Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (34 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

A hospital spokesman knew nothing of an exchange of tabs for dialysis minutes….

First, a May 19, 1965, story in the

Spokane, (Washington) Spokesman-Review;

second, “Keep Tabs on Your Cans,” a brochure issued by Reynolds Aluminum and the National Kidney Foundation in 1988; third, an October 30, 1992, article by Thomas Korosec from the

Fort Worth Star-Telegram;

fourth, a January 3, 1997, article by Teresa Wood from the

Fort Walton Beach (Florida) Daily News.

Rumors that huge numbers of otherwise useless things can be redeemed for direct health benefits for needy patients have circulated for at least forty years. The companies and hospitals named in the rumors are often perceived as heroes until the falsity of the stories is revealed; then they become the villains. The first article above anticipates the eventual focusing of all such rumors on the opening tabs on aluminum drink cans; as kidney dialysis machines became available in the 1970s, pull-tabs-for-dialysis became the standard version. Despite the development of opening tabs designed to remain attached to cans, and despite the fact that costs of dialysis are largely borne by government programs and health insurance, the rumors persist. Year after year newspapers report individuals and groups that have amassed enormous quantities of pull tabs, believing that they can be exchanged directly for time on dialysis machines. Often these efforts are combined with an elementary-school teacher’s desire to illustrate for a class how a million of something would look. The unintended lesson that all of these collectors learn is that aluminum is worth its weight in…aluminum. It would make more sense to recycle the entire can, or in states with a can deposit, to redeem the cans at collection centers. Complicating this whole picture is the establishment of several genuine pull-tab collection campaigns since 1989 to raise money for various health concerns; but

all

of these efforts conclude by simply selling the aluminum to recycling centers. Since most of these programs ask people to mail in their pull tabs, it is considered impractical and unsanitary to collect the whole cans. Nobody seems to be bothered by the cost of postage versus the very low value of pull tabs, and nobody seems interested in a program in which donors would recycle their aluminum in their home communities and then simply mail a check to the sponsors. Somehow, pull tabs by the millions and millions seem to have captured people’s imaginations, and many people are willing to believe that doctors will not turn on dialysis machines to save the lives of poor little children until enough pull tabs arrive at the hospital. Question: what do people think the hospitals want with the pull tabs?

“The Body in the Bed”

M

y aunt told me this story. She said that it really happened to her nephew’s friend. It seems that the friend and her husband were staying in the Excalibur Hotel in Las Vegas. There was a slight but unpleasant odor in the room. They checked the room for rotting food, unflushed toilets and the like, but found nothing. Being that it was in the wee hours of the morning, and they were exhausted, they decided to retire for the night and tell the management in the morning. When they woke up, the stench had become unbearable. They complained to the management. It was then discovered that in the box springs lay the corpse of a prostitute. They had literally slept with a prostitute!

From Curtis Minato of Los Angeles, writing me in August 1991. This was a very popular story in 1991 and ’92; sometimes the body was said to be that of a Mafia hit victim. Most versions ended with the hotel management—at either the Excalibur or the Mirage—cancelling all charges on the room, or even promising the victims a free room for life if they will keep their experience quiet. Both the lingering smell of death and the freebies are reminiscent of the much older “Death Car” urban legend. In 1988 the decomposed body of a murder victim was found under a bed in an Oceanside, New Jersey, motel room, but, except for the report of a bad smell, this case was different from the Las Vegas legend. Instead of being a luxury hotel, the New Jersey business was described in news stories as one that “attracts a ‘transient type’ of clientele who often stay only a few hours at a time.” According to newspaper reports, in March 1994, after German tourists complained of a bad smell in a motel room near the Miami International Airport, the decomposed body of a woman was found under the bed. Five months later, according to further news stories, another decomposed body was found in a Fort Lauderdale, Florida, motel room by—would you believe?—another group of German tourists. As unlikely as these last two cases seem, I read it in the newspaper, which is better than hearing it on the grapevine. No further body-in-bed urban legends seem to have emerged since 1992.

