Trust Me, I'm Lying: Confessions of a Media Manipulator (16 page)

Read Trust Me, I'm Lying: Confessions of a Media Manipulator Online

Authors: Ryan Holiday

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Marketing, #General, #Industries, #Media & Communications

TACTIC #4

HELP THEM TRICK THEIR READERS

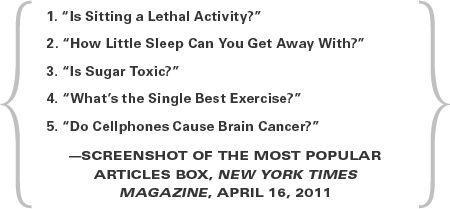

ARE LOADED-QUESTION HEADLINES POPULAR? YOU bet. As Brian Moylan, a

Gawker

writer, once bragged, the key is to “get the whole story into the headline but leave out just enough that people will want to click.”

Nick Denton knows that being evasive and misleading is one of the best ways to get traffic and increase the bottom line. In a memo to his bloggers he gave specific instructions on how to best manipulate the reader for profit:

When examining a claim, even a dubious claim, don’t dismiss with a skeptical headline before getting to your main argument. Because nobody will get to your main argument. You might as well not bother…. You set up a mystery—and explain it after the link. Some analysis shows a good question brings twice the response of an emphatic exclamation point.

I have my own analysis: When you take away the question mark, it usually turns their headline into a lie. The reason bloggers like to use them is because it lets them get away with a false statement that no one can criticize. After the reader clicks, they soon discover that the answer to the “question” in their headline is obviously, “No, of course not.” But since it was posed as a question, the blogger wasn’t

wrong

—they were only asking. “Did Glenn Beck Rape and Murder a Young Girl in 1990?” Sure, I don’t know, whatever gets clicks.

Bloggers tell themselves that they are just tricking the reader with the headline to get them to read their nuanced, fair-er articles. But that’s a lie. (I actually read the articles, and they’re rarely any better than the headline would suggest.) This lie is just one bloggers tell to feel better about themselves, and you can exploit it. So give them a headline, it’s what they want. Let them rationalize it privately however they need to.

When I want

Gawker

or other blogs to write about my clients I intentionally exploit their ambivalence about deceiving people. If I am giving them an official comment on behalf of a client, I leave room for them to speculate by not fully addressing the issue. If I am creating the story as a fake tipster, I ask a lot of rhetorical questions: Could [some preposterous misreading of the situation] be what’s going on? Do you think that [juicy scandal] is what they’re hiding? And then I watch as the writers pose those very same questions to their readers in a click-friendly headline. The answer to my questions is obviously, “No, of course not,” but I play the skeptic about my own clients—even going so far as to say nasty things—so the bloggers will do it on the front page of their site.

I trick the bloggers, and they trick their readers. This arrangement is great for the traffic-hungry bloggers, for me, and for my attention-seeking clients. Readers might be better served by posts that inform them about things that really matter. But, as you saw in the last chapter, stories with useful information are less likely to be shared virally than other types of content.

For example: Movie reviews, in-depth tutorials, technical analysis, and recipes are typically popular with the initial audience and occasionally appear on most e-mailed lists. But they tend not to draw significant amounts of traffic from other websites. They are less fun to share and spread less as a result. This may seem counterintuitive at first, but it makes perfect sense according to the economics of online content. Commentary on top of someone else’s commentary or advice is cumbersome and often not very interesting to read. Worse, the writer of the original material may have been so thorough as to have solved the problem or proffered a reasonable solution—two very big dampers on a getting a heated debate going.

For blogs, practical utility is often a liability. It is a traffic killer. So are other potentially positive attributes. It’s hard to get trolls angry enough to comment while being fair or reasonable. Waiting for the whole story to unfold can be a surefire way to eliminate the possibility for follow-up posts. So can pointing out that an issue is frivolous. Being the voice of reason does also. No blogger wants to write about another blogger who made him or her look bad.

