To Kingdom Come (14 page)

Authors: Robert J. Mrazek

The sky around the combat boxes was soon so crowded with enemy machines that there were too many for the gunners to count. Still outside machine-gun range, about forty Fw 190s formed up in a circular formation before peeling off in elements of four. Flying at nearly 400 miles an hour, they were quickly reduced to black specks in the distance.

Ted braced himself for what he knew was coming, warning all the gunners in

Patricia

to be ready. Their squadron of six Fortresses was in coffin corner, the low squadron of the low group in the first combat box in the formation. Al Kramer, who was leading the low squadron in

Lone Wolf,

ordered them all to tighten up.

As even more fighter groups continued to arrive, German air controllers began to divide their forces among the bomber groups following behind the lead formation. Eight miles back in the bomber stream, Bf 110s with air-to-air rockets mounted under their wings appeared on the flanks of the 306th group and began launching rockets at the bombers on the outer flanks of the combat box.

After the rockets were fired, a staffel of ME-109s made an attack on the 306th’s high squadron from out of the sun. Andy Andrews saw them coming and called out their position on the intercom.

Three of the fighters headed straight for

Est Nulla Via Invia Virtuti.

Rolling onto their backs, they flashed past in a blur of tracer bullets and cannon fire. Andy felt a shudder in the controls. Checking his instruments, he saw that the oil pressure in the left inboard engine was dropping fast. One of the cannon rounds had severed the engine’s oil line.

When the oil pressure dropped to zero, he was forced to cut power to the engine and feather the propeller to prevent it from spinning out of control. Without lubrication, the spinning propeller would have built up enough heat to melt its metal housing.

He had a critical decision to make. With only three engines, it wasn’t possible for

Est Nulla Via Invia Virtuti

to keep up with the rest of the 306th. Andy asked Keith Rich, his copilot, for their fuel situation. It would be tight, Rich told him, but Stuttgart still lay within their range. They were less than thirty minutes from the target.

Andy could also turn the plane around and head straight back for England, but that seemed like quitting. There was another factor, too. He had faced a similar crisis three weeks earlier on their mission to Gelsenkirchen. On that one, they had just crossed the German border when the superchargers had frozen up on both of the right-side engines.

To stay in the air, it had been necessary for him to keep the wing with the two good engines canted down low to prevent the plane from going into a flat spin. As they headed back across France, he was flying lopsided.

A formation of several dozen fighters approached them, and he saw that they had inline engines. Spitfires and ME-109s had inline engines. He hoped they were Spitfires.

They weren’t. The planes were ME-109s flying to intercept the rest of the bomber stream. A dozen of them made passes at

Est Nulla Via Invia Virtuti

as they flew past. Three came back to play with them, and it soon seemed as if everything was going to pieces in the plane. All the guns on the bomber were blasting away while Andy tried to keep the plane straight up so they would have a good field of fire. Almost miraculously, the cavalry had come to the rescue in the form of a squadron of P-47s, but the memory of the ordeal was fresh in his mind.

He knew there was a measure of safety inside the massive bomber stream. Within it, their Fortress was just one more schooling fish. Alone as a cripple in broad daylight, they would offer German fighter pilots a tempting opportunity to rack up a four-engine bomber kill. Since

Est Nulla Via Invia Virtuti

was in the high squadron of the lead group, he could afford to slowly drop back inside the stream without ending up easy prey.

Andy made his decision. He told Keith Rich that as soon as they dropped their bombs on the factories at Stuttgart, he would dive for the deck and head back at treetop level across Germany, France, and finally the English Channel to their base at Thurleigh.

As

Est Nulla Via Invia Virtuti

began slowly falling back in the formation, one of the pilots in the element behind them moved up to take over his position as the element leader.

He gave Andy an encouraging thumbs-up as the Fortress surged past.