“The Cabbage Patch Tragedy”

I

n the Christmas seasons of 1983 and 1984, Cabbage Patch Kids, those moon-faced soft dolls, were the hottest toys of the season. You did not merely buy a Cabbage Patch Kid, you adopted one, and you got the papers to prove it.

Eventually some of the dolls got broken, or run through the wash, or chewed on by the dog. When the doll’s “parent” sent the damaged “kid” back to the factory, she got in return…

- A letter of condolence?

- A death certificate?

- A bill for the funeral?

- The “kid’s” remains in a tiny coffin, ready for burial?

- A citation for child abuse?

Answer: None of the above. The doll’s manufacturer, Coleco Industries (sometimes misunderstood to be “Conoco”), provided repair services at set fees for their dolls, but no funerals, coffins, death certificates, etc. A spokeswoman in the Cabbage Patch public relations department in Georgia, when contacted by a reporter in November 1984 about the stories, sighed and said, “Has that story surfaced again? I thought we buried it. No pun intended.”

There’s a wonderful

continuity in certain legends of the workplace. Over and over again through the years—according to the stories—the working stiffs have found ways to one-up and frustrate the bosses. In his 1981 book

Land of the Millrats,

folklorist Richard M. Dorson collected this classic example in a steel mill of northwestern Indiana in the mid-1970s, calling it “the classic folk legend of mill thievery”:

John was an immigrant laborer from eastern Europe who worked in the mills. And every afternoon when leaving work he trundled out a wheelbarrow with his work tools, covered with straw. The gate guards were suspicious of John, and they always examined the wheelbarrow carefully, poked under the straw, but never found anything except the tools, which clearly belonged to him. So they had to let him go through.

So this went on day after day, year after year. Finally the day came for John’s retirement. He had worked thirty years in the mill. So, as he is leaving on his last day, trundling out his wheelbarrow, the gate guard said to him: “All right, John, we know you have been stealing something. This is your last day; we can’t do anything to you now. Tell us what you have been stealing?”

John said: “Wheelbarrows.”

Forty years earlier, during the Great Depression, a similar story was told about another eastern European worker, this one a Jewish salesman of “pazamentry” named Sam Cohen. (Pazamentry, the storyteller explained, “is the decoration that’s added to a garment”—lace trim, embroidery, ribbons, fancy buttons.) Again the worker is a trickster who gains the last laugh on management just as he’s about to retire. This beautifully elaborated version of the payback story was told by Jack Tepper of Brooklyn to folklorist Steve Zeitlin and appears in Zeitlin’s book

Because God Loves Stories

(1997).

Well after forty years Sam is going to retire, and he’s talking to another salesman, and he says, “What I really want to do is, there’s a Mr. O’Connell who owns a dress house, and he would never buy anything from me ’cause he hates Jews. And to me, the high-light of my career, is before I retire I could sell him an order.”

So he goes to Mr. O’Connell to sell him an order. Mr. O’Connell looks at him and says very sardonically, “I hear you’re retiring, Cohen. You’ve been bothering me for years, and you know I don’t deal with Hebes. But, okay, you want an order, I’ll give you an order—token order.” He says, “You have any red ribbon?”

Cohen says, “Sure we got red ribbon. What width?”

He says, “Half inch.”

“We got half-inch ribbon.”

“You got it.”

“How much you need?”

“All you need is an order, right? Just to show you sold me. I want a ribbon that will reach from your belly button to the tip of your penis. That’s as big a piece of ribbon as I want.” And Mr. O’Connell throws him out of his factory.

Six weeks later, Mr. O’Connell goes to open up his factory, and in front of his door are five trailer trucks. And they are unloading thousands and thousands and thousands and thousands of yards of ribbon. He runs upstairs, gets on the phone, and says, “Cohen, you miserable animal, what the hell did you send me?”

He says, “Look Mr. O’Connell. Exactly what you asked me is what I sent you. My belly button, everybody knows where it is. You said till it reaches the tip of my penis. Fifty-five years ago I was circumcised in a little town outside of Warsaw, Poland….”

