘What is going on?’

‘They want to eat us!’ cried Ghatwala.

‘What creature eats metal? No – no – I believe it’s our air,’ said Lebret. ‘Our air. They’re greedy for our air!’

The whole of the

Plongeur

shook, leaned through twenty degrees, and tilted further forward. The men inside the observation chamber tumbled and fell, scrambled back to their feet.

Lebret leapt over the supine form of the lieutenant, and scrabbled up the steeply sloping corridor, hauling himself physically into the bridge. ‘Le Petomain,’ he called. ‘Release

air –

open the forward vents and release air.’

‘Where’s the lieutenant?’ the pilot demanded.

‘It’s life-or-death man! Do as I say!’

But Le Petomain hesitated.

Jhutti and Ghatwala were just behind him, pulling themselves up into the bridge. ‘What is on your mind, Monsieur?’

‘You said yourself – oxygen levels down here must be very low. They can smell it in us! They want it! They have somehow intuited that we’re full of it. I don’t know how. But they can never have experienced the stuff in gaseous form. They cannot know how reactive the stuff is. They’re moths to the flame … well,

let the flame burn them

, and shake them off the

Plongeur

. Sailor – do as I say!’

The pilot looked from the scientists to Lebret and back again.

Suddenly the whole craft shuddered violently, and the three standing men fell to their knees. A cacophonous din resounded through the air.

‘Too late—’ shouted Le Petomain. ‘Too late – they’ve pulled the port vent clear off—’

‘I must

see

,’ said Lebret.

He slid on his rear down the sloping corridor, past Billiard-Fanon and Avocat who were endeavouring, with only limited success, to haul the unconscious lieutenant up the shuddering, bucking vessel.

The observation porthole was free again; the sea-beast that had been battened there had gone. Great constellations of bubbles flushed past the glass, not only floating upwards, but disseminating

in every direction. The mermen-creatures were twisting and struggling, their gill-cloaks tangling about them. They contorted in agony – or in ecstasy, it was impossible to tell.

The whole vessel tilted once again, and bubbles flew past the glass. Lebret’s could feel in his stomach that they were sinking.

He could hear the shouting from the bridge as Le Petomain expelled the remaining water from the one remaining functioning ballast tank, attempting to compensate for the loss of air in the other. The whole structure of the

Plongeur

shuddered. The white-noise of the air pumps cut cleanly through the other various noises – the groaning of the metal, the clangs and bangs, the weird subsonic groaning or moaning side.

But the port tank was full of water, and filling the starboard tank with air made the whole vessel pendulum and swing, as if suspended from its front-right. Lebret was thrown against the wall of the observation chamber. Avocat came tumbling back through the hatch, head over heels.

The craft pendulumed round, bringing the observation porthole up. For a moment it hung there, and Lebret got a glimpse of a swarm of mermen. It looked like the feeding frenzy of a school of sharks, jerking and massing around the globular structures of the released air. The bubbles spread and roiled, but – crazily – did not rise through the water. Hundreds of the strange-looking cuttlemen darted at the bubbles, only to flinch sharply away.

Then, still sinking, the

Plongeur

swung back around its own hinge of partial buoyancy and Lebret and Avocat were rattled around the observation chamber. By wedging his feet against the place where one of the room’s seats was bolted to the floor and grasping at the walls with both hands, Lebret was able to prevent himself being thrown through the air. Avocat was not so lucky – he cried out in pain as he was slammed hard against the wall a few yards to the right of Lebret.

The light – bright and blue-white and evidently hot – came into view below them. Then the whole craft swung further about, the light slipped away right, and the swarm of mermen about the released air was visible again. The frenzy was further away

now, a pattern of pulse and flow like sardines being pursued by a swordfish.

‘Brace!’ came Le Petomain’s voice. ‘Brace!’

The

Plongeur

began to swing back, and a sound loud as a cannon report was added to the other clangs and drones. It was the vent to the starboard tank giving way. The vessel vomited out a giant bladderwrack mass of bubbling air, and fell hard away down.

Robbed of all buoyancy, the

Plongeur

was falling now, nose down – directly towards the source of heat and light.

An alarm began to sound. After several ear-splitting seconds, somebody on the bridge shut it off. The whole craft rocked sickeningly, its metal flanks groaning under the torsion like a whale in mournful song.

Lebret made his way across the obstacle course that the observation room had become towards Avocat. ‘Are you alright?’

‘My arm!’ cried the sailor. ‘Broken!’ His face behind his beard was the white of cooked fish flesh.

‘Let me see,’ said Lebret.

‘I

heard

the bone snap,’ Avocat gasped. ‘Like a stick burning in a fire!’

Lebret tried to pull the sailor’s jacket off, as the

Plongeur

swayed and fell, but Avocat’s yelps of pain dissuaded him. ‘Give me a belt to bite upon at least, Monsieur, for pity of the Virgin Mother!’ he cried out. ‘Or fetch me some brandy!’

The shouts of other men could be heard far away in other portions of the submarine. ‘Why didn’t those air bubbles float away?’ Lebret muttered to himself, unsnaking his belt from his trouser loops. ‘What’s the

nature

of this strange place?’

‘We’re going

down

,’ moaned Avocat. ‘I can feel it in my spine and guts – Christ have mercy. We’ll all die! Oh, Christ have mercy!’

‘Le Petomain!’ boomed a voice, from the bridge, echoing through the speaking tube. ‘Straighten her out!’ It was a moment before Lebret recognised it as Castor’s.

‘I’m trying, chief!’ called back the pilot.

Lebret gave Avocat the belt, and the sailor fixed it between his teeth. The ends thrashed and flailed in the air like a snake. Then, as the vessel rocked back on its swing, Lebret wrenched the man’s jacket off him and quickly rolled back the shirtsleeve. The wound was revealed – a bad fracture. A triangle of bone broke the skin like a shark’s-fin poking above the surface of the sea. There was a great deal of bruising, with only a few trickles of blood. Under the electric light of the observation room these looked dark green and black.

Lebret, despite himself, quailed at the sight. ‘Shall I try and reset the bone?’ he asked.

‘What are you asking

me

for, Vichy?’ muttered Avocat, speaking without relinquishing his teeth’s grip on the belt. He was staring furiously at a spot on the ceiling. ‘I daren’t even

look

at the thing. Don’t you know first aid?’