To use an exclamation point, to refer back to Denton’s remark, is to be final. Being final, or authoritative, or helpful, or any of these obviously positive attributes is avoided, because they don’t bait user engagement. And engaged users are where the money is.

GETTING ENGAGED WITH CONTENT

Before objecting that “user engagement” is a good thing, let’s look at it in practice. Pretend for a second that you read an article on the blog

Politico

about an issue that makes you angry. Angry enough that you

must

let the author know how you feel about it: You go to leave a comment.

Here’s how it went for me the other day:

You must be logged in to comment, the site tells me. Not yet a member? Register now. When I click, a new page comes up with ads all across it. I fill out the form on the page, handing over my e-mail address, gender, and city, and hit Submit. Damn it, I didn’t type the

CAPTCHA

right, so the page reloads with another ad. Finally I get it right and get the confirmation page (another page, another ad). Now I check my e-mail. Welcome to

Politico!

, it tells me: Click this link to validate your account. (Now they can spam me later with e-mails with more ads!) Registration is now complete, it says: another page and another ad. I’m asked to log in, so I do. More pages, more ads, but now I can finally share my opinion with the author. I am “engaged.”

This is how it is everywhere. It might take as many as ten pageviews to leave a comment on a blog the first time. The

Huffington Post

makes a big show of asking users to rate its articles on a scale from one to ten. What happens when you do that? It shows you another page and another ad. Or when you see a mistake in an article and fill out the Send Corrections form? Well, first they’ll need your e-mail address, and then they ask if you want to receive daily e-mails from them.

When you do this, you are the sucker. The site doesn’t care about your opinion; it cares that, by eliciting it, they score free pageviews. I just got tired of being toyed with and decided to use this system to my advantage.

The best way to get online coverage is to tee a blogger up with a story that will obviously generate comments (or votes, or shares, or whatever). This impossible maze of pageviews is so lucrative that bloggers can’t help but try to lure readers into it. Following that logic, when I whisper to a blog about something disgusting that Tucker Max supposedly did, what I am really doing is giving the writer a chance to invite the readers to comment with “Eww!!!” or “What a misogynist!” I’m also giving Tucker’s fans a chance to hear about it and come to his defense. Nobody involved actually cares what any of these people think or are feeling—not even a little bit. But I am giving the blog a way to make money at their expense.

YOU ARE BEING PLAYED

A click is a click and a pageview is a pageview. A blogger doesn’t care how they get it. Their bosses don’t care. They just want it.

*

The headline is there to get you to view the article, end of story. Whether you get anything out of it after is irrelevant—the click already happened. The Comments section is meant to be used. So are those Share buttons at the bottom of every post. The dirty truth, as Venkatesh Rao, the entrepreneur in residence at Xerox, pointed out, is that

social media isn’t a set of tools to allow humans to communicate with humans. It is a set of embedding mechanisms to allow technologies to use humans to communicate with each other, in an orgy of self-organizing…. The Matrix had it wrong. You’re not the battery power in a global, human-enslaving AI, you are slightly more valuable. You are part of the switching circuitry.

1

As a user, the fact that blogs are not helpful, deliberately misleading, or unnecessarily incendiary might exhaust and tire you, but Orwell reminded us in

1984

: “The weariness of the cell is the vigor of the organism.”

So goes the art of the online publisher: To string the customer along as long as possible, to deliberately

not

be helpful, is to turn simple readers into pageview-generating machines. Publishers know they have to make each new headline even more irresistible than the last, the next article even more inflammatory or less practical to keep getting clicks. It’s a vicious cycle in which, by screwing the reader and getting screwed by me, they must screw the reader harder next time to top what they did before.

And sure, sometimes people get mad when they realize they’ve been tricked. Readers don’t like to learn that the story they read was baseless. Bloggers don’t like it when they discover I played them. But this is a calculated risk bloggers and I both take, mostly because the consequences are so low. In the rare cases we’re caught red-handed, it’s not like we have to give the money we made back. As Juvenal joked, “What’s infamy matter if you can keep your fortune?”