Legends like these portray the bad old days in the world of work, and sets of strict rules purporting to prove the bad side of the “good old days” are also passed around as anonymous photocopied folklore. These rule lists, like urban legends, have many variations. Usually the lists are claimed to date from the 1860s or ’70s; however, every copy I have seen of “The Good Old Days” is printed or typed in a modern format and never reported directly from an authentic century-old source. Most of them are claimed to be guidelines for the office workers in a “carriage shop.” Some of the lists have as many as a dozen entries, but here is a typical example with six items from Robert Ellis Smith’s 1983 book

Workrights:

Working hours shall be 7:00 A.M. to 8:00 P.M. every evening but the Sabbath. On the Sabbath, everyone is expected to be in the Lord’s House.

It is expected that each employee shall participate in the activities of the church and contribute liberally to the Lord’s work.

All employees must show themselves worthy of their hire.

All employees are expected to be in bed by 10:00 P.M. Except:

Each male employee may be given one evening a week for courting purposes and two evenings a week in the Lord’s House.

It is the bounden duty of each employee to put away at least 10% of his wages for his declining years, so that he will not become a burden upon the charity of his betters.

Smith credited the

New York Times

for these rules, which sounded impressive, so I looked up the referenced November 17, 1974, issue. All I found was the list itself, appended to a

Times

article about privacy; the list was credited to “a New York Carriage Shop, 1878.” The

Times

was probably merely reprinting as a sidebar a piece of contemporary photocopy lore, just as the

Boston Globe

once did with a similar list credited to “a carriage works in Boston” from 1872. I have further versions of “The Good Old Days” on file that modify the rules slightly to fit the jobs of warehouse workers, furniture-store employees, nurses, and teachers. Every one of them requires workers to save part of their wages so as not to be a burden to society and/or to their “betters.” And, curiously, most lists, whatever the occupation involved, make some reference to employees having to “whittle nibs” for their pens and bring some coal for the office stove. Is it possible that so many different businesses a century ago in scattered locations had parallel sets of strict rules? If so, then where are the specimens of actual dated documents listing these rules?

Not surprisingly, stories about the modern-day workplace are no easier to verify than are the stories claimed to be from the past. Take the story told to me a few years ago in Portland, Oregon. This time the venue is a jet airliner:

Supposedly, George Shearing, the blind jazz pianist, was flying from Los Angeles to Seattle. The flight made a brief stop in San Francisco. The pilot, a big jazz fan, went back to meet Shearing during the stopover. When the pilot offered to provide any service or assistance that the pianist might require, Shearing said that he’d appreciate it if someone would take his Seeing Eye dog out for a brief walk.

The captain himself was happy to oblige. He took Shearing’s guide dog out for a stroll on the tarmac next to the parked jet. When the other passengers saw their pilot walking to and fro with a guide dog, most of them deserted the flight. The plane was nearly empty on the hop to Seattle.

Or take this workers’ story from the contemporary world of computer manufacturing. It’s told among industrial engineers and quality-control specialists:

An American company needed some computer memory chips, so they placed an order with a Japanese company. The Americans specified an acceptance criterion of 0.2 percent defective, and they ordered 1,000 chips.

The order arrived in two packages. The larger package contained 998 perfectly good memory chips. The smaller package contained two defective chips with a note saying that they didn’t know why the company wanted two defective chips, but it was their policy always to meet customer requirements.

Work at any level has its characteristic folklore, usually including a few legends. When a former pizza delivery man told me about the time he delivered a hot pizza to a nude woman on a warm summer night in southern Michigan, I asked him how he knew she was nude, since he mentioned that he had not actually seen her. For two reasons, he replied. First, she had kept the door hooked on the locking chain and made him slip the pizza in vertically through the crack. Second, he had heard many stories from other delivery men about nude customers who had greeted delivery persons working for that company. Indeed, I myself subsequently heard several other accounts of pizza delivery to nude customers, and I was reminded of people in other legends who were said to have been caught at home in the buff by other service personnel—plumbers, meter readers, and carpet layers.

