Trials of Passion (19 page)

Authors: Lisa Appignanesi

And so it continues over the next years. Christiana remains âtractable and amenable to the ordinary rules of the place', âquiet and orderly in her behaviour'; painting, etching, doing bits of embroidery. There is âno prominent indication of insanity'; she is âfree from actively insane indications'. Yet immediately, as if this moral fault were a signal of insanity, comes the sting in the tale the hospital notes tell: she is still âvain and frivolous' in her appearance and âin the general tone of her conversation and behaviour'. Christiana can only repeat her parody of everyday Victorian girlishness: it is her only remaining act. But once inside the walls of the largely working-class asylum, these characteristics of femininity garner disapproval. She is also too old for such vanities. She is meant to be penitent.

Yet with the passing of her obsession with Dr Charles Beard, can Christiana still be considered insane?

On 30 October 1880, she writes a letter to the Home Office in a neat and regular script. It is the only piece of her handwriting that remains. The letter itself is a cogent and moving memento to a troubled woman who has left no other personal trace.

Sir,

I venture to petition for my release from the Broadmoor Asylum. I have been eight years in confinement and am very anxious to regain my liberty. I earnestly trust that my conduct has been such as to gain for me the favourable regard of the Superintendent and those over me. I shall feel very grateful if you will kindly consider my petition and grant my release.

I remain Sir

Your humble Petitioner

Christiana Edmunds

The accompanying letter from Broadmoor notes that she âis at present tranquil and orderly in her conduct, but her mind is unsound'. On 4 November, there is a note from the Secretary of State saying that he âcannot comply with her appeal'. Christiana never appeals again, and as the years go by, her asylum notes grow briefer and briefer, testifying to her good health and âthe same vain indifferent irresponsible manner'. An entry of 1886 finds her âquiet and well behaved, cheerful and pleasant in conversation, but [she] is very vain, courts and desires attention and notoriety, pushes herself forward on all occasions, paints and tricks herself up for inspection and in almost her every act shows how little she appreciates the gravity of her crime or the position in which it has placed her'. Vanity â in Christiana's circumstances â has become a mark of insanity.

The hospital records do not reveal whether she responded in any way to her mother's death in 1893. She is âcheerful and contented' that year, and in the following year âemploys herself in painting and sketching'. Nor is there any note to mark a response to her sister Mary's death in 1898. Perhaps, in the way of things, they had long ceased to visit her. No change is noted in Christiana's condition until 1901, when signs of physical deterioration set in. Her sight is failing and there are backaches and various pains. In 1902 her symptoms improve as the annual ball approaches. After that, comes physical decline. Perhaps fittingly for a woman so concerned with appearances, time is

kind to her: increasingly impaired sight accompanies the passage of the years. In one of those little ironies of history, the Brighton house in which Christiana spent her most passionate years as the Borgia of Brighton, became a site of spectacle; a cinema.

On 22 November 1906, when she is scarcely able to walk without assistance and has spent over a week in the infirmary, a note records a conversation that could provide a fitting epitaph for Christiana Edmunds, a woman whom the delusions of passion led into criminality and an unintended murder. She is overheard talking to a patient who has âbeen in the habit of rendering her various little services':

E

[

dmunds

] â How am I looking?

A

[

friend

] â Fairly well.

E

â I think I am improving. I hope I shall be better in a fortnight, if so, I shall astonish them; I shall get up and dance â I was a Venus before and I shall be a Venus again!

We don't know whether Christiana rose from her sickbed to be the Venus she at least wished she had once been. In the way of those who today might be considered to suffer from a psychotic mental structure, wishes and fears for Christiana seemed to have acted as facts might for others. The Venus of Broadmoor gradually grew weaker and died at half-past five on the morning of 19 September 1907 at the age of seventy-eight. Charles Beard, who had left Brighton with his family soon after the trial and moved to Southport in Lancashire, outlived her by nine years, to die at the age of eighty-nine in London. His will shows him leaving £1889 18s. 2d., not a vast sum compared to Sir William Gull's £344,022 19s. 7d.

It is unlikely that Charles Beard knew of or marked the passing of the woman who had nurtured a morbid passion for him, one he had somehow provoked into murderous rage.

Perhaps Christiana Edmunds would have thrived a little better if she had been born at a slightly later date and in

belle époque

France. Propriety may have reigned here as well, but the public discussion

about the passions had a far greater openness to it, even in the courts, where the required âconfession', adapted from the Catholic inquisitorial system, could incorporate sexuality. Mind doctors, writers and that floating demi-monde â which might find itself part of the

beau monde

, the moneyed and respectable classes â even lawyers, all had a say about how love can drive you mad. Then, too, the earliest French alienists â who also had the excesses of the French Revolution in mind â had incorporated passion into the language of lunacy: there it would stay, through the course of subsequent upheavals, both social and individual.

âIf you asked eighty years ago if feminine virtue was part of universal humanism, everyone would have answered yes.'

Michel Foucault

A Hysteria of the Heart: The Case of Marie Bière

During the cold winter days and nights of the last month of 1879, thirty-one-year-old concert singer Marie Bière, partly disguised by a wide-brimmed hat and a lorgnon, stalked her lover through the streets of Paris. A revolver to hand, she followed him to dance halls and theatres. She hired a carriage and for hours staked out his apartment at 17 Rue Auber, a few steps from the newly completed Palais Gamier, home of the Paris Opera where Marie had once aspired to sing. Her despair was total. She could only wait, wait and watch. She was waiting for an opportunity to shoot.

