To Kingdom Come (9 page)

Authors: Robert J. Mrazek

Almost insane with worry, Braxton decided she had to act. Scouring her meager wardrobe, she put on a gray dress and walked to the base home of the colonel in charge of the training command.

“I have to talk to you, sir,” she said when he came to the door. “Ted Wilken is not a cheat. He is the most honorable man I’ve ever known, and you can’t let his life be ruined.”

The words were flooding out before she suddenly remembered that under air force regulations, they weren’t even supposed to be married. It was too late now. At one point during her desperate plea, he had to turn away, and she saw that he was smiling.

“I’ll think about it,” he told her finally.

“That is all I can ask,” she said, before adding, “If it ever gets back to Ted that you talked to me, you won’t live to see another day.”

He burst out laughing.

“This is between you and me,” she pressed on. “Swear?”

He nodded.

Ted was required to take the course all over again. The cadet who had copied his work was expelled from the program.

They had moved on to Nashville for heavy bomber training when Braxton realized she was pregnant. Ted was overjoyed. He would probably be overseas when the baby arrived, but would be awaiting word.

Shortly before Christmas, the couple received a harsh note from Ted’s mother expressing her disappointment at their lack of responsibility in saving money for the future. She had lavished a large cash wedding gift on them, and Ted was spending it in ways that she didn’t support, including lending money to other young married couples who were in training with them, and living on a shoestring.

Braxton wrote back on behalf of both of them.

Dear Helen,

Teddy will probably be on combat in July. We have enough love and faith in each other to get through this. I utterly refuse to become a moaning war bride. It’s going to be hard on all of us who adore and worship Teddy to have to sit and wait at home.

I haven’t felt too badly—no early morning sickness (I just get sick in the morning and stay sick ’til evening). I know every inch of the bathroom quite intimately. Seems to me I can vaguely remember liking food....

As for our financial discussion, I’m sorry if we appeared uppity when you advised us to save. I really believe that Teddy must take his own responsibilities now. We don’t resent advice—please believe that. It’s just that we feel

now

is the all important time in our lives. In the Air Corps you learn to live from day to day. To you that may seem a pointless philosophy. But to us who may never know a tomorrow, it is the only way to find peace and contentment. Money, now, is the most unimportant thing in our lives. You see, there is always the chance that this may be all the married life Ted and I will ever know—all there ever will be.

Don’t you see, this

is

our rainy day. The wettest, stormiest, most hellish rainy day Teddy and I will ever know. I’m not writing this in a morbid or complaining way—I have thanked God every day for the privilege of being with him. I just wanted you to know how and why we reason like we do. It’s just trying to live a lifetime in a little while. I guess war has made us a very hardened and practical lot. We saw that when Mil Stevens was killed at George Field. You learn to be thrifty with your emotions. Teddy has a dangerous job to do and it must not be cluttered with emotions. That’s the hardest thing all of us Air Corps families have had to learn—to accept—not to question.

When Teddy goes on combat, I want him to remember how much we love him so he will have twice the incentive that anyone else has to be courageous and do his job uncomplainingly and with honor. It’s an awful easy thing to die, but sometimes to live and do it gracefully is the seemingly impossible thing.

I tell you all this because I don’t want you to think we are unfeeling or unthinking or extravagant for no reason. We have weighed the odds carefully and know just where we stand. Our morale is our wealth and happiness. We are trying the only way we know how.... We love and miss you terribly. Always, Betsy

In February 1943, Ted was on his way by train to Spokane, Washington, to be assigned his crew, when he got into trouble again. At one of the stops, he was taken into custody by military police after going to the Western Union office and sending Betsy a telegram telling her how much he missed her.

He had veiled the words in pig Latin, a jargon that was then the rage among the pilots, in which the beginning consonant of each word was transposed to the end. At the next stop, he was taken off the train and interrogated as a possible enemy spy. The telegraph operator had alerted the military police after reporting that he had used “a secret code.” It took him several hours to convince the police it was harmless.

At Spokane, Ted was assigned a crew and they began training together. He began using the same principles he had employed as the captain of his championship teams to mold his flight crew into a solid fighting unit. Although air force regulations prohibited fraternization between officers and enlisted ranks, Ted quickly broke the boundaries.

