Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (48 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

And so our camping story ends.

Moral:

Never drive more than 300 miles a day on a camping trip; 50 to 200 miles if on an overnight or weekend camping trip.

Moral:

Study a road map and become familiar with every turn before starting each day’s drive.

Moral:

Never ride in the back of a camper or trailer; sit up front with the driver.

Moral:

Have rear-vision mirrors on both sides of a recreational vehicle. And use them constantly. Know what’s going on behind you as well as in front of you.

This much embellished and expanded version of a popular urban legend constitutes the preface of Dan and Inez Morris’s 1973 book

The Weekend Camper.

In

The Vanishing Hitchhiker

I quote a long oral text of the story collected by folklorist Ronald Baker in Indiana, and I trace the legend in published, filmed, recorded, and word-of-mouth sources back to the early 1960s. Some versions of the story from the South describe the husband finally catching up with his wife, putting on some pants, but neglecting to zip his fly; when they stop at a restaurant, he notices his error and hastily zips up, catching the tablecloth in the zipper, which leads to further slapstick results. In some English versions of the story it is the wife rather than the husband who is left behind, and in an Australian version sent to me in 1989 by Adrienne Eccles of Unley, South Australia, a character referred to as “Auntie,” clad only in her panties, is accidentally left behind. She hitches a ride with a motorcyclist: “He put her on the pillion seat, and they gave chase. A short time later, Uncle was astounded to be overtaken by a motorcycle ridden by a leather-clad bikie and his nearly nude wife.” All of these stories are similar to a legend of the 1940s about a scandalous incident that supposedly happened during an overnight train trip. In “The Cut-Out Pullman Car,” a businessman clad only in bathrobe and slippers went from the club car after his nightcap to the sleeping compartment of a young woman whom he had met on the train. When the businessman woke up the next morning, he was in the wrong car and the wrong city; the woman was gone, and so was his billfold. His clothes were still in his own compartment in another Pullman car far away in the city to which he had been traveling. Possibly “The Cut-Out Pullman Car” was updated to fit our post-railroad era of travel.

“The Stunned Deer—or Deer Stunt”

W

ith the assistance of one of Quincy’s finest, I have acquired a copy of the actual recording of an emergency call for help, as it was received by an ambulance service near Kansas City.

Remember, this is the transcript of a real call. Some of the more colorful words have been replaced in order to make it readable for the entire family.

Other than that, each word is as it was spoken that night. Believe it or not.

Dispatcher: Fire and ambulance, where do you need us?

Caller: Hello?

Dispatcher: Yes?

Caller: Who is this?

Dispatcher: This is the ambulance emergency line. Do you have an emergency?

Caller: I…I need an ambulance.

Dispatcher: Who is this?

Caller: Joe.

Dispatcher: OK, Joe, where do you need us?

Caller: I’m in the (stupid) phone booth.

Dispatcher: OK. What’s the address there?

Caller: Hold on.

Dispatcher: OK. Sir, did you call through 911?

Caller: Uh…yeah…no.

Dispatcher: OK, Joe, I need a location. What street are you on?

Caller: Uh, I’m in a (stupid) phone booth at the Stop and Go. That’s it. I’m at the (stupid) Stop and Go. On uh, on uh…wait a minute. Hucks…where’s the (stupid) street? Hucksmith, Corville and something…at the (stupid) Stop and Go.

Dispatcher: Hucksmith, Corville and what?

Caller: Hold on…yo.

Dispatcher: uh huh.

Caller: Let me see…Carfee, Coofee…

Dispatcher: Coffee?

Caller: There you go. There you go. I’m in the (stupid) phone booth. Let me tell you what. I’m going down the (stupid) road, driving my car, minding my own (stupid) business, and a (stupid) deer jumps out and hit my car.

Dispatcher: OK, sir, are you injured?

Caller: Let me tell ya. I get out, and pick the (stupid) deer up. I thought he’s dead. I put the (stupid) deer in my back seat, and I’m driving down the (stupid) road, minding my own business. The (stupid) deer woke up and bit me in the back of my (stupid) neck.

It bit me and done kicked the (stuffing) out of my car. Now I’m in the (stupid) phone booth.

The deer bit me in the neck. A big (stupid) dog came and bit me in the leg. I hit him with the (stupid) tire iron, and I stabbed him with my knife.

