Tudor (2 page)

Authors: Leanda de Lisle

11c:

Â

Edward VI as a Child, Hans Holkein the Younger, probably 1538 (© NGA Images, Washington, D.C.).

12b:

Â

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, Paul Delaroche, 1833 (© National Gallery, London).

12c:

Â

Mary I, Anthonis Mor, 1554 (© Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado).

15c:

Â

James VI of Scotland, aged twenty, Falkland Palace (© National Trust for Scotland Images).

15d:

Â

Lady Arbella Stuart aged 23 months, anon, 1577 (© National Trust Images/John Hammond).

The Past

: The Houses of Lancaster and York

For God's sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings;

How some have been deposed; some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

,

RICHARD II

ACT 3

,

SCENE 2

In fifteenth-century France it was believed that the English bore the mark of Cain for their habit of killing their kings.

1

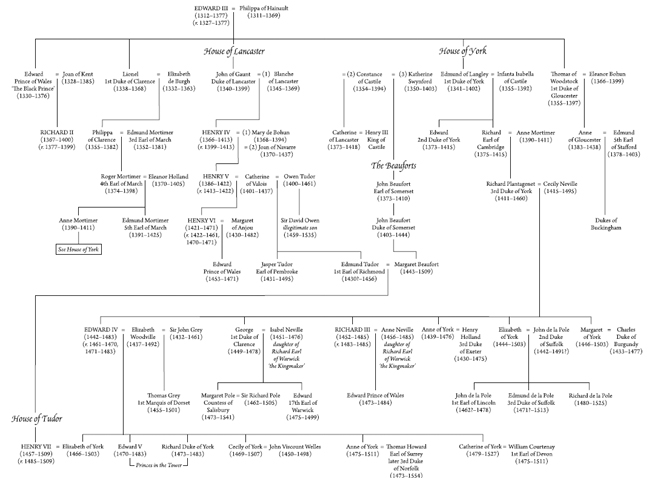

Before the slaughter of Richard III in 1485, when the Tudor crown was won on the battlefield of Bosworth, a series of English kings had been deposed and then died or disappeared in mysterious circumstances that century. The overthrow of the first of these, Richard II, in 1399, had brought a long-standing element of instability to the monarchy.

At that time, the paternal ancestors of the Tudors were modest landowners in north Wales â and even this status was lost the following year. In 1400 they joined a Welsh rebellion against Richard II's heir, the usurper Henry IV, first king of the House of Lancaster. The family was ruined after the rebellion was crushed, but eventually a child of the youngest son left Wales with his son to seek a better life in England. It was this man, Owen Tudor, who was to give the Tudor dynasty its name.

Looking back, Owen's life is that of a modern-day hero: a common man who lived against convention, often thumbed his nose at authority, and died, bravely, with a joke on his lips. Owen, however, is lost to the family story in histories of the Tudors that so often begin at Bosworth in 1485. So is the remarkable life of Owen's daughter-in-law, Lady Margaret Beaufort, whose descent from the House of Lancaster provided the basis for her son Henry Tudor's royal claim. Indeed his reign, as Henry VII, rarely merits more than a chapter or two before these Tudor histories propel us towards Henry VIII and the âdivorce' from Katherine of Aragon. Written by the children of the Reformation, the Reformation has become where the story of the âreal' Tudors begins; but the Tudors were the children of an earlier period, and their preoccupations and myths were rooted in that past.

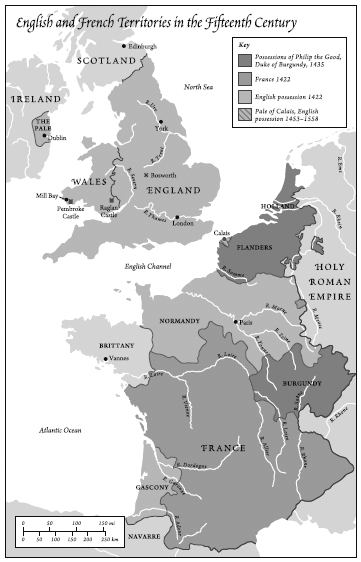

The famous mystery of the disappearance of the princes in the Tower in 1483, which turned Henry Tudor from a helpless exile into Richard III's rival overnight, becomes less mysterious when it is considered in the light of the culture and beliefs of the fifteenth century; the life of Margaret Beaufort also emerges in a more sympathetic light once we have recalibrated our perspective, and the actions of Henry VIII and his children can likewise be much better understood. England was not predominantly Protestant until very late in the Tudor period, and habits of thought were still shaped by England's long, and recent, Catholic past. Similarly, while the Tudors are often recalled in terms of a historical enmity with Spain, this too is history written with hindsight: the Armada did not take place until a generation after Elizabeth became queen. It was memories of the Hundred Years War with France that remained strong, and although the war that began with Edward III laying claim to the French throne had ended in 1453, over thirty years before Bosworth, it was to have a lasting impact on England's political character.

