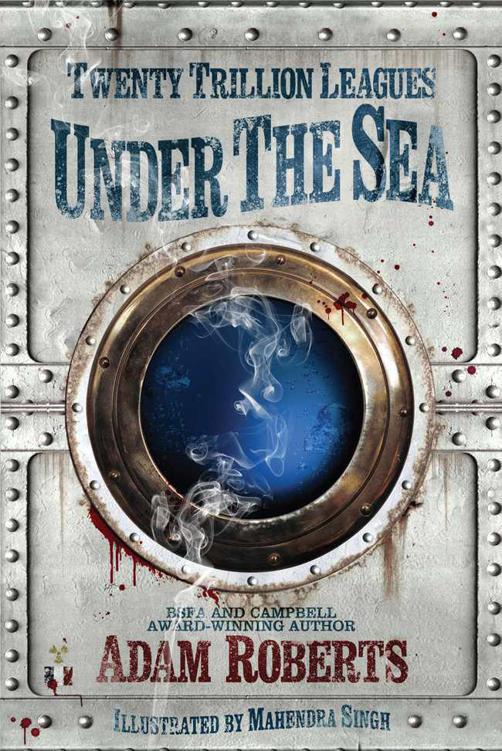

Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

GOLLANCZ

LONDON

They were the first

That ever burst

Into that silent sea …

CONTENTS

10 An Interview with Captain Cloche

28 The Arrival of the Plongeur

32 Twenty Trillion Kilometres Under the Sea

Also by Adam Roberts from Gollancz

Capitaine

Adam Cloche

Lieutenant de vaisseau

Pierre Boucher

Enseigne de vaisseau (de première classe)

Jean Billiard-Fanon

Second-Maître

Annick Le Petomain ‘Le Banquier’

Matelot

Alain de Chante

Matelot

Denis Avocat

Matelot

Jean Capot

Cook

Herluin Pannier

Chief engineer: Eric Castor

Observer: Alain Lebret. Reporting to the Minister for National Defence, Charles de Gaulle.

The scientists: Mr Amanpreet Jhutti, Mr Dilraj Ghatwala

On the 29th June, 1958, the submarine vessel

Plongeur

left the French port of Saint-Nazaire under the command of

Capitaine de vaisseau

Adam Cloche. The following day the

Plongeur

sank to the bottom of the ocean.

The submarine had travelled westward beyond the limit formed by the Atlantic continental shelf, and the depth of water at this place is considerably greater than three thousand metres. This can only mean that the submarine was lost with all hands. It is true, as some have pointed out, that the

Plongeur’

s design parameters – combining a plated-steel inner hull and a state-of-the-art ‘atomic’ propulsion system – enabled it to descend to unusual depths. But ‘deep’ in this context means only a maximum of one thousand metres or so. At three thousand metres the vessel would have been crushed to a mangled twist of metal. Even if the vessel had somehow managed to endure the unspeakable pressures of the profound deep, the sinking craft would, by this stage, have been dropping with such speed that the forward hull would have been cracked and shattered by collision with the rocky seafloor. And what else? Assume, if you choose, that they somehow, miraculously, survived the collision, and the

Plongeur

had settled onto the floor without shattering, and without being crushed by the abyssal pressures. What then? The melancholy truth is that the crew lacked the wherewithal to repair whatever malfunction in the main ballast tanks had brought about the disaster in the first place, and reascend. They would be condemned to a slow,

coffined extinction. Better, perhaps, to be snuffed out in a single mighty crunch!

The

Plongeur

was an experimental vessel, powered by a new design of atomic pile, and boasting a number of innovative design features. Its very existence was a national top secret. Accordingly, its melancholy fate went entirely unreported in the French media. As far as the world was concerned, its captain was no-one; its crew nameless.

In these unlucky circumstances, perhaps it was a blessing that, despite its unusual size – for the

Plongeur

was one hundred and sixty feet long, and displaced two thousand four hundred tonnes – the vessel was carrying only a small crew. The more the glory for them, the less the loss for France. Captain Adam Cloche was a veteran of the Free French Navy during the Second World War, and a man so much at home in the salt, estranging medium of the sea that even his friends wondered if he had any kind of life at all on land – where else would he die, if not beneath the waves? It was his proper place. Directly under Cloche’s command was Lieutenant Pierre Boucher, younger than his captain by a decade and a half, but an experienced sailor nonetheless. When he had been approached by the French Government to command this experimental submersible boat, Cloche had been permitted to choose any six officers and sailors. He personally approached Jean Billiard-Fanon to serve as