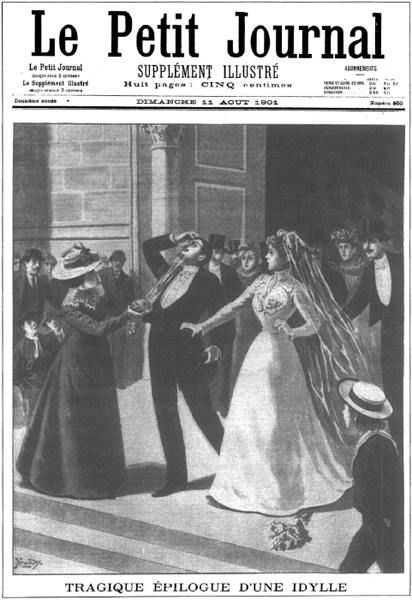

Around nine o'clock on the evening of 7 January, her chance came. Robert Gentien, accompanied by his new mistress Lucie Colas, a twenty-two-year old actress from the Palais-Royal, stepped out of the building. When Colas got into a carriage some way from the entrance, Marie hurled herself onto the street from her waiting vehicle and fired three shots at close range. After the first two shots, it was clear that Robert had been severely wounded in back and leg. The third bullet, fired as she was being stopped by passers-by, missed its target. To the police who were quickly on the scene Marie manifested no remorse. She regretted Robert wasn't dead, she stated emphatically. As soon as she could she would try to murder him again. He owed her a life.

What circumstances had led Marie Bière, a gentle, sensitive young woman, to these straits? What concatenation of overwhelming emotion and social impediments had toppled her into carrying out a raging and murderous act? The mind doctors were called in to examine her state. But if Marie Bière was mad â then her madness was contagious. It was a condition that spread through the

belle epoque

and affected more women than at any time before or since.

Marie Bière, wearing her stage name of Maria Biraldi, had met Robert Gentien in the elegant Atlantic resort of Biarritz over two years before. At twenty-eight, she was a lyric performer of some standing. Considered a child prodigy in her native Bordeaux, she had sung at a young age with the Philharmonic Circle, and had then trained at the Paris Conservatoire. Her voice had charm and clarity. But its power was not altogether sufficient for her to attain the heights she hoped for. She had aspired to sing Verdi and Meyerbeer at the famous Theatre-Italien, one of Paris's two leading opera companies: they had taken her on, but her ambitions were never fulfilled. The one major production she was scheduled for was cancelled for lack of funds. Nonetheless, at a time when any career for a young woman who also wanted respectability was a considerable achievement, Marie Bière certainly had one. She had regular engagements throughout the provinces. She appeared in famous resorts and spa towns â on the Riviera, at Pau, at the glittering Biarritz. Programmes headlining her still exist.

Despite her distinct ambition and sense of her own talent, Marie was strangely enough also well liked by her peers. There is something childlike about her. âShe was a good and gentle soul' until Robert Gentien led her astray, her friend and fellow artiste Mathilde Delorme said of her at the trial. She was certainly âno coquette', the kind of woman whose successes in the artistic sphere could only be measured by her success in the bedchamber.

In the police-archive files that detail the period of her investigation and trial, which also contain letters, her âconfession' and notebooks,

Marie Bière insistently repeats that she is no coquette, as if she is haunted by the very possibility. She is, she states, a respectable woman. She needs to distance herself both in the public eye and in her own mind from the courtesans, or

horizontales

, so prevalent at the time, particularly in the world of musical theatre and spectacle. One might even suspect that mixed up amongst the passionate motives that lead to her taking aim at Gentien is a sense that he stands for everything that she doesn't want herself to be: his gaze, his very existence, turn her into the woman of easy virtue she despises yet verges on being. If class and finances collude, the slippage for a woman between virtue and easy virtue is as quick as it is precipitous.

In

belle époque

France, attractive women of uncertain class could supplement their living, all the while making their way up the social hierarchy, by providing sexual favours for men of the middle and upper classes. It was a time when marriage for men came relatively late and was contracted on grounds of property and progeny, rather than love. Sex with unmarried women of their own class, whose chastity and innocence were essential attributes for marriage, was a near-impossibility. So from a young age, men often had recourse to prostitutes or their higher-status version, the courtesans. This was at one and the same time a clandestine and an acceptable form of behaviour. Repectable bourgeois mothers would far prefer their sons being initiated into sex by a woman of easy virtue to having them engage in the wrong kind of marriage. Keeping a courtesan had the added advantage that the woman might be âcleaner' than a prostitute â that is, uninfected by one of the many sexually transmitted diseases from gonorrhoea to syphilis that made the period's sexual relations a risky business.

For the kept women of the demi-monde â so sumptuously portrayed by Alexandre Dumas

fils

in

La Dame aux Camélias

, the basis for Verdi's opera

La Traviata

, and in the novels of Balzac, Zola and Proust, whose Odette rises from murky origins to the height of Parisian aristocracy â there might be advantages of independence and financial ease to be had from their status, which was at once shadowy and

showy. One of the many dangers, however, for both men and mistresses, was that while their arrangements were always most satisfactory if they provided a simulacrum of the passionate rituals and forms of romantic love, this could too often topple into the real thing. The unruly emotion then took over and played havoc with lives, since marriage, that sanctified âfor ever', was in most cases an impossibility. Families, inheritance, all of the bourgeois and indeed aristocratic world, stood in the way. Dumas's

La Dame aux Camélias

was based on his own enduring love affair with a courtesan whom he could neither give up nor marry.