I don’t want to identify any particular company as the most frequent target of these tales, but I do think that something we folklorists call “The Goliath Effect” is operating. What this means is that the dominant company in any business tends to become the magnet for all legends told about particular products and services. That being true, and because such stories also spill over to smaller competitors, I would identify the pizza-delivery legends as exhibiting “The Domino Effect.”

I got another twist on pizza delivery in a letter from a reader in Australia. The writer had heard that the Goliath of the industry there (Guess who?) had an agreement with the city’s drug squad. Whenever a delivery person suspected that the people who had ordered pizza might be under the influence of drugs (“and especially if they ordered double anchovies”), then the driver would immediately notify local police to stage a raid.

Supposedly, in return for this reporting service, the pizza company’s drivers never received speeding tickets. Personally, I wouldn’t trust anyone who would order even a regular-size dose of anchovies on their pizza.

“Wheeling and Dealing”

A seaman who was steering the ocean liner

Queen Mary

across the Atlantic got bored one day and carved his initials on the wooden steering wheel. When the captain saw this, he ordered the seaman to pay for a new wheel.The seaman did as he was ordered, but after he paid for the wheel he stated that now it was his, and he disconnected it and took it to his cabin. The ship was helpless in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, and they had to beg the seaman for the wheel so they could bring the ship into port.

“The Rattle in the Cadillac”

L

et me tell you the moving saga of an almost perfect luxury car—a dream machine, but for a single irritating flaw due to sabotage on the assembly line. The car, so the story usually goes, is a sparkling new Cadillac, outfitted with every available option. But soon after purchasing it, the car’s wealthy owner discovers one feature that nobody wants—a persistent, unexplained rattle coming from somewhere in the car.

The owner returns the new car to the dealership again and again. Mechanics tune and retune the engine, tighten every nut and bolt, and lubricate everything that moves. But each time the owner pilots the big car back out onto the street, the rattle is still there, as loud as ever.

Finally, in desperation, the owner instructs the mechanics to dismantle the car completely, piece by piece, until they find the elusive rattle. When they remove the left-hand door panel they spot the problem. Inside the hollow door, a soda bottle is suspended by a string. As the car moves, of course, the bottle swings to and fro, bumping the inside of the door. The bottle contains a collection of nuts, bolts, and pebbles—and a note: “So you finally found it, you rich SOB!”

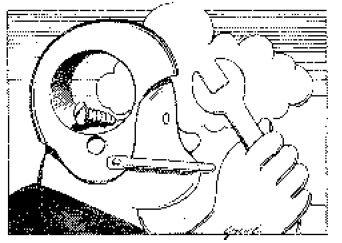

Illustration by Joe Goebel, copyright 1987, 1998

Some Caddy owners, it is claimed, have had the bottle and its contents framed as souvenirs of the odd incident. But, oddly enough, I’ve never seen such a display, or one of the alleged notes, although I’ve heard about them from many friends of friends of friends of the supposed car owners.

I retold this old story in a newspaper column released the week of August 8, 1988. In response to the column, W. K. Petticrew of New Castle, Delaware, wrote, “I have grown weary of hearing the soda-bottle-in-the-door-panel story; I’ve heard it

so

often since 1969 when I started ‘twisting wrenches’ for a living. The story has more holes in it than a hobo’s teeth.” Those holes, of course, are what make “The Rattle in the Cadillac” a bona fide urban legend that suggests how blue-collar autoworkers seek to gain revenge against the people who can afford the luxury cars they build. Sometimes the story is told about employees at an auto plant that is about to be moved or closed down; the workers played the prank to protest the loss of their jobs. This legend was given national prominence in 1986 by Brian “Boz” Bosworth, then a star linebacker at the University of Oklahoma, who claimed, in

Sports Illustrated’

s preseason football issue, to have encountered the prank while working at a General Motors plant in Oklahoma City during the summer of 1985. Boz’s anecdote raised the roof in Oklahoma City, and in Detroit, where GM executives denied that any such incidents of sabotage had occurred. Eventually Boz apologized, and a fellow plant employee added, “He heard a lot of auto war stories [but] we don’t even have any nuts or bolts in the part of the plant where Brian worked.”