Every Friday night, he would rent a hotel suite in Spokane for the crew to get together informally and play poker over drinks and dinner. If they were going to be fighting together, he told them, they might as well enjoy being together as friends whenever they had the opportunity. Once inside the suite, it was all on a first-name basis.

Ted also made sure every member of the crew had his personal affairs in order. He didn’t want them to leave for England with any serious worries. Some of them needed money for their families. He lent it to them. Whatever the problem, he was there with advice and support. All for one. One for all.

Ted and Braxton spent his final fifteen-day embarkation leave together in Bronxville. The days went by in a blur, and then he was gone. She settled in for the long wait before he came back.

In England, Ted’s crew was assigned a new Fortress. Together, they decided to name it

Battlin Betsy

. Ted wrote her that he thought he had the best-trained and most confident crew in the squadron. His copilot, Warren Laws, was very good in the air, calm and competent, and deserved his own ship. The rest of the men not only knew their jobs but could count on one another, no matter how tough things got. His training methods might have been unorthodox, but he thought they had worked out well.

On August 3, Braxton gave birth to their baby, Katherine Ann. They had already agreed on the name if it was a girl. Less than a week later, a letter was delivered to Ted at Knettishall. Included with it was a photograph of Braxton and their new daughter.

Dressing in the darkness of his Quonset hut for the Stuttgart mission, Ted put the photograph in the breast pocket of his flight suit over his heart. It would be his sixth mission.

Jimmy

Monday, 6 September 1943

384th Bomb Group

Grafton Underwood, England

Second Lieutenant James “Jimmy” Armstrong

0300

“

L

ieutenant Armstrong?” came the disembodied voice behind the flashlight beam. “Briefing in half an hour.”

The big man slowly hauled himself out of the narrow bunk. His copilot slept in the bed on one side of him, his navigator on the other. He made sure they were awake, too. Still groggy, he had to remind himself of which men remained from the original crew he had been assigned back at Gowen Field in Boise, Idaho.

His flight crew’s confidence was at low ebb, and he wasn’t sure what more he could do to bolster their spirits. Morale in the rest of the 384th Bomb Group wasn’t much better.

Recent losses had cast a pall over the whole base. The group had lost ten Fortresses in June, and another twelve in July. Jimmy wasn’t worried for himself. There was no doubt in his mind that he was going to make it through, but it was hard to maintain crew cohesion with so many men coming and going.

At times it seemed like his own constantly rotating crew was being sent by the League of Nations. Wilbert Yee, his new bombardier, was Chinese. James H. Redwing, the ball turret gunner, was a Hindu whose family came from India. He spoke English like some professor at Oxford.

Jimmy’s former copilot, Luke Blanche, was a full-blooded Cherokee from Broken Toe, Oklahoma. The machine gunners included Presciliano Herrera, a Mexican kid, and William Deibert, whose family was German. Sid Grinstein, his original flight engineer and top turret gunner, was Jewish.

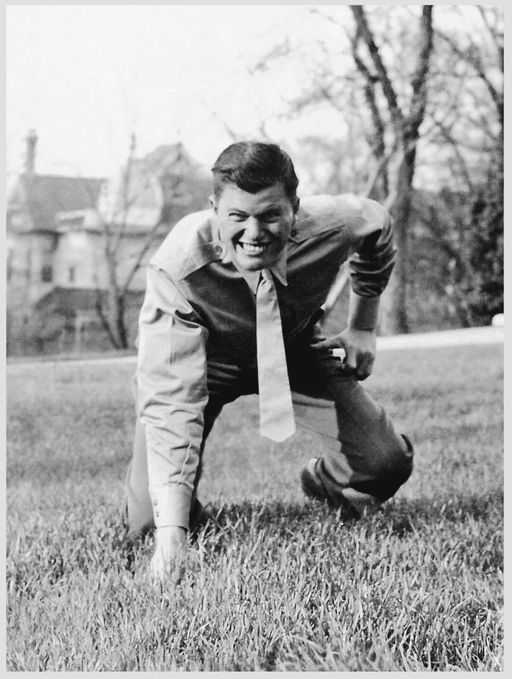

After ten missions, Jimmy had reluctantly concluded that combat leaders in the air force were made, not born. He had come a long way in a short time from the athletic fields at Georgia Tech.