The Blind Leading the Blind

Stuttgart, Germany

388th Bomb Group

Patricia

Second Lieutenant Ted Wilken

0930

O

ne moment they were tiny black smudges in the distance, maybe dirt specks on the cockpit windshield. A few seconds later, they were four Fw 190s coming toward them at 400 miles an hour. later, they were four Fw 190s coming toward them at 400 miles

For Ted Wilken, the hardest thing about being a B-17 pilot was not being able to personally shoot back. He could only fly stolidly along in the bomber train, keeping

Patricia

slotted into its position in the combat box, while trying to provide his machine gunners with good fields of fire.

The first wave of German fighters headed straight for the low squadron.

In an astonishing acrobatic display, the Fw 190s simultaneously rolled over onto their backs and opened fire at a hundred yards. If the beautifully calibrated maneuver hadn’t been so lethal, the sheer artistry of it would have been breathtaking.

The top turret gunner opened fire on one of them with his twin .50s, and Carl Johnson, the bombardier in the nose compartment, cut loose with his single .30-caliber peashooter.

In the cockpit, it began to smell like the Fourth of July. The muzzles of the top turret guns were less than three feet above Ted’s head, and he could feel their reassuring vibration through his gloved hands on the steering column.

Seconds later the fighters were gone, diving beneath the bombers before peeling off to the right and left in preparation for another attack. Out ahead of the formation, another wave of fighters materialized behind the first one.

The attacks on the low squadron quickly struck home. Lieutenant James Roe, the pilot of

Silver Dollar

, was flying directly behind and beneath Ted in the second element as the fighters continued diving at them. A 20-millimeter cannon round slammed into the nose of

Silver Dollar

, killing the bombardier, Manley Frankenberg, and wrecking many of the cockpit controls.

Before the plane tipped over into a flat spin, Roe ordered the rest of his crew to bail out. Parachutes blossomed around the fuselage as it fell away. One of the enemy fighters continued to follow the Fortress down, firing short bursts into it as if to hurry it along. The pilots in the combat box behind the 388th watched it go.

Sky Shy

, piloted by Lieutenant Myron “Mike” Bowen, was flying alongside

Silver Dollar

in the second element of the low squadron when a fighter attacking from the left side raked it from fore to aft, wounding both waist gunners and blowing the head off the top turret gunner. In a simultaneous frontal attack, a second fighter knocked out one of Bowen’s engines. Determined to keep going, Bowen increased the manifold pressure in the three remaining ones to try to keep up.

While the initial attacks were concentrated on the low squadron, the lead and high squadrons of the 388th faced their share, too, with the fighters coming in frontally and from both sides. Lou Krueger was piloting

Passionate Witch II

in the first element of the high squadron when a cannon round shattered the cockpit, instantly killing him and seriously wounding his copilot, Johnny Mayfield, who fought to retain consciousness as the attacks continued.

A few of the German fighter pilots were recklessly brave, waiting until they were no more than fifty yards from the bombers before opening fire. This daring maneuver gave them a better chance of delivering a mortal blow, but a deadly collision was no more than a heartbeat away.

Watching them come in, the Greek was reminded of how the fighters’ tracer rounds always looked to him like landing lights. But these pilots weren’t landing. They were trying to kill him. As one of them rolled and fired at

Slightly Dangerous II

, Sergeant Arthur Gay, the Greek’s top turret gunner, unleashed a short burst from his twin .50s.

The ME-109 disintegrated in front of their eyes. A fraction of a second later, bits and pieces of the plane’s fuselage, engine, and pilot sped past the side windows of their cockpit.

For another five minutes, the fighters darted through the 388th’s formation with almost maniacal ferocity. Major Ralph Jarrendt, the lead pilot of the 388th in

Gremlin Gus II

, estimated that the group absorbed at least twenty separate attacks in the first minutes of the battle.

And just as suddenly, it was over.

The reason for the fighters’ abrupt departure quickly became obvious when the first barrage of black greasy explosions materialized above the solid cloud layer and erupted around them. Even if the Americans couldn’t see Stuttgart, the hundreds of antiaircraft batteries surrounding the city obviously knew they were there.