I got a hurt leg and the (stupid) deer bit me in the neck. And, the dog won’t let me out of the (stupid) phone booth because he wants the deer.

Now who gets the deer? Me or the dog?

Dispatcher: OK, sir, are you injured?

Caller: Yeah! The (stupid) deer bit me in the neck. Hold on, the (stupid) dog is biting me. Hold on…(doggone it) get out of…hold on…the (stupid) dog is biting my (posterior). Hold on.

Unfortunately, the tape ends here. So, we never learn whether the driver gets the deer, the dog gets the deer, the deer gets the driver, or the dog gets the deer and the driver.

And, I don’t know if anybody ever got an ambulance.

Have a good day outdoors.

From John Landis’s “Outdoors” column in the

Quincy (Illinois) Herald-Whig

for December 6, 1992. Elaine Viets, columnist for the

St. Louis Post-Dispatch,

in 1989 traced this story to an actual incident that occurred in 1974 in Poughkeepsie, New York. Viets even spoke to the officer who took the call. Numerous tapes circulate in police departments all over the United States, all purporting to be copies of the actual emergency-line call about the stunned deer. However, the tapes vary greatly in language and details. Landis’s Kansas City version, for instance, tells essentially the same story as Viets’s obtained from New York, but none of the wording matches. I discuss the entire tradition, including other stories about different stunned creatures awakening inside cars, in my book

The Truth Never Stands in the Way of a Good Story.

“We live in

a time besotted with Bad Information,” wrote Joel Achenbach in the

Washington Post

(December 4, 1996). He continued, “It’s everywhere. It’s on the street, traveling by word of mouth. It’s lurking in dark recesses of the Internet. It’s in the newspaper. It’s at your dinner table, passed along as known fact, irrefutable evidence, attributed to unnamed scientists, statisticians, ‘studies.’”

I would add this to Achenbach’s list: Bad Information is also found on thousands of copies of anonymously produced fliers that are handed around neighborhoods and workplaces, posted on bulletin boards, sent home with schoolchildren, scouts, and even preschoolers, and faxed, mailed, and E-mailed to a wider audience.

Most of these fliers are bogus warnings against some kind of dire threat. Such warnings were formerly typed or even handwritten, but all the warning fliers nowadays seem to be produced on computers and duplicated in copy shops. Often they are printed out in all capital letters sprinkled with spelling errors and other typos, and sporting a generous use of exclamation points. Sometimes these fliers are reproduced on the letterheads of companies or institutions or they may cite supposedly valid sources, lending them an authoritative look and feel. Routing information directing the fliers around the office is common, as are handwritten additions like “Warning!!!” or “Please Read and Circulate!!!” or “This Is Not a Joke!!!”

What makes such documents a part of

folklore

—technically “Xeroxlore” or “photocopylore,” as folklorists dub them—is that they are anonymous, variable, unverifiable texts that are stereotyped in form and content. Like most urban legends, there’s often a modicum of Good Information included, but unlike true legends, these warning notices contain no well-developed narrative content; in that respect, they are perhaps more like rumors (unverified reports) than legends (too-good-to-be-true “true” stories).

Patricia A. Turner of the University of California at Davis, in her landmark book of 1993,

I Heard It Through the Grapevine: Rumor in African-American Culture,

provides a good recent example of the interplay of oral and printed dissemination of Bad Information. One of the many rumors Turner collected was this: “Tropical Fantasy [a fruit-flavored soft drink] is made by the Ku Klux Klan. There is a special ingredient in it that makes black men sterile.” The same rumor of a sterilizing additive was spread concerning the Church’s fried chicken franchise, and the same supposed KKK connection was made with both Church’s Chicken and Troop, a once-popular brand of athletic wear. Besides word of mouth, this typical piece of Bad Information (

none

of these assertions is true) also circulated in New York City among the African-American community in an anti-Fantasy-soda flier that was headed “Attention!!! Attention!!! Attention!!!” and framed at the bottom margin with “You Have Been Warned. Please Save the Children.” The main text of the flier referred to supposed validation of the claims on the “T.V. Show 20/20” and stated that Fantasy and two other brands were manufactured by “The Klu., Klux., Klan.”

ATTENTION!!! ATTENTION!!! ATTENTION!!!

