Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (9 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

“The Dead Cat in the Package”

I

n December of 1992 a friend of mine told me about two friends of a friend of hers. They worked at the Mall of America in Bloomington [a suburb of Minneapolis, Minnesota]. They got off work at about 7 p.m., and they went to their car to share a ride home. When they started the car it didn’t seem to be running well, so they let it idle for a while, thinking it was just the cold weather. Then they noticed a bad smell coming from the engine, so they shut off the car and investigated. When they opened the hood, they discovered that a cat had climbed into the engine somehow while they were at work. The cat had gotten caught in a belt or something, and it was dead and mangled. The women found some sticks and poked the pieces of the dead cat loose.

They didn’t want to just leave the cat there on the ground, so they put it in a shopping bag and started walking back towards the mall to throw it in the garbage. But before they got there, a woman ran by and swiped the bag, presumably thinking it was full of Christmas gifts or something. The two women thought that was pretty funny. They decided that they should report the incident to mall security, because next time the thief might steal something of value.

As they were walking to the security office, they noticed a big hullabaloo. They stopped to see what was going on, and they saw that a familiar someone—the dead-cat thief!—had fainted and she was being loaded into an ambulance. Then a bystander saw the shopping bag and told one of the paramedics that it belonged to the sick woman. So a paramedic put the bag on the woman’s chest and secured it with a bungee cord. Of course, nobody had any firm details about what happened next, but my friend thought the thief probably had a pretty rough time of it when she woke up and the dead cat was still there.

I know I have heard or read this story before, but when I pressed my friend for details she kind of bit my head off. She was upset that I didn’t believe the story, so I just dropped it. But it’s been driving me nuts ever since. Was this a

Twilight Zone

episode or something, or was it just one of those stories you collect?

Sent to me in 1993 by Maria Westrup of Indianapolis. Many other readers, including several Midwestern newspaper columnists, confirmed that the old “dead cat” legend had found a new home at the gigantic Mall of America. And why not, since just about every other mall and department store in the United States, plus some abroad, have had the same story told about them? I’ve traced the version in which the cat-package is accidentally switched with one containing food—steaks, a ham, or the like—back to 1906, and both versions continue to pop up. It’s an especially popular legend during the Christmas shopping season. Often the victims observe the thief faint twice, once when she feels into the bag to check on her loot, and again when she returns to consciousness while on the paramedics’ stretcher and sees the dead cat staring her in the face. Ann Landers published a version in a letter signed “The Okie,” in 1987, and she merely thanked her reader for “letting the cat out of the bag,” evidently willing to believe the tale. An English music hall song, “The Body in the Bag,” retells the legend, and this musical treatment has passed into folk-song tradition. Yevgeny Yevtushenko included a Russian version, in which the cat-package is switched on a commuter train, in his 1981 novel,

Wild Berries.

That dead cat really gets around, and the thief always gets what he or she deserves.

“The Runaway Grandmother”

O

ne of the worst (or best) horror travel stories I’ve heard is of the American family traveling by Volkswagen through Spain. The two children were in the back seat of the car with Grandmother when she died. The parents decided to phone the American Embassy for advice, but first had to find a phone.

The children became hysterical with Grandmother still in the back seat, and there was no room in the front of the Volkswagen for all four of them. So the father wrapped the grandmother in a blanket and put her in the luggage rack on top of the car. (In emergencies you do what you have to do.)

They came to a filling station and all piled out of the car to make the phone call, leaving the keys in the car. They returned to find the car had been stolen, along with Grandmother and their luggage and passports. They never did find any of their possessions.

From a letter to the travel editor of the

Washington Post,

December 23, 1990, from Wilfred “Mac” McCarty. Another letter published in that column on May 26, 1991, described a family from Frankfurt, Germany, who also lose their dead grandmother on a car trip in Spain. When Americans repeated this story, they were told that “this is a scenario that is commonly presented to first-year law students in Germany with instructions to determine and list all possible infractions of local and international law.” Using families of different nationalities traveling in various foreign countries, “The Runaway Grandmother” is popular all over Europe, particularly in Scandinavia and Great Britain; it has migrated to Australia as well as to the United States. In American versions the family is motoring either in Mexico or Canada; in the latter setting, the grandmother’s body is put either into a canoe on the car’s roof or into a boat towed behind the car. Although the stolen corpse is the functional equivalent of the dead cat in the preceding legend, the grandmother story seems to have originated in Europe during World War II, whereas the cat story is older and of American origin. Elements of this widespread legend are echoed in sources ranging from John Steinbeck’s

The Grapes of Wrath

to the film

National Lampoon’s Vacation.

Novelist Anthony Burgess justified using this story in a 1986 book

—The Piano Players—

by making the unlikely claim that he had invented it in the 1930s. Whatever its source, “The Runaway Grandmother” legend offers an apt metaphor for the uneasiness modern people feel about aging and particularly death. Like a mortician in real life, the grannynapper takes the problem off the hands of the living.

“The $50 Porsche”

T

he men in the insurance office propped their feet on the desks, puffed cigars and perused the classified ads. It was a Monday morning ritual. They were all talking about the eye-stopper.

Mercedes 280 SL For Sale. Sun Roof. Loaded. Burgundy, Leather Interior, Stereo. $75.

