To Hell on a Fast Horse (11 page)

Read To Hell on a Fast Horse Online

Authors: Mark Lee Gardner

At about 5:30

P.M

., Susan and her sister and the five children were allowed to flee the house. The Ealys, next door in the Tunstall store, were also allowed to leave safely. Once these noncombatants were out of the way, the shooting picked up again. The heat was intense, and the leaping flames cast a bright light upon the hills overlooking the

town. Forced by the fire into the final room in the house, the northeast kitchen, it was time for bold and decisive action. Alexander McSween was not a fighter, never had been. Now, overcome with a sense of doom and failure as his home burned down around him, he sat, comatose, with his head down. Billy, though, was exactly the opposite, jumping around the room like a caged cat. He shook McSween and ordered him to get up.

“Boys, I have lost my reason,” McSween cried.

“Mack, now we must run for our lives,” the Kid told him, “it is the only chance for our lives!”

McSween listened as his men went over the escape plan. Five of the defenders, including Billy, would burst out of the house first, drawing the fire of Peppin’s men, after which McSween and the rest were to make their dash for safety. Although the flames illuminated the ground a good distance from the home, the first group got a good jump on the sheriff’s posse before being spotted. Billy saw three of Dudley’s soldiers blasting away at him, or so he later claimed. Morris, the unfortunate health seeker, collapsed in front of the Kid, but he was the only casualty in the first group, the remainder making it safely across the Bonito and into the night. Had McSween and the others followed close on the Kid’s heels, they might have had a chance too, but they did not. The Kid’s party, then, only served to alert the sheriff’s men to the breakout.

When McSween and the rest of his followers