He was finishing the first semester of his sophomore year when he returned to his dorm room one Sunday afternoon and learned that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. Like his roommates, he was ready to fight. When he signed up for the air corps, the fun-loving giant was also looking for adventure. Ten months later, he was awarded his wings.

Jimmy was just nineteen years old. Someone told him that he was probably the youngest pilot in the whole air force. His next assignment as a newly minted B-17 pilot was at Hendricks Field in Sebring, Florida.

To celebrate winning his wings, he flew a Fortress to his hometown of Bradenton, Florida, where he dove down to an altitude of fifty feet before thundering over his parents’ home at two hundred miles an hour, clipping the tops off the Australian pine trees that surrounded the property. The terrified officer flying with him in the copilot seat thought they had blown the roof off the house.

He came from a clan of warriors. The first Armstrongs in the colonies had arrived from Scotland in the mid-1700s. Two of his ancestors had fought against the British in the American Revolution. During the Civil War, both his great-grandfather and his grandfather rode with Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade. His father had battled German U-boats in the North Atlantic in the last war. After Pearl Harbor, his father had reenlisted to fight the Japanese.

In spite of his commanding physical presence, his tender age led to many awkward moments. As he tried to explain to his crew, all of whom were much older, he was not only big, but he was “rough cut.”

The crew had begun flying combat missions in a B-17 named

Sad Sack II

. The figure of Sad Sack, a cartoon character in

Yank

, the army newspaper, had been painted on the plane’s nose.

Things began to unravel for them on their fifth mission, which was the August 12 attack on Gelsenkirchen, Germany, in the Ruhr Valley. In the preflight briefing, the flight crews had been told they would attack the target at an altitude of thirty-one thousand feet, which was far above the range of the German 88-millimeter cannons.

The briefer was wrong.

Of the seventeen planes in the 384th that reached the target, five were shot down by 88s. To complicate matters, the air temperature at thirty-one thousand feet was 55 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. Presciliano Herrera, the left waist gunner, had come back with frostbitten hands and was no longer able to fly.

On August 16, John Heald, Jimmy’s original bombardier, and Sid Grinstein, his flight engineer, were ordered to join another crew as last-minute substitutes on a mission to Paris. The 384th Bomb Group lost only one plane that day, but Heald and Grinstein had gone down in it.

One day later, Jimmy had flown the Schweinfurt mission.

Sad Sack II

was about a hundred miles into Belgium when the German fighters began coming up from the airfields along their route to intercept them. The attacks were the most intense he had ever encountered.

Another pilot in the 384th had once claimed to Jimmy that whenever he saw enemy fighters coming, he gave out with a Sioux war whoop on the intercom to inspire his crew. He had died with his crew over Germany back in July. Jimmy didn’t believe in war cries. He just hoped his gunners shot well.

As

Sad Sack II

approached Schweinfurt, the bomber directly above them in the formation was hit by cannon fire, and its right wing burst into flames. Jimmy’s waist gunners began screaming frantically on the intercom that the stricken Fortress was descending straight toward them. Jimmy managed to avoid the other plane, now engulfed in a ball of fire, as it plummeted past them in its death spiral.

After Wilbert Yee, his new bombardier, dropped their bombs through the flak cloud over Schweinfurt, the attacks intensified again. When a Focke-Wulf 190 suddenly came at them head-on, Jimmy lifted his right wing when he saw the first flashes of the fighter’s guns. It didn’t help. A moment later, machine-gun bullets began smashing into the cockpit. One of them sliced through his copilot’s sheepskin-lined flight jacket and splintered the armor plate behind his seat. Amazingly, he was unhurt.

The fighters kept on coming, and his gunners kept firing back until they ran out of ammunition. In the next head-on attack, a 20-millimeter cannon shell set fire to his left inboard engine and sprayed the nose section with shrapnel, wounding Yee and Carlin, the navigator. When that engine caught fire, Jimmy feathered it to keep it from running out of control. As they finally approached the French coast, the attacks tailed off. Jimmy brought the Fortress home on three engines.