Stuttgart, Germany

388th Bomb Group

Gremlin Gus II

First Lieutenant Henry W. Dick

0942

From his small cushioned chair bolted to the deck of the nose compartment in

Gremlin Gus II

, Henry Dick, the lead bombardier of the 388th, pressed his right eye to the hard rubber eyepiece on his Norden bombsight and tried to find the ball-bearing factories they had come to destroy.

The superbly engineered bombsight had three primary components, including an analog computer, a small telescope, and the electric motor that adjusted the gyros after it had locked onto the target. Once the target was acquired, the bombsight would engage, and then automatically adjust itself as the aircraft headed toward the bomb release point.

Before the Norden bombsight could generate a good target solution, however, it was necessary for Henry Dick to visually locate the target using the bombsight’s telescope. He then needed to input the approximate distance to the target as well as the plane’s ground speed and altitude into the computer.

He had already made an estimate of ground speed based on a combination of wind drift and the plane’s airspeed. Now he had to visually find the target in order to estimate the distance they were from it.

The difficulty of the current problem was compounded by the intensity of the flak barrage they were now flying through. It was as heavy as he had ever seen, and the plane was being buffeted wildly in the turbulent air as cannon shells exploded above, below, and around them.

When

Gremlin Gus II

reached the initial point of the bomb run, Major Jarrendt turned over control of the plane to Lieutenant Dick. Theoretically, the bombsight should now have been flying the airplane, automatically correcting its course until the target was reached, when it would automatically toggle the Fortress’s payload of ten five-hundred-pound bombs.

The rest of the bombardiers in the group were watching and waiting for Lieutenant Dick to open his bomb bay doors and release his payload. That would be the signal for them to drop their share of high explosives on the ball-bearing factories.

Henry Dick was very good at his job, but his current predicament was unprecedented, at least in his experience. As hard as he tried, he was unable to make out any of the identifying features he had been briefed to look for. The stratus clouds were impenetrable. If Stuttgart was down there, he had no way to confirm it.

Up ahead of them, the 96th Bomb Group suddenly turned left off the formation’s original flight path. Unable to make his own independent observation, Henry Dick assumed the lead bombardier of the 96th had a good target solution, and swung

Gremlin Gus II

to the left to follow them. The rest of the 388th trailed behind.

As he continued to stare through the eyepiece of the bombsight, the cloud cover briefly thinned out, and Henry Dick thought he could make out one of the checkpoints he was looking for. Through the thick, creamy haze, there was no way to be sure, but he believed they were now on the right course.

A few moments later, the lead planes of the 96th made a turn to the right. Confident that he was now headed in the right direction to reach the target, Henry Dick continued to steer the lead plane of the 388th on their original course.

The five bomb groups coming behind them, the 94th, the 385th, the 95th, the 100th, and the 390th, all fell into line behind the 388th. As the formations began to diverge, the umbrella barrage intensified, and 88-millimeter cannon rounds began to find their mark.

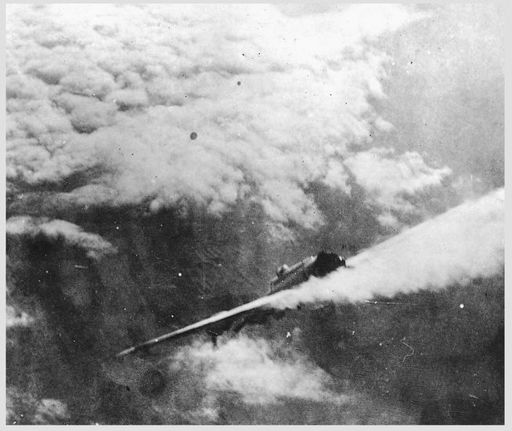

Wolf Pack

, flown by Lieutenant Eddy Wick, had already lost one engine, and he was trying to keep up on the remaining three when a flak burst exploded beneath them, knocking out a second engine. Out of control, the plane began flying straight up in the air for several agonizing moments before falling away.