Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (56 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

Her first examination paper is on philosophy, and the first question is “What is courage?” She quickly writes, “This is courage,” picks up her bag and coat, and leaves the examination hall. She receives an “A” grade on her paper and is accepted to the college of her choice.

A

sk Marilyn: Not long ago, you printed a letter from a girl who said her philosophy teacher gave a test that consisted of one question: “Why?” I liked your disapproving answer, but I’m surprised you didn’t mention that the story is an urban myth.

—Trister Keane, Brooklyn, N.Y.

It’s no myth—as you’d know if you read my mail. Many people wrote to relate their own distressing experiences taking this “test.”

Some had answered “Because” and received no credit because the teacher said the correct answer was “Why not?” Others had answered “Why Not?” and received no credit because the answer was “Because.” One person answered “Just because,” earning only partial credit and a detailed explanation of why her reply fell short of the ideal. But all had one feeling in common: They hoped their teachers saw my column that week. (And a few were going to forward it to them, “just to be sure”)

A

final exam had just one question: “Write the best possible final exam question for this course, then answer it.”

One student immediately wrote, “The best possible final exam question for this course is ‘Write the best possible final exam question for this course, then answer it.’”

I

n the end, you really never know what they’re looking for” [on graduate school entrance exam essays], the first woman said wearily. “There’s this famous Yale application question, ‘Ask something and then answer it.’ So this guy writes, ‘Do you play the tuba?’ and he answers, ‘No.’ And he gets accepted.”

“That,” the second woman said dismissively, “is an urban myth.”

These are a sampling of the many stories about supposed tricky questions and answers among college faculty and students. The version of “Which tire?” came from David W. Stultz of Nineveh, Indiana, in 1995. Most versions that mention “Professor Bonk” set the story at Duke University where a chemistry professor by that name teaches and may actually have asked that question of two erring students. However, the story is widely told on many campuses about a variety of other subjects as well. My example of the “Why?” examination comes from Marilyn vos Savant’s

Parade

magazine column of March 29, 1992, but she originally discussed the story way back on May 26, 1991. I have heard of instances of professors using the “Why?” question, but never of any who based a course grade or final examination grade on the answer. In my humble opinion, these teachers were inspired by having heard this old campus legend during their own undergraduate days, and they asked the question more as a prank than a real test. The “What is courage?” example came from John Longenbaugh of Sitka, Alaska, in 1991; this is an international story that I’ve heard from New Zealand and Italy, as well as the United States and Canada. I’m told that the French version asks for a definition of

“L’audace,”

with the entire winning answer being

“L’audace—c’ést ça!”

In yet another version of the story, the requirement is to write a five-page answer; a student writes “This is courage” and attaches five blank pages. The “Write your own question” topic is used occasionally on exams by some instructors, but the student’s witty response quoted above, as I’ve heard it several times, is probably a legend. The story about the Yale application question is from “Interview Jitters at Graduate School,” by Susan Schnur in the

New York Times,

April 10, 1994.

Reprinted with special permission of King Features Syndicate

“The Second Blue Book”

I

did hear, just yesterday, of a student at an East Coast college who asked for two blue books during a final exam. When the test ended, he handed in only one. He had written a note on the first page and left the rest of the book blank. “Dear Mom,” it said, “Just finished Psych 101 and want to tell you that I love you.”

Taking the other blue book home, he completed the exam, with the help of his textbooks, and mailed it to his mother. His professor called to ask about the mixup. The student feigned astonishment, then dismay. Retrieving the mailed blue book from his mother, he turned it in and, yes, got an A.

Quoted from Jon Anderson’s article on scams published in the

Chicago Tribune

in December 1990 and reprinted elsewhere the same month. In most versions of this classic campus legend the student writes a longer letter to his mother, lavishly praising the professor and the course. Then he asks his professor to verify his story by calling or writing his mother and arranging a swap of the two blue books. There are other blue book scam stories, two of which I quote in

The Mexican Pet

from a 1970 article. Students should not try this ploy in their own examinations, since most professors have heard the stories before, and the rest are likely to figure out on their own what the student is up to. As for examinations in general, here’s a well-known professorial principle: If you say “This is important” the A student writes it down. If you write it on the blackboard, the B student writes it down. If you say, “This is very important,” and write it on the blackboard, the C student writes it down. And if you say, “This will be on the final exam,” the D student asks you to repeat it.