The English had not needed French land, as the country was under-populated after the Black Death. Successive English kings had been obliged to persuade their subjects to come into partnership with them

to help achieve their ambitions for the French throne. The result was that in England military service was offered, not assumed, and royal revenue was a matter of negotiation, not of taxation imposed on the realm. English kings were, in practical terms, dependent on obedience freely given, and that had to be earned. They had certain duties, such as ensuring peace, prosperity, harmony and justice (if a crown was taken from an expected heir or an incumbent monarch, the perceived ability to restore harmony within the kingdom was particularly important) and kings were also supposed to maintain, or even increase, their landed inheritance. England's empire in France had reached its zenith under Henry IV's son, Henry V, and his son Henry VI was crowned as a boy King of France as well as England. But then he lost the empire he had inherited. The humiliation of the final defeat at French hands in 1453 was not something England had recovered from even a century later, which is why the Tudors were devastated by the loss of Calais. It was the last remnant of a once great empire.

In England the loss of France in 1453 was followed by eighteen years of sporadic but violent struggle as the rival royal House of York fought for supremacy over Henry VI and the House of Lancaster. This was the period into which the first Tudor king, Henry VII, was born. It was still remembered in the reign of his grandson with horror as a time when âthe nobles as well as the common people were into two parts divided, to the destruction of many a man, and to the great ruin and decay of this region'.

2

It was the promise of peace, and the healing of old wounds, that was the

raison d'être

of the Tudor dynasty. The Pope himself praised Henry's marriage to Elizabeth of York in 1486 as marking the conciliation of the royal houses. This was symbolised in the union rose of red (for Henry VII and Lancaster) and white (for York). Although Henry VII denied he owed any of his royal right to his marriage and faced further opposition from within the House of York, the union rose became an immensely popular image with artists and poets in the sixteenth century.

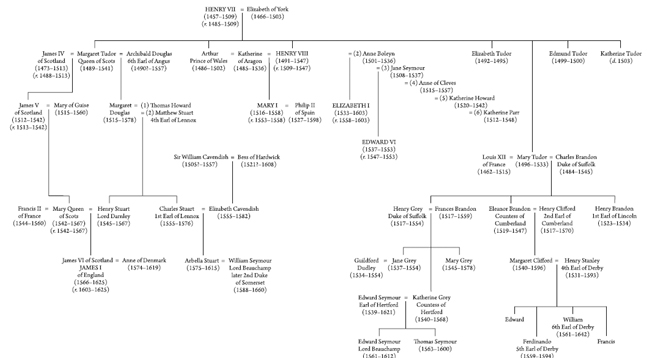

The key importance of the royal lines of Lancaster and York that

stretched back long before Henry VII, and which had nothing to do with his non-royal Tudor ancestors, has inspired the recent assertion that the Tudor kings and queens did not see themselves as Tudors at all, but as individual monarchs sprung from the ancient royal house, and that the use of terms such as âthe Tudor age' only creates a false separation from a hypothetical Middle Ages.

3

This is an important reminder that the Tudors did not exist in a time bubble, yet it is not the full story. It was well understood in 1603 that the Stuarts were a break from the family which had preceded them, and if Henry VII and his descendants did not see themselves exactly as a dynasty â a term not then used to describe an English royal line â they had a palpable sense of family.

4

It is there in Henry VII's tomb in the Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey, where he lies with his mother, his wife and three crowned Tudor grandchildren; it is also there in the Holbein mural commissioned by Henry VIII of the king with his parents and his son's late mother. The Tudors believed they were building on the past to create something different â and better â even if they differed on how.

The struggle of Henry VII and his heirs to secure the line of succession, and the hopes, loves and losses of the claimants â which dominated and shaped the history of the Tudor family and their times â are the focus of this book. The universal appeal of the Tudors also lies in the family stories: of a mother's love for her son, of the husband who kills his wives, of siblings who betray one another, of reckless love affairs, of rival cousins, of an old spinster whose heirs hope to hurry her to her end. âI am Richard II,' as the last of the Tudors joked bitterly, âknow ye not that?'

5

THE COMING OF THE TUDORS: A MOTHER'S LOVE