Enseigne de vaisseau

; and for Second Mate he recruited Annick Le Petomain, known to his friends as ‘Le Banquier’ for his skill at games of chance. Four Ordinary Seamen – Alain de Chante, Denis Avocat, Jean Capot and Herluin Pannier – were in turn recommended by Billiard-Fanon. But his request for a particular chief engineer – a certain Stefan Nevin of Calais, a veteran of the old war – was overruled by the powers that be. The new propulsion mechanism was top secret: for at its heart was an atomic pile, at that time a novelty in submarine power. An engineer with knowledge of such technologies, one Eric Castor, was assigned to the craft. More unusually still, two scientists from the team who had been developing the craft’s new technologies were also to accompany the

Plongeur

on its maiden voyage. These were: Messieurs Amanpreet

Jhutti and Dilraj Ghatwala, Indian nationals both. Cloche did not pretend to be happy about this. Even if (he argued) there were some potential advantage in having the inventors of the experimental technologies on board during the maiden voyage, the benefit was surely offset by the disadvantage of cluttering up the craft with landlubbers – and foreigners to boot. Worst of all, from the captain’s point of view, was the fact the presence on the

Plongeur

of an official ‘Observer’: Alain Lebret, reporting directly to the Ministry for National Defence. Cloche objected to the presence of these supernumeraries aboard his vessel; but his objections were overruled.

A crew of only nine was small for so large a craft, but the two-week voyage was expected to do no more than test the vessel’s new technological capacities. And despite the skeleton crew, space was tight aboard the submarine. Although it was large, its engines took up a disproportionate amount of the vessel’s central rear portions. Everything throughout was painted thickly with light blue paint, except for the engine itself which was painted red – it was strange, Cloche thought to himself, that there was no bare metal in the vessel anywhere to be seen. Still, it was certainly a well-

appointed

craft. Crew all had individual cabins, and a ‘scientific room’ was located fore, in which facilities for experimentation were laid out: a variety of technical accoutrements adorned this space. Most remarkable of all, a broad oval observation window was inset into the hull, and an observation chamber located below and fore of the bridge. When Captain Cloche was first shown round his new command, docked at Saint-Nazaire, he was – however much his imperturbable manner and large beard implied otherwise – especially dismayed to find this feature. ‘It must,’ he pointed out to the team who escorted him, ‘represent a weak spot in the pressure-robustness of the hull! How can it not?’ He was assured that steel plates, specially designed to lock together in an absolute seal, covered the six-foot-wide porthole when it was not being used for scientific observation. ‘I have served in a dozen submarines,’ Cloche said, shaking his head, ‘and commanded three, and I have never seen anything like it. Is this a warship of the French navy – or is it a lakeside pleasure skiff?’

‘May a warship not also have the capacity for observation and scientific enquiry?’ returned the official.

‘But – so

large

a porthole! The structure

must

be weaker at this place.’

‘The tolerances of the

Plongeur

are far in advance of comparable vessels,’ said the ministerial aide

‘In point of fact, the shipyards of—’ began a junior ministerial staffman.

The ministerial aide coughed loudly, and glowered at his subordinate. ‘There is no need,’ he said, brusquely, ‘to trespass upon the official secrets of the Republic by speaking of specific locations.’

‘Was the

Plongeur not

built here in the shipyards of Saint-Nazaire?’ asked Cloche, amazed.

That the ministerial aide would not be drawn further on this matter suggested to the captain that the answer to his question was that Saint-Nazaire was not the site of construction. But if not here – then where?

Of course the

Plongeur

was top secret. Although two years had passed since the US Navy had included nuclear submarines in its fleet, and despite the fact that, of course, France

was

a nuclear power, the existence of this advanced prototype of a radically new sort of submarine was closely guarded. It sailed without fanfare or notice, and it vanished into the great deep in the same manner. Nobody save a few senior officials and technicians knew of the

Plongeur’

s existence; and few amongst that select group mourned its loss.

It sailed from Saint-Nazaire before dawn. Midmorning, it essayed submerging for the first time. For most of the day of the 29th it performed a set of pre-arranged manoeuvres; testing the underwater and surface fitnesses of the craft. Through the night of the 29th and through the early hours of the 30th June it sailed west-northwest, leaving behind it the coast of northern Spain. Its last transmission was received before dawn on the morning of the 30th: Captain Cloche reported that he was about to take the craft down to its maximum dive depth. In the event the

Plongeur

passed far below that supposed ‘maximum’. No further transmissions were received.