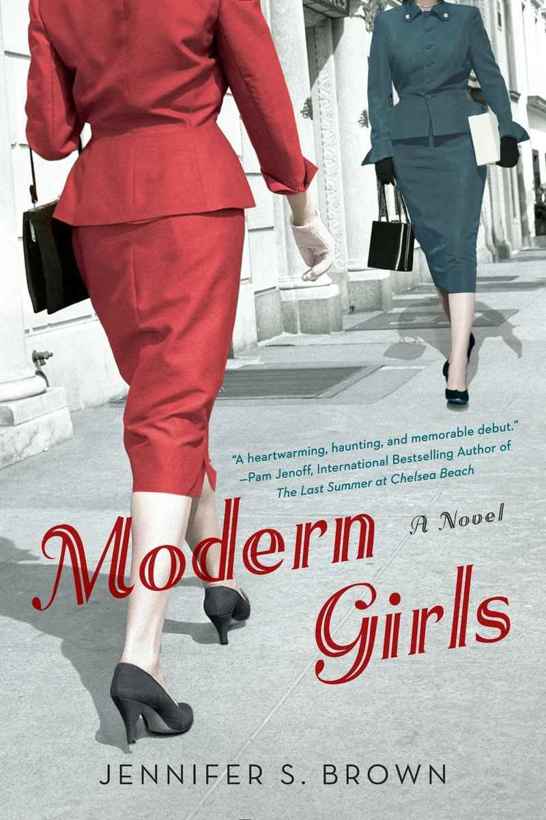

Modern Girls

Authors: Jennifer S. Brown

PRAISE FOR

Modern Girls

“

Brown pens the story of a Jewish immigrant mother and her unmarried daughter, both pregnant and neither planning on it, in 1930s New York City. The result is a thought-provoking tale of parents and children and the sacrifices they make for one another. Exploring our dreams and choices and the way they intersect to form our lives,

Modern Girls

is a heartwarming, haunting, and memorable debut.”

—Pam Jenoff, international bestselling author of

The Last Summer at Chelsea Beach

“Be prepared to lose yourself in a mother-daughter tale unlike any other. With one generation entrenched in the Old World and the other struggling to make her way in the new, Brown expertly handles the complex nuances of family secrets guarded along with impossible choices made in the name of love and honor. Original and unique, you’ll find yourself rooting for Dottie and Rose the whole way through.”

—Renée Rosen, author of

White Collar

Girl

NEW AMERICAN LIBRARY

Published by New American Library,

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

This book is an original publication of New American Library.

Copyright © Jennifer S. Brown, 2016

Readers Guide copyright © Penguin Random House, 2016

The author is grateful for permission to quote from “As we understand it, Goering and Goebbels are Hitler’s G-Men. Their job is to stamp out the pernicious churchgoing element” from August 17, 1935,

The New Yorker

, page 24, from “Of All Things” by Howard Brubaker/

The New Yorker

, copyright © Condé Nast. Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

New American Library and the New American Library colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

For more information about Penguin Random House, visit

penguin.com

.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-I

N-PUBLICATION DATA:

Names: Brown, Jennifer S. (Jennifer Sue), 1968–

Title: Modern girls/Jennifer S. Brown.

Description: New York, New York: New American Library, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015041939 (print) | LCCN 2015050012 (ebook) | ISBN

9780451477125 (paperback) | ISBN 9780698408524 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mothers and daughters—Fiction. | Jewish women—Fiction. | Life-change events—Fiction. | Choice (Psychology)—Fiction. | Jewish fiction. | Psychological fiction. | BISAC: FICTION/Historical. | FICTION/Jewish. | FICTION/Cultural Heritage.