Their mouths watered. But their eyes moved on down the column. It had to be a misprint. No one, but no one, would sell that car for $75.

Finally, the talk turned to other things, and the car gradually was forgotten.

One salesman didn’t forget it though. He kept looking at the ad, and finally he dialed the phone number listed.

A woman answered.

“I’m calling to inquire about the Mercedes,” he said. “Is it still for sale?”

“Oh yes,” she said. “It’s still for sale.”

“And the price is $75?”

“That’s right—$75.”

“Well, I’d like to come out and look at it.”

He drove out to the address given him. It was a large, split-level brick home with a swimming pool and tennis courts. The manicured shrubbery and lawns bespoke the presence of a gardener.

An attractive blonde woman answered the door.

“I’ve come to see the Mercedes,” he said.

She waved her hand at the double-car garage. “It’s out there. Here’s the keys. Just lift the door and crank it up.”

The sight of that car took his breath away.

He could see his reflection in the hood. Its wheel covers gleamed. The interior was all plushy, shiny, tan leather and dark wooden paneling.

He tried the sunroof. He tried the stereo. Everything worked.

The engine ran like a dream. The car was perfect.

He went back to the door.

“The price is still $75?” he asked one more time.

“Yes, it is,” the blonde said firmly.

His hand was shaking as he wrote the check.

But he couldn’t leave without asking. “Lady, I just want to know why you’re selling this car for $75. Nobody would sell that car for that.”

She hesitated just a moment, but then she smiled just a little.

“I’ll tell you,” she said. “About five years ago, I met and married the perfect man. He was tall, well-built and good-looking. He was an engineer. He brought home about $200,000 a year and that’s how we could afford this house and all you see here. Our marriage went well. Everything seemed fine.

“There was just one flaw. One of our neighbors was a beautiful, sexy woman. And last week, the two of them ran off together.”

She paused and smiled again.

“He called me this week.

“‘Now don’t hang up, Honey, just don’t hang up,’ he said. ‘You’ve been a good sport, and I know you’re going to be a good sport about this, too. I know I did you wrong. You deserve better, and I’m sorry. But I just want you to do me a favor: Sell the Mercedes and send me half the money.’”

This beautifully elaborated version of a classic automobile revenge legend was written by Roger Ann Jones, managing editor of the

Columbus (Georgia) Enquirer

for the October 10, 1983, edition. Ann Landers published a reader’s version in a 1979 column, commenting “truth is stranger than fiction.” When she reran that column in 1990 both she and I were inundated with letters from readers who recognized a legend they had heard. So Landers then published a comment from a reader who remembered back when the story featured a $20 Packard. My own files contain mostly $50 Porsches, but also prices running from a mere $10 up to $500 and cars including Cadillacs, BMWs, Karman Ghias, and Volvos. Often the husband has run off with his secretary. In England, the story has been documented back to the late 1940s; prices range from 5 to 50 pounds sterling for either a Rolls Royce or a Jaguar. Sometimes the terms of the Englishman’s will specify that his widow sell the car and give the proceeds to his mistress. I heard singer John McCutcheon perform his own variation on

A Prairie Home Companion;

it began:

One morning while reading the paper,

In search of a new set of wheels,

The classifieds had a most curious ad,

In their listing of automobiles.

What seemed like a wild stroke of luck:

“Corvette Stingray,” it said,

“Low mileage—bright red,

83 model: 65 bucks.”

“Dial R-E-V-E-N-G-E”

A

t the sound of the beep: A Dallas wife did this two weeks ago, but it shows Houston kind of genius. Learning her husband was on a three-week stay in the Caribbean with another woman instead of in London on business as he had said, the Mrs. quietly packed up her things, retrieved a number from directory assistance, dialed it and then left the line open for the Mr. to find when his trip was over. The number? That of the Hong Kong continual time and weather recording….

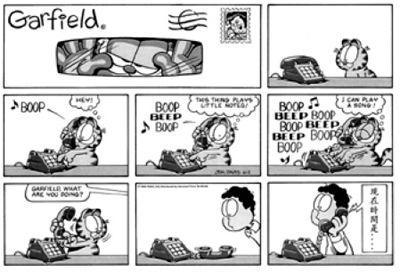

Garfield

© Paws, Inc. Reprinted with permission of Universal Press Syndicate. All rights reserved.

O

ne woman was visiting her out-of-town boyfriend, only to be abandoned as he supposedly went to visit his mother in the hospital. But when it was revealed that the mother was in perfect health and Mr. Two-Timing Rat actually was on a romantic rendezvous, this woman’s solution was to call time and temperature in Tokyo, then leave the phone off the hook.

Version one was published in the

Houston Post

some time in 1990; version two was in a

Chicago Tribune

article by Marla Donato headlined “Nifty ways to leave your lover,” and published as a Valentine’s Day item on February 12, 1993. I’ve collected references to this ploy—usually used to get rid of an unwanted live-in lover—going back to 1982. Foreign versions, such as a comical poem based on the legend published in the English journal

New Statesman

in 1986, usually mention calling the New York City number for the “speaking clock.” The legend became the basis of a “Garfield” cartoon on Sunday June 2, 1996. Telephone company experts assure me that the trick would not work, since calls to the time and temperature service have an automatic cutoff after a specified period, usually one minute.