In a sense,

all

urban legends are at least partly true, for as folklorist Linda Dégh has pointed out, these stories inevitably include “two kinds of so-called reality factors.” First, we find ample instances of what Dégh called “verifiable facts commonly known to be true” (like the existence of crime, pets, freeways, shopping malls, baby-sitters, college professors, embarrassing moments, sex scandals, and many other realistic details of everyday experience). Second, the legends incorporate “illusions, commonly believed to be true” (such as the operation of poetic justice, the likelihood of incredible coincidences, the possibility of someone mistaking a rat for a dog, the leaving behind of incriminating notes or photos by criminals, and the frequent flushing of unwanted reptile pets down the toilet). Put the facts and the illusions together with the skills of a good narrator, and you have believable, and even partly “true,” urban legends.

However, the truth factor in urban legends is most often simply a matter of people not questioning the teller’s details while trusting that narrator’s supposedly reliable sources. People believe an urban legend because the plot stays within the realm of possibility—no alien invaders, psychic powers, or sea monsters—and the storyteller is someone “who would never lie” and who can cite the authority of that famous “friend of a friend” to whom this remarkable thing actually happened. Parodying this rather naive attitude, a Boulder, Colorado, humor periodical called the

Onion

(which has the audacity to bill itself as “America’s Finest News Source”) in March 1977 published this item:

“URBAN LEGENDS TRUE,” SAYS FRIEND OF COUSIN’S ROOMMATE

Chicago—According to a study released Sunday by the friend of this one guy’s roommate, contemporary word-of-mouth folklore, or “urban legends,” are true. While not actually heard first-hand, the guy said, “Though typically met with skepticism, urban legends are almost always true. Like the one about the guy whose friends threw him a surprise party, but he was naked. I know for a fact that that’s a true story—my sister’s ex-boyfriend was at that party.” The guy also said that a child actually did die from consuming Pop Rocks candy with Coca-Cola, claiming that “it was in the paper.”

There are some who would respond to such a ludicrous statement that any comments about the truth or falsity of urban legends are moot, since legends are by definition untrue. Others would assert that since we are studying

stories,

not actual incidents, it makes no difference whether any of these stories—or parts of stories—happen to be true. In any case, in this chapter are discussed half a dozen stories that seem typically urban-legendary, but for which there is some actual truth component. Oddly, in most cases, it takes more length and detail to prove this point than it normally does simply to debunk a story.

“True Stories, Or At Least Good Urban Legends Dept.”

From Steve Orthwein at

The Edge:

A woman calls an import parts warehouse and asks for a 28-ounce water pump. “A what?” says the confused parts guy. “My husband says he needs a 28-ounce water pump.” “A 28-ounce water pump? What kind of car does it fit?” “A Datsun.” As he writes down “Datsun, 28 oz. water pump” the light in his head goes on. “Oh yes ma’am. We’ve got 28-ounce water pumps. We have 24-ounce and 26-ounce water pumps, too.” “Finally,” she says. “You’re the first place I’ve called that knew what I was talking about.” “Yes, ma’am. That’s because we’re a full-service parts warehouse. It’s our job to have the parts you need, like a 28-ounce water pump,” he says, smiling, as he jots down: customer pickup, Datsun 280Z water pump, part number….(In

Autoweek,

January 12, 1998.)

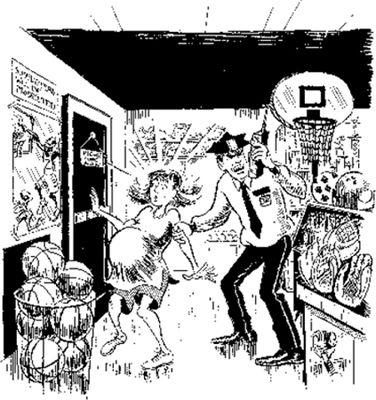

“The Pregnant Shoplifter”

A

n Arlington [Virginia] woman has filed suit against a Seven Corners sporting goods store, claiming a store employee forced her to prove she was pregnant because he thought she was shoplifting a basketball.

Betsy J. Nelson, 33, who was nine months pregnant when she went shopping at Irving’s Sport Shop last February, is seeking $100,000 in compensatory damages and $500,000 in punitive damages from the store, charging false arrest and negligence on the part of store employees, according to a suit filed in Arlington Circuit Court last week….