Classification: LCC PS3602.R6987 M63 2016 (print) | LCC PS3602.R6987 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015041939

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

In memory of my grandparents, Bessie and Nathan Brown, who taught me that being a writer was a worthy aspiration, and for my parents, Peter and Carol K. Brown, who encouraged me to write even before I had anything to

say

Friday, August 16, 1935

MY lower back ached as I sat, shoulders rounded, hunched over like a number 9, on the wooden stool at my desk at Dover Insurance. I shifted my bottom, unable to find a comfortable position, as I picked up the statement atop the stack. I didn’t feel right: I had no fever, but my stomach sloshed and I needed another couple hours of sleep. The digits, though, drew me in, and I became absorbed in the dance of the numbers, the way they could come together and apart, making wonderful new combinations.

I didn’t initially notice the new girl standing over my desk. “Dottie,” she said, prompting me to look up. “Mr. Dover said to ask you if I had problems.” She thrust her ledger under my nose. “The totals aren’t matching up.”

I scanned the column, my eye drawn instantly to the error. “Here,” I said, pointing. “You’ve added the debits instead of subtracting.” My eye ran up and down the page again, and, handing her back the book, I said, “The total should be $1,365.43.”

She looked at the paper in her other hand, which listed the number she was supposed to match, and looked back at me wide-eyed. “How did you do that?”

I shrugged and she stared at me, bewildered, before walking away. I could calculate as fast as the tabulating machine. The skill was so natural that I was always surprised when others couldn’t do it.

I turned back to my statement. The numbers were a relief because the rest of my brain was stuffed with cotton balls.

What was wrong with me?

Even before work, the morning had begun inauspiciously. When I attempted to fasten my brand-new dress—the dress that Ma had spent two evenings refashioning so it looked like it came from the pages of

McCall’s

instead of the racks at Ohrbach’s—the back zipper stuck. Pulling off the dress, I could slide the zipper up and down just fine, but when I glided the fabric over my head again, it bunched gracelessly at the waist, and I needed to suck in my stomach as far as it would go. I made Alfie tug the pull closed. “Lay off the egg creams,” he’d said, unhappy at having to help his big sister get dressed. My body filled the fabric oddly, my bosom spilling out the top. Then, at breakfast, my bloated fingers were clumsy, and Ma scolded me when a glass slipped from my hand. I picked at the farina, which lay in a congealed blob in the bowl, then slid the dish over to my youngest brother, Eugene, who gobbled it down, but not before Ma spotted us. “My food isn’t good enough for your Midtown ways?” Ma said, and yet, she hurried me to the door: “Don’t be late for work.”

Trying to shake the fog from my mind, I copied numbers from the statements to the ledger. Mr. Renke submitted a quarterly premium of $11.82 for his accident insurance policy, which guaranteed $100 a month for up to twenty-four months should he become disabled due to an automobile accident, a calamity in an elevator, a wall collapsing, or any of the other misfortunes that might befall him. The numbers shimmied in my head, and while I double-checked the totals on the machine as my job required, I had no doubt they were correct. Math is so simple: A plus B always equals C.

Numbers comforted me, soothed me. They were absolute, unequivocal, the opposite of what I was feeling at that moment. Taking a deep breath, I put down my pen and looked toward the high windows. The sliver of sky visible was devoid of clouds, just a wash

of blue. A breeze from the fan in the corner ruffled my papers, and I put a hand atop them to keep them from flying away.

My dress constricted my stomach, making me squirm, which embarrassed me. I was no longer a schoolchild, but a mature woman of nineteen, and I certainly knew how to conduct myself in my place of work, which didn’t entail flopping in my seat like a marionette. Would I have to start reducing? Zelda did the grapefruit diet after having her baby, but Ma would never let me get away with that. Ma always tried to fatten me up even though this wasn’t the Old Country, where a woman was prized for a bit of flesh around the waist. This was New York City and all I wanted was to look like Claudette Colbert. My boyfriend, Abe, was dreamy—strong arms and devilishly handsome chocolate brown eyes—and while he thought I was beautiful no matter what, I didn’t want to test that by plumping up like a matzo ball in broth.

The next statement: Mr. Norquist paid $12.65, the monthly premium on his $3,000 life insurance policy. I flipped to the correct page in my ledger, found the column, and entered it. Three thousand dollars. What couldn’t I do if I had $3,000? Abe and I would be able to afford not only to marry and rent an apartment, but to furnish it with the finest trousseau out of

House & Garden

, and I would have no worries and a wardrobe from Saks.

