To Hell on a Fast Horse (8 page)

Read To Hell on a Fast Horse Online

Authors: Mark Lee Gardner

For years, the mercantile firm of L. G. Murphy & Co. and its successor, J. J. Dolan & Co., commonly known as “The House,” had the upper hand in just about every moneymaking venture in the region. It operated for a time as the post trader at Fort Stanton and received numerous government contracts for beef, corn, flour, and other provisions. In Lincoln, The House maintained a brewery, saloon, and restaurant, as well as a large store. It also performed, on a limited basis, the services of a bank. Yet The House’s unashamed greed (even

though many of its business practices were not unusual for the time), its long reach into local government, and its connection to territorial power brokers in New Mexico’s capital—the infamous “Santa Fe Ring”—earned it considerable ill will among the locals.

“Only those who have experienced it can realize the extent to which Murphy & Co. dominated the country and controlled its people, economy, and politics,” remembered one county resident. “All Lincoln County was cowed and intimidated by them. To oppose them was to court disaster.” Three men—John Henry Tunstall, Alexander A. McSween, and John S. Chisum—did oppose The House’s regional supremacy, and it cost two of them their lives.

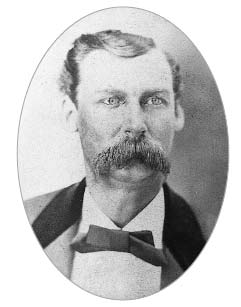

A twenty-four-year-old Englishman with plenty of gumption—and capital to go with it—John Henry Tunstall first arrived in Lincoln

County in November 1876, determined to carve out his own modest empire from its vast lands. He was also a sure enough dude, complete with tailored suits (he had a penchant for Harris tweed), riding out-fits, and top boots. His hair was sandy colored and wavy, though well groomed, and he sported chin whiskers and a pencil-thin mustache. In photographs, he appears as stiff and aristocratic as the man on the Prince Albert tobacco tins, but those close to the young Englishman thought he was good-looking and personable. He was a prolific letter writer, expounding at length to his father in England (his chief financial backer) on the Wild West and predicting that he would make a fortune there. His plans could just as easily have been written by a member of The House: “I propose to confine my operations to Lincoln County, but I intend to handle it in such a way as to get the half of every dollar that is made in the county by anyone, and with our means we could get things into that shape in three years, if we only used two thirds of our capital in the undertaking.”

John Henry Tunstall.

Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico

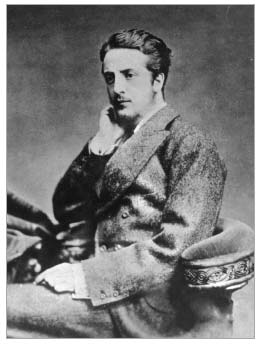

Tunstall had focused his sights on southeastern New Mexico because of a chance meeting with Lincoln attorney Alexander A. McSween at a Santa Fe hotel. McSween, a Scotsman ten years Tunstall’s senior, was new to the Territory as well, having arrived with his wife, Susan, in March 1875. With a drooping mustache as thick as his Scottish brogue, McSween had initially worked as a lawyer for The House, where he got an insider’s look into the firm’s many business dealings. Within a few months, McSween had used this privileged information to help Tunstall buy a cattle ranch and open a mercantile store in Lincoln. The pair also established a bank; cattleman John S. Chisum served as the bank’s president. Chisum had his own grievances against The House, whose loose policy when buying beef for its government contracts had served as an open invitation for rustlers to steal from Chisum’s herds on the Pecos.

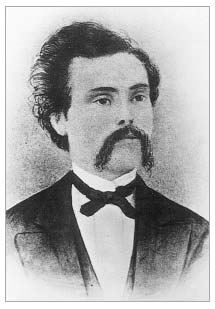

The carefully plotted competition from Tunstall and McSween came at a time when The House was financially on its knees (the prin

cipals were not the best businessmen). And the fact that Tunstall was an upper-class English Protestant, while The House hothead, Jimmy Dolan, and his partner, John Riley, were both Irish Catholic, made this even worse. Born in County Galway, Ireland, in 1848, Dolan had emigrated to the United States at age six. During the Civil War, he had been a drummer boy for one of the colorful Zouave regiments from New York State, and it was as a U.S. infantryman that he had come to Lincoln County. He was short, just five feet, two and one-half inches tall, and his temper was even shorter.

Alexander McSween.

Robert G. McCubbin Collection

Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico

James “Jimmy” Dolan.

Robert G. McCubbin Collection

Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico

By early February 1878, both sides had spread vicious rumors about the other; both had attacked each other publicly in the territorial press; and both had spewed out a few choice personal threats. Both had also put men on their payrolls who knew the inner workings of a Colt six-shooter and a Winchester repeater. The House, what with its cozy relationship with the district court, had orchestrated criminal

charges (embezzlement) and a civil suit against McSween. But Dolan’s legal shenanigans achieved their finest moment on February 7, when he secured a writ of attachment against McSween. Dolan turned the writ over to Sheriff William Brady, another House tool, who happily attached any and all property of both McSween

and

Tunstall: store, lands, cattle, horses—even such personal items as portraits of Tunstall’s parents.