From an article by Nancy Scannell,

Washington Post,

July 19, 1985. I was pretty darn sure that this story was apocryphal when it started going around in 1985. Herb Caen of the

San Francisco Chronicle

likewise had commented, on September 12, 1985, “Too neat. Sounds like a fable.” I included a skeptical reference to the story in

The Mexican Pet.

I immediately heard from readers who sent me newspaper clippings—such as the one quoted above—providing names, dates, places, and other authenticating information. I admitted my error in

Curses! Broiled Again!

and now it’s time to close the books, so to speak, on this incident. Here’s the rest of the story: the

Washington Post

reported on November 19, 1986, that a circuit court jury in Arlington had rejected the claim of false arrest and negligence brought by Ms. Nelson, and the judge dismissed her claim for punitive damages. That’s the truth, but let me warn you that if you hear a story about the woman trying to steal a watermelon from a supermarket by hiding it under her dress and claiming to be pregnant, or the one about the frozen chicken hidden under the shoplifter’s hat, I’m 99 percent sure these are just urban legends.

“The Unsolvable Math Problem”

W

hat happened to George B. Dantzig in 1940, in his own words:

During my first year at Berkeley I arrived late one day at one of [Professor Jerzy] Neyman’s classes. On the blackboard there were two problems that I assumed had been assigned for homework. I copied them down. A few days later I apologized to Neyman for taking so long to do the homework—the problems seemed to be a little harder to do than usual. I asked him if he still wanted it. He told me to throw it on his desk. I did so reluctantly because his desk was covered with such a heap of papers that I feared my homework would be lost there forever. About six weeks later, one Sunday morning about eight o’clock, Anne and I were awakened by someone banging on our front door. It was Neyman. He rushed in with papers in hand, all excited: “I’ve just written an introduction to one of your papers. Read it so I can send it out right away for publication.” For a minute I had no idea what he was talking about. To make a long story short, the problems on the blackboard that I had solved thinking they were homework were in fact two famous unsolved problems in statistics. That was the first inkling I had that there was anything special about them.

A

s reported by Rev. Robert H. Schuller in a 1983 book:

Let me tell you about myself. My name is George Danzig [

sic

], and I am in the physics department at Stanford University. I’ve just returned from Vienna as the American delegate to the International Mathematics Convention, appointed by the President. I was a senior at Stanford during the Depression; we knew when the class graduated, we’d all be joining unemployment lines. There was a slim chance that the top man in class might get a teaching job, but that was about it. I wasn’t at the head of my class, but I hoped that if I were able to score a perfect paper on the final exam, I might be given a job opportunity.

I studied so hard for that exam, I ended up making it to class late. When I arrived, the others were already hard at work; I was embarrassed and just picked up my paper and slunk in to my desk. I sat down and worked the eight problems on the test paper and then started in on the two that were written up on the board. Try as I might, I couldn’t solve either one of them. I was devastated; out of ten problems, I had missed two for sure. But just as I was about to hand in the paper, I took a chance and asked the professor if I might have a couple days to work on the two I had missed. I was surprised when he agreed, and I rushed home and plunged into those equations with a vengeance. I spent hours and hours, and finally solved one of them. I never could get the other. And when I turned in that paper, I knew I had lost all chance of a job. That was the blackest day of my life.

The next morning I was awakened by a pounding on the door. It was my professor, all dressed up and very excited. “George, George,” he kept shouting, “you’ve made mathematics history!” Well, I didn’t know what he was talking about. And then he explained. I had come to class late and had missed his opening remarks. He had been encouraging the class to keep trying, not to give up if they found some of the problems difficult. “Don’t put yourself down,” he had said. “Remember there are classic, unsolvable problems that no one can solve. Even Einstein was unable to unlock their secrets.” And then he had written two of these unsolvable problems on the blackboard. When I came in I didn’t know they were unsolvable. I thought they were part of my exam, and I was determined that I could work them properly. And I solved one! It was published in the

International Journal of Higher Mathematics,

and my professor gave me a job as his assistant. I’ve been at Stanford for forty-three years now…. Dr. Schuller, I’m just going to ask you one question. If I had come to class on time, do you think I would have solved that problem? I don’t.