My eyes skated over the room, watching the girls at work. Irene, as tiny as my seven-year-old brother, Eugene, typed letters to those delinquent on their payments. Florence dawdled, inputting numbers as I did, although three times more slowly, her pen looping in lazy circles. The other girls worked diligently, if not always precisely, only occasionally glancing at the clock or daydreaming while looking out the window. Our head bookkeeper, Mr. Herbert, had quit a week before, so an idle loll enveloped the room, and the tabulating machines weren’t clacking as quickly as they normally did.

I picked up the next statement and tried to revel in the numbers, in the slippery feel of a

three

, the kiss of a

two

, the hiss of a

six

. But I was so aware of my body, of the way it filled my dress; I couldn’t get comfortable.

Irene passed my desk as I pulled the fabric from my waist, trying to stretch it out a bit.

“Are you feeling all right?” she whispered. In the quiet room, though, her voice echoed. None of the other girls paid any mind.

“I’m just feeling out of sorts,” I said, trying discreetly to pull up my stockings a bit. “I don’t know why.”

“Maybe it’s your time,” she whispered even lower.

“My what?” I asked, in a normal voice.

Irene’s face washed in a warm blush. Leaning into me, she spoke into my ear. “You know. Your monthly.”

I nodded. “Perhaps.”

Irene set down the papers on Mr. Herbert’s former desk and returned to her own.

That must be it,

I thought. My monthly. I scooted the papers aside and looked at the calendar blotter on my desk. When was the last time I’d had my courses? Was I due?

My pen idly swirled in the air above the numbers. It was August 16.

Let’s see. . . .

I didn’t recall having it in July, but skipping a month wasn’t unusual.

The pen froze.

But what about June? Did I have it in June?

Beads of perspiration formed on my forehead. I looked up and around the room to see if anyone noticed the consternation that must have shown on my face, but all the girls were involved in their own work, their own daydreams. What did I do in June? Abe and I went to the theater twice and the café once. We picnicked in the park with Linda and Ralph. We swam and played baseball at Camp Eden.

Think, Dottie, think!

No. Not once did I need to excuse myself to take care of things.

Returning to the calendar, I stared. June was clean.

I chewed on the end of the pen hard enough that I cracked the celluloid. My brain flew frantically back in time, back to

May, back to the one weekend I

hadn’t

been with Abe. That was May 24. I counted. May 24 to August 16. Eighty-four days. Twelve weeks. The bloated fingers. The burgeoning bosom. My choking waist. May 24. And since then, not a sign of my courses.

Act normal,

I told myself, picking up the next form. If need be, I could work by rote. Copy numbers from statement into ledger. Add the credits. Subtract the debits. My hands made the motions while my mind desperately sought to make reason. One night. That’s all it had been: one night. A fight between me and Abe. A night alone at Cold Spring. But then, I hadn’t exactly been alone, had I? If I had, I wouldn’t be haunted by that night. I tried to take breaths to calm myself. My hand was quivering, causing droplets of ink to splatter on the desk. I set the pen in the inkwell and placed my palms flat on the surface to steady them.

Slowly exhaling, I sat frozen, until my body settled. The most important thing was to act normally. The stack of papers on my desk was finished. My reputation as a worker meant standing up and moving to Mr. Herbert’s former desk to retrieve another stack.

After scooping up new papers, I turned to go back to my desk, self-consciously placing my hand over my belly, as if to shield it, even as I knew there was nothing to be seen. I caught Florence’s eye. She looked at the papers in my hands and rolled her eyes. She used to tell me to slow down; my work was going to make the rest of them look bad. I tried at first—I wanted Florence and her girls to like me—but I soon realized Florence was never going to be friends with the Jew in the office, and to work slowly was boring. My cheeks flushed, and I was sure Florence could see behind the papers, could read my secret as easily as I read the numbers. I felt exposed, humiliated.