.50 CENT SODAS

BLACKS AND MINORITY GROUPS

DID YOU SEE (T.V. SHOW) 20/20???

PLEASE BE ADVISE, “TOP POP” & “TROPICAL

FANTASY” ALSO TREAT SODAS ARE BEING MANUFACTURED BY THE KLU.. KLUX.. KLAN..

SODAS CONTAIN STIMULANTS TO STERILIZE THE BLACK MAN, AND WHO KNOWS WHAT ELSE!!!!

THEY ARE ONLY PUT IN STORES IN HARLEM AND MINORITY AREAS YOU WON’T FIND THEM DOWNTOWN…. LOOK AROUND….

YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED

PLEASE SAVE THE CHILDREN

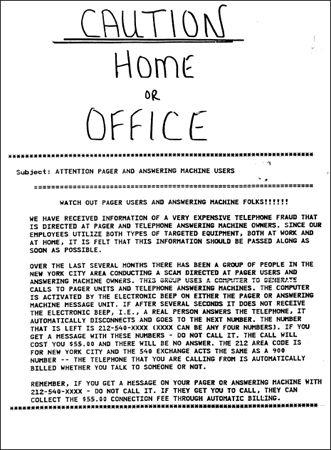

Here is another example of Bad Information in a similarly bogus warning flier, but in a completely different context. This example was taken from their company’s bulletin board and sent to me by Laurie Catlender and Bruce MacIsaac of Scarborough, Ontario, Canada, in 1993:

What lends this example some credibility is that there are some genuine and well-documented forms of telephone and pager fraud. But several things mark this warning as a likely piece of photocopied Bad Information. Consider, for example, the vague “We Have Received Information,” the handwritten heading, the lack of source information, and especially the highly doubtful description of how such a scam might operate (especially the assertion that you would be billed whether the telephone is answered or not!).

Personally—warnings or no warnings—I never return calls to any long-distance numbers left on my answering machine unless I know the caller

and

really want to talk to him or her. If someone wants to notify me that I’ve won the lottery or inherited a fortune, then let them send me a letter, or better yet show me the money. And whenever anyone complains that I didn’t return a call, I just say that my machine must have malfunctioned, which is true about half the time anyway. (This paragraph, I assure you, is

Good

Information.)

As I was writing this chapter I came across the following apt passage in Stephen Jay Gould’s regular “This View of Life” column in

Natural History

magazine (December 1997/January 1998): “An odd principle of human psychology, well known and exploited by the full panoply of prevaricators, from charming barkers like Barnum to evil demagogues like Goebbels, holds that even the silliest of lies can win credibility by constant repetition. In current American parlance, these proclamations of ‘truth’ by xeroxing…fall into the fascinating domain of ‘urban legends.’”

“Pushing Him Off the Wagon”

You know these chips, or tokens, that Alcoholics Anonymous gives out to mark your period of abstinence? I have one on a string around my neck: a yellow plastic poker chip with “9 months” printed on one side and “God grant me the serenity” on the reverse.

Well, I want to warn you that there are some bars that will give you free drinks for these chips—one drink per 30-day chip is the usual offer. They want to turn reforming alcoholics into good customers again.

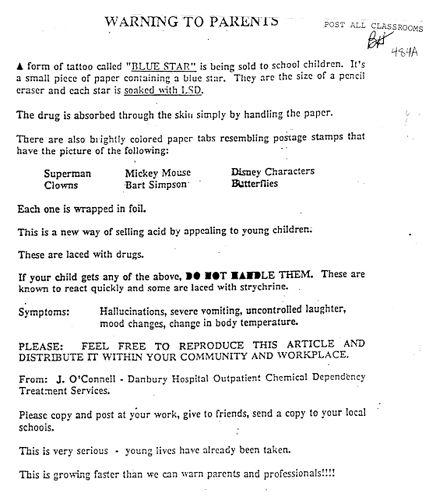

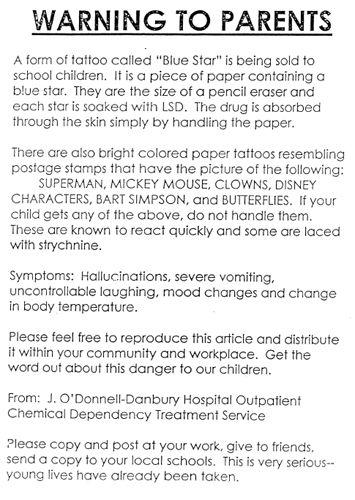

“Blue Star Acid”