The first blood spilled in the Lincoln County War came just eleven days later at approximately 5:30

P.M

. Tunstall and four of his men, including the Kid, were on their way to Lincoln with a small herd of horses. Tunstall’s party, strung out over a distance of a few hundred yards, had just crested a divide and was descending through the rugged hills above the Ruidoso Valley when they flushed a flock of wild turkeys. Two of Tunstall’s men started after the dusky birds; moments later, shots rang out on their back trail. Billy and John Middleton, who had been bringing up the rear, came forward at a gallop. Behind them, riding hard, was a party of nearly twenty mounted men, members of a posse sent to gather up Tunstall’s horses, except it was obvious that this posse was bent on more than simply attaching livestock. Middleton raced toward Tunstall, who had remained near the horse herd, and shouted at him to flee. Agitated and confused by the gunfire and commotion, Tunstall did nothing.

“For God’s sake, follow me,” Middleton pleaded before spurring his horse on.

“What, John? What, John?” was all the surprised Tunstall managed to speak.

At the first sight of the posse, the turkey chasers, Dick Brewer and Robert Widenmann, had retreated to a nearby hillside, where they planned to make a stand behind some large boulders and trees. Middleton and the Kid were close behind them. Their pursuers pulled up when they saw Tunstall by himself.

The first members of the posse who approached Tunstall were

William “Buck” Morton, who was Jimmy Dolan’s stock foreman, and Tom Hill. Hill was one of The Boys who had been imprisoned with Jesse Evans in the Lincoln County jail (Evans was also a member of this posse—The Boys were Dolan men, bought and paid for). Tunstall froze when he recognized Morton and Hill, but Hill said he would not be hurt if he gave himself up. Tunstall urged his horse toward the two men. When the Englishman got close, Morton put a rifle bullet through his chest. Tunstall tumbled out of his saddle. Hill then leapt off his mount and ran up to the dying man and fired a pistol into the back of Tunstall’s head. Billy and the others on the hillside heard the shots, but they could not see what had just transpired. With a stunned voice, Middleton said that Tunstall must have been killed.

In a bizarre act, the posse members carefully arranged Tunstall’s body, placing one blanket beneath it and another over it. The dead man’s overcoat was placed under his bloody head. Tunstall’s horse, which had also been killed, was lying next to its owner. Someone in the posse lifted the horse’s head and shoved Tunstall’s hat under it. The posse did not bother with Billy and the others. Instead, they gathered the stock they were after and rode away. Tunstall’s men waited until it was good and dark and then headed to Lincoln. They would see to Tunstall’s remains later. Billy and Widenmann arrived in the county seat between ten and eleven that evening. Despite the tensions building in Lincoln for some time, the news they brought startled the town. The posse members would later claim that Tunstall had fired upon them first, but as far as the Kid and the others in the McSween camp were concerned—as well as nearly everyone else in Lincoln—Tunstall’s death was nothing short of cold-blooded murder.

Tunstall’s body arrived in the county seat the following day. Because the corpse had been strapped to the back of a horse for part of its final journey, the Englishman’s fine clothes were torn, and his face was scratched from going through the brush and scrub oak in the

mountains. Billy stared down at the corpse after it was laid out on a table in McSween’s home.

“I’ll get some of them before I die,” he said, and then he turned away.

Billy had known Tunstall less than three months, but by all accounts, he liked him a great deal. Frank Collinson, a Texas cowpuncher who first met Billy on the Pecos in 1878, remembered years later the few words the Kid spoke about his former employer: “I heard him say that Tunstall was the only man who ever treated him as if he were freeborn and white.”

It was no use going to Sheriff Brady for help—after all, the posse that killed Tunstall was acting under the sheriff’s authority—but McSween was just as good at manipulating the legal system as Dolan. He marched Billy, Brewer, and Middleton over to Justice of the Peace John B. Wilson, and they swore out affidavits naming those in the posse. Warrants were issued for the accused and turned over to Atanacio Martínez, the town constable. Martínez did not especially want to confront Brady and his well-armed men, but some in the McSween crowd threatened to kill him if he did not do his duty. On Wednesday, February 20, Martínez, with “deputies” Frederick Waite (a twenty-four-year-old, part Chickasaw Tunstall man from Indian Territory), and Billy Bonney, walked to the two-story Dolan store in Lincoln to make the arrests. It did not go well. Brady refused to let the constable arrest any members of his posse, and the sheriff showed that he had the firepower advantage and arrested them.

“You little son of a bitch, give me your gun!” Brady growled at the Kid.

“Take it, you old son of a bitch!” Billy said, handing over his weapon.

Both the Kid and Waite were released after thirty hours, but they were still in jail when Tunstall’s funeral took place the following afternoon. If the wind was just right, they may have heard Susan Mc

Sween’s parlor organ, which had been carried outside to the burial place behind Tunstall’s store. And perhaps the two comrades faintly heard the singing of hymns, all the while growing increasingly determined to have their revenge.