My mind raced: Had it really been twelve weeks? I was careless in my counting of days, irregular in my time. Nothing unusual.

But twelve weeks?

Even I should have noticed that by now. And what would I tell Abe?

Sitting back at my table, I vowed to get through as many

statements as I could before the lunch bell chimed. I needed the reliability, the honesty of the numbers.

I let myself drown in numbers—premiums for accident insurance, life insurance, fire insurance: $12.34, $7.56, $27.92. The minute my mind wandered from the ledgers, I forced it back: $34.23, $7.91, $43.34. So lost was I that I missed the ringing of the bell and didn’t realize it was noon until the babble of the girls’ chatter broke my concentration. They gathered their clutches and hats to go out for food as I sat dumbly at my desk. I never accompanied them, but I longed to today, anything to keep these thoughts from my mind. But going out to lunch with them was an impossibility. The girls thought me cheap, chalked it up to my being a Jew. I always said to them, if I had an extra forty cents, it would look so much nicer as a hat on my head than a meal I’d forget in an hour. The truth, though, was the food around the Midtown office was all

treif

, so Ma packed me a kosher lunch each morning. I was the only girl from the East Side working at Dover—the others were Italians, Irish, and Germans who commuted from Brooklyn and Queens.

I had no desire to eat, but I had to maintain appearances, so I made the motions of pulling out my lunch pail and unwrapping my sandwich. On her way to the door, Florence wrinkled her nose at the food on my desk. “What in heaven’s name is that?”

The sandwich looked particularly unappetizing. But I coerced a smile and said, “Pickled calf’s tongue.”

“Ew. Is that Yid food?” The girls behind her giggled.

“It’s scrumptious,” I said, keeping the smile plastered on my face. With great show, I picked up the sandwich and took a large bite. “Mmmm,” I murmured, trying to sound enthusiastic. Ma’s doughy wheat bread stuck to my upper palate, but I managed to give Florence a full-mouthed grin while trying to dislodge the bread stuck on my teeth with my tongue. Normally Ma’s sandwiches were delicious, but that day the tongue was slimy and the

bread heavy and grainy. I swallowed, the food rebelling on its way down, and said nothing more.

Florence’s eyes narrowed, and with a sniff, she turned on her little green ankle-strapped heel, straightened her hat, and left the office, her coterie of coiffed sheep trailing behind. I could hear them bleating down the hall as they headed to the Automat for lunch.

My stomach lurched, so I put down the sandwich, nauseated by the sight of it. I was about to toss it in the wastebasket when the front door of the office opened and Mr. Dover walked in. Florence would be annoyed to have missed him. She—and a number of the other girls—had a thing for the boss.

“Ah, Dorothea,” Mr. Dover said, approaching my desk.

“Mr. Dover,” I said, nodding my head. Did he notice how my leg trembled?

He spied the food on my desk and said, “Please, don’t let me interrupt your lunch.”

“No interruption, sir,” I said.

“Please. Eat your sandwich. I want to chat, but I’d feel terrible if I disrupted your lunch break.” Sitting on a stool, he gave me a paternal smile, as he removed his fedora and placed it on the table beside him.

Feeling trapped, I once again picked up the sandwich and choked down a bite. I gave Mr. Dover a wan grin. Making sure I swallowed completely before speaking, I said, “Delicious.” My stomach roared its disapproval.

Mr. Dover chuckled. Perched as he was, he looked oversized. His body didn’t fit at the desk that was the right size for the petite Irene. Row after row of tables and stools filled the room. At each table sat a tabulating machine or a typewriter and books with loose-leaf ledger sheets. I often thought we looked like overgrown schoolchildren at our desks, whispering, working, behaving impishly.

“So, Dorothea,” Mr. Dover said. His face was handsome, even with the receding hairline. Those chiseled cheeks, deep-set blue

eyes. No wonder the girls were mad about him. Of course, he didn’t hold a candle to Abe. Besides, Mr. Dover was a

shaygetz

. I could no more fathom mooning over a non-Jew than I could imagine eating a ham sandwich. “You have a talent for numbers, don’t you?”