From my thick file of examples of this particular bogus warning I selected two, both sent to me in 1996. The first, which “hung for years in a prominent position in this school system,” came from Isaac P. Espy, Jr., Athletic Director of the City Schools of Scottsboro, Alabama, who commented, “this bad boy has urban legend written all over it.” The second example “turned up in a local bank” and was sent by Mary Mosley of Fulton, Missouri, who wrote, “I smelled an urban legend right away.” Variations on this flier have been around since the early 1980s, possibly based on a garbled unauthorized reprinting of an actual police notice of that era, and they continue to proliferate. “Blotter acid”—absorbent paper soaked in LSD—has been produced since the 1960s, and all kinds of pictures, symbols, and texts have been printed on the paper, but these “tabs” have never existed in the form of tattoos. Investigative journalists and drug-enforcement officials have consistently denounced such fliers, and the reference to “J. O’Connell” (or “O’Donnell”) is as bogus as the rest of the information. A 1991 press release from the Michigan State Police discounts all of the warning’s claims: “While LSD does exist in paper form, it is NOT casually sold to children, it is NOT laced with strychnine, and it does NOT cause death in users. It is NOT a new drug, nor is it epidemic.” A police narcotics supervisor quoted in the same release puzzled, “We don’t know who generated the original letter or why it continues to recycle every year. It is like a chain letter that started 10 years ago and won’t go away.” What happens, I assume, is that whenever some well-meaning citizen comes across a copy of an older notice and believes it to be authentic, he or she decides to make duplicates on a photocopy machine and to send it circulating once again. Since the warning is dramatic, frightening, and quite convincing to an unaware reader, on and on it goes. Translations of essentially the same bogus warning have circulated internationally. What a long strange trip it’s been!

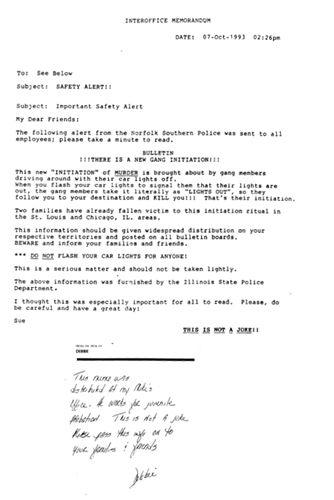

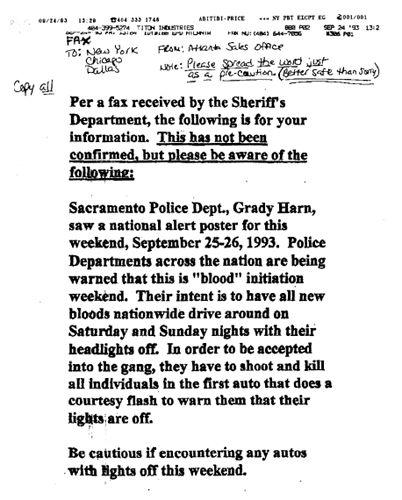

“Lights Out!”

Two typical examples of a bogus warning that circulated widely across the United States in literally thousands of copies from the summer of 1993 until about the end of that year. The interoffice memo, presumably based on a police report, moved from “Sue” on to “Debbie,” who added a handwritten Post-it note explaining that she got it from her husband, who got it at his place of employment, on to “Kelley,” who added a note—“This reeks of urban legend to me!”—and sent it on to me. The faxed warning mentions four major U.S. cities in the header. No such gang initiation—either planned or actually carried out—could be found by any of the numerous journalists and law-enforcement officials who tried to investigate the warnings. “Blood Weekend” in September 1993 came and went without anyone being killed for flashing headlights. There is no “Grady Harn” in the Sacramento Police Department. The “Lights Out!” warning created intense fear and outrage among American motorists because the “courtesy flash” to warn other drivers that their headlights are off is a well-established custom that is regarded as a good turn, not a threat. Feeding into the scare were both the known increase in gang violence and publicity about a growing number of “road rage” incidents. I discuss this bogus warning in detail in my book

The Truth Never Stands in the Way of a Good Story.