S

chuller’s version as presented to pastors in 1983:

Speaking of mathematics, Robert Schuller, of Chrystal [

sic

] Cathedral fame tells a story about sitting on a plane next to a fellow with his nose in a book…. Schuller said he wrote books on Possibility Thinking but admitted that they probably had nothing in common as “in mathematics it doesn’t matter whether you are a possibility thinker or an impossibility thinker. Two plus two equals four regardless of whether you are a negative or a positive person.”

“Well, I’m not so sure about that,” his seat partner interrupted him. “Let me tell you about myself…” etc.

H

ow Schuller’s version got back to George Dantzig (again, in his own words):

The other day, as I was taking an early morning walk, I was hailed by Don Knuth as he rode by on his bicycle. He is a colleague at Stanford. He stopped and said, “Hey George—I was visiting in Indiana recently and heard a sermon about you in church. Do you know that you are an influence on Christians of middle America?” I looked at him amazed. “After the sermon,” he went on, “the minister came over and asked me if I knew a George Dantzig at Stanford, because that was the name of the person his sermon was about.”

The origin of that minister’s sermon can be traced to another Lutheran minister, the Reverend Schuler [

sic

] of the Crystal Cathedral in Los Angeles. Several years ago he and I happened to have adjacent seats on an airplane. He told me his ideas about thinking positively, and I told him my story about the homework problems and my thesis. A few months later I received a letter from him asking permission to include my story in a book he was writing on the power of positive thinking. Schuler’s published version was a bit garbled and exaggerated but essentially correct.

H

ow a Texas churchgoer reported it:

My mother related this to me as she had heard it in a sermon in Fort Worth, Texas. A young man in college was working very hard to prove himself, studying ’til all hours to learn as much as was humanly possible. He was taking a course in upper-level math that he was very much concerned about for fear that he would not be able to pass. He studied for the final so long and so hard that he overslept on the morning of the final.

He ran into the examination room several minutes late and found three equations to solve on the blackboard. The first two went by rather easily, but the third one was impossible. He worked frantically on it until, ten minutes short of the deadline, he found a method that worked and finished the problem just as time was called. He was very disappointed in himself that such a seemingly easy problem had taken him so long to figure out.

Then, that evening he received a phone call from his professor. “Do you realize what you did on the test today?” he practically shouted at the student. “Oh, no,” thought the student, “I didn’t get the problem right after all.”

“You were only supposed to do the first two problems,” the professor continued. “The last one was just one that I wrote to show an equation that mathematicians since Einstein have been trying to solve, without success. And you just solved it!”

Although I traced the path of this academic story in

Curses! Broiled Again!

I presented there only paraphrases of the various retellings of George Dantzig’s experience. The full verbatim accounts quoted here are well worth comparing in order to note the numerous variations of detail that have occurred. Dantzig’s accounts above of the class and of the meeting with Schuller are quoted from an interview published in the September 1986 issue of the

College Mathematics Journal.

Schuller’s version, undoubtedly also included in at least one of his televised programs, is quoted from Michael and Donna Nason’s 1983 book

Robert Schuller: The Inside Story.

In the same year, the Schuller story was presented to pastors in the September issue of the newsletter

Parables, etc.

The Texas minister’s version of the story was sent to me in 1982 by Marc Hairston, then a student at Rice University in Houston. For the record, here are a few corrections and clarifications: 1. George Dantzig is in the Department of Operations Research at Stanford; 2. Schuller’s “Crystal Cathedral” is in Garden Grove, California; 3. Dantzig’s solution of the first problem was published in

Annals of Mathematical Statistics,

vol. 22, 1951; and 4. Dantzig, at the time of the incident, was a beginning graduate student at Berkeley. When I met Professor Dantzig—“the father of linear programming”—at Stanford in 1991, he explained several points in the story that were still vague to me even after receiving his 1987 letter in reply to my queries. The second problem he had solved, for example, was published jointly with Abraham Wald in 1951; Wald had arrived at a solution independently and by a different method. This whole incident provides a fine example of how a personal experience, repeated several times in different contexts, and circulating in both printed and oral sources, may eventually achieve a new life of its own as a folk story, although, as Dantzig gently pointed out to me, I should have titled it more correctly as “The

Previously

Unsolvable Math Problem.” In 1989 Dean Oisboid of Los Angeles sent me this variation of the story that he heard in the early 1970s from a junior high school mathematics teacher: