Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (3 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

If you wanted to

invent new urban legends, you might start by imagining ways that people could be led astray by jumping to conclusions. Your UL characters could completely misinterpret, say, a faithful wife’s unexpected behavior, or a beautiful secretary’s intentions, or a pet’s sudden death. The poor schnook in your legend could then end up destroying his own new car, or disrobing for his office’s surprise birthday party, or sending her dinner guests to the hospital for an unnecessary stomach pumping. To prove not only that this principle governs some legends, but also that the stories themselves are much better than mere plot summaries, see the tellings of “The Solid Cement Cadillac,” “Why I Fired My Secretary,” and “The Poisoned Pussycat at the Party.”

All of the legends in this chapter—and many more—center on the natural human tendency to jump to conclusions even when the evidence is ambiguous. A couple of hot new stories follow this same logic, or illogic, if you will. Number one: A guy gets a new computer and calls the manufacturer’s technical support to complain that his cup holder is stuck. Cup holder? He mistook the function of the built-in CD-ROM tray. (I give the full story in the Introduction to Chapter 14, “Baffled by Technology.”) Number two: A new secretary told to order more fax paper for the office calls the supplier and asks them to fax her a few dozen sheets until the larger order can be filled.

Did many of the classic urban legends actually start that way? Frankly, my friends, I don’t know. After nearly two decades of collecting and studying this vibrant genre of modern folklore, I’m still pretty much in the dark about how such tales originate. It was the same with Bill Hall, a columnist for the

Lewiston (Idaho) Morning Tribune

, who wrote this a few years ago:

It’s a question as eternal as where dirty jokes come from: Where do those untrue stories of amazing things that allegedly happened to someone in your town come from?…The same stories surface and resurface over the years [and]…most of the people who spread the phony stories believe them to be true.

But if Bill Hall and I—and other journalists and folklorists—are unsure about the ultimate origins of urban legends, we agree on the likely process of how they develop in oral tradition, and this too involves faulty reasoning. Somehow a story gets started, and then, as Hall perceptively wrote:

It’s a funny yarn so it passes quickly from person to person. And each one accidentally embellishes it a bit—jumping to the conclusion, for instance, that it happened to someone right here in this town.

That Bill Hall heard urban legends way out in Lewiston, Idaho, hardly a metropolis, proves how widespread these stories are nowadays. And his apt observation of how “jumping to conclusions” works in the stories proves that human psychology operates similarly on modern legends wherever they are told. The human impulse in Bill Hall’s example is to make the stories more personal and local; in my view, we should also note the impulse to formulate theories even on bad premises.

Folklorists call the process of story reinvention in oral tradition “communal re-creation,” but describing it as simply passing stories along with an occasional teller jumping to the wrong conclusion will work just fine, too. You can easily imagine that’s what was going on in the invention and development of the following specimens.

“Miracle at Lourdes”

An Irish Catholic woman, because of poor health, traveled to France in order to visit the famous shrine to the Blessed Virgin Mary at Lourdes. The spring water there is renowned for its miraculous healing powers.

The woman became very tired during the long wait at the grotto for the blessing of the sick to begin. And since there happened to be an empty wheelchair among the crowds of pilgrims, she sat down in it for a rest.

As a priest finally approached to give the healing blessing, the woman stood up from the chair to meet him. And immediately when the people saw her rising, everybody started to claim that it was a miracle.

Crowds gathered around her, and they started to push and shove, wanting to touch her. In all this commotion, and with all the pushing and shoving, the woman fell and broke her leg. So the poor woman came home from Lourdes with a broken leg.

“The Truth Never Stands in the Way of a Good Story”

O

ne scorching day a woman pulled into a parking spot at a supermarket and noticed that the woman in the next space was slumped rigidly over her steering wheel holding one hand up to the back of her head. She felt concerned for the other woman, but went on with her shopping. When she returned to her car with her groceries, the other woman was still sitting in the same position—hand up to the back of her head and bent over her steering wheel.

So the first woman tapped on the window and asked if the other woman needed any help. Was she feeling all right?

“Please call 911,” she gasped, “I’ve been shot and I can feel my brains coming out!”

Then the first woman noticed a grey sticky substance oozing out between the other woman’s fingers, so she ran back into the store, phoned for help, and notified the store’s manager.

When the paramedics arrived they carefully pried the woman’s fingers from the back of her head, examined the injury, and checked the rest of the car. Then they started laughing. The paramedics explained that a canister of Pillsbury Poppin’ Fresh® biscuit dough on the top of her grocery bag in the back seat had exploded in the heat. The metal lid on the tube had struck the woman on the back of her head, and the top biscuit had shot out and stuck to her hair.

The sales receipt in the woman’s groceries showed that she had sat there for one and a half hours before anyone had stopped to offer help. The manager gave her a new can of biscuit dough.

This story became popular during the long, hot summer of 1995 and continued to circulate through the following year. A “joke” version developed on the Internet, beginning “Beware the Dough Boy. My friend Linda went to Arkansas last week to visit her in-laws….” The comedian Brett Butler, among other media personalities, delighted in retelling “The Biscuit Bullet Story,” sometimes as a supposedly true story. The “leaky brain” motif occurred in several old, traditional folktales, one of which may have mutated into the modern legend. I provide a complete history in

The Truth Never Stands in the Way of a Good Story.

“The Solid Cement Cadillac”

A

cement-truck driver cut through his own neighborhood one day while delivering a load of ready-mix, and he was surprised to see a new Cadillac convertible standing in his driveway. He parked his truck, sneaked up to the kitchen window, and spied his wife inside talking to a strange man.

Suspecting that his wife was cheating on him, the driver backed his truck up to the Caddy and dumped the full load of wet concrete into it. The Cadillac sank slowly to the pavement like the mother of all low riders.

That evening the man came home and found his wife hysterical, with the now-solid Cadillac being towed away. Through her tears she explained how that morning the dealer had delivered the new car that she was going to give her husband for his birthday. She had been scrimping and saving for years to buy him his dream car.

Technically, this legend should be titled “The Solid

Concrete

Cadillac,” since cement is merely the grey powder that, when mixed with aggregate [sand and gravel] and water, hardens into concrete. But “cement” is the folk term for the finished product. This story has circulated in many communities for decades, sometimes claimed to have happened locally as long ago as the 1940s. In an alternate version, the car was won in a lottery. An authenticated instance of an actual concrete-filled car was reported in the

Denver Post

in August 1960, but the car was a DeSoto, and there was no jealousy motive involved. A 1970 article in

Small World,

a magazine for Volkswagen owners, claimed that a prototype of the legend, involving a garbage-truck driver emptying his load into a Stutz Bearcat, was told in the 1920s, but we have no concrete proof of when and where this story originated.

“The Package of Cookies”

Who’s Sharing What with Whom?

A

woman was out shopping one day and decided to stop for a cup of coffee. She bought a little bag of cookies, put them into her purse, and then entered a coffee shop. All the tables were filled, except for one at which a man sat reading a newspaper. Seating herself in the opposite chair, she opened her purse, took out a magazine, and began reading.

After a while, she looked up and reached for a cookie, only to see the man across from her also taking a cookie. She glared at him; he just smiled at her, and she resumed her reading.

Moments later she reached for another cookie, just as the man also took one. Now feeling quite angry, she stared at the one remaining cookie—whereupon the man reached over, broke the cookie in half and offered her a piece. She grabbed it and stuffed it into her mouth as the man smiled at her again, rose, and left.

The woman was really steaming as she angrily opened her purse, her coffee break now ruined, and put her magazine away. And there she saw her own bag of cookies. All along she’d unknowingly been helping herself to the cookies belonging to the gracious man whose table she’d shared!

From

The Pastor’s Story File,

Number 1, November 1984, credited to a United Church of Christ minister from West Virginia who heard it from a missionary to Japan at a church conference. The chain of retellings, plus the certainty of other ministers adding the story to their repertoires, indicate one way that this popular legend has spread. Known in England since the early 1970s as “The Packet of Biscuits,” the story has endless variations. Sometimes the shared food is a Snickers or a Kit Kat candy bar, and often there is considerable social distance between the participants: a punk rocker and a little old lady, for instance, or a pair of high- and low-ranking military officers. British science-fiction author Douglas Adams incorporated the story into his 1984 book

So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish.

Another version of the story provided the plot of

The Lunch Date,

an Oscar-winning short film of 1990, and the legend separately inspired

Boeuf Bourgignon,

an independent Dutch film first shown in Europe in 1988. Ann Landers published a letter containing a Canadian version of this story in her November 11, 1977, column. In the May 25, 1998, “Metropolitan Diary” feature in the

New York Times

a reader reported yet another “Package of Cookies” incident with the same old familiar details, but this time supposedly having happened to the reader’s aunt. Obviously, this is too good to be true, so to avoid embarrassing her, I am not repeating the name of the contributor.

“The Tube on the Tube”

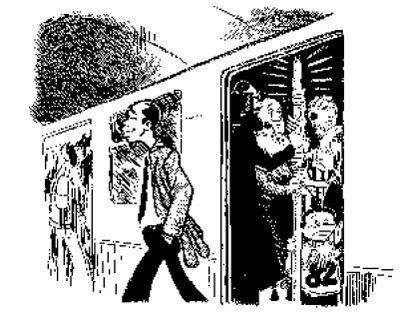

A

man working in a small office on an upper floor of a Manhattan skyscraper was exasperated one day when the lone fluorescent tube in his light fixture burned out. Rather than bothering the maintenance crew, who always gave him a hard time about fixing anything, he went out and bought a new tube and replaced the burned-out one himself.

Then he had the problem of disposing of the old tube: it was too long to leave in the wastebasket, and he didn’t want it there for the janitor to find. So he decided to carry the tube out of the building at quitting time and leave it in a Dumpster.

But he still had not found a Dumpster by the time he got to his subway station, so the man, holding the fluorescent tube upright—like a shepherd’s staff—hoping to disturb as few people as possible, boarded his homeward-bound car. As he rode, several other people got on, saw no open seats, and grabbed hold of the tube, believing it to be a pole in the subway car.

When the man reached his stop, several other hands were still gripping the tube, so he shrugged, released his own grip, and quietly left the car.

Although this is hardly a popular urban legend—I’ve heard it just a few times with little variation—it’s one of my favorite stories. My invented title fits London’s “tubes” better than New York City’s subways, but I have no evidence that it was ever told in England. In fact, several people told me they believe they read it in the “Life in These United States” section of

Reader’s Digest.

That’s no guarantee that the story has any truth to it, of course, and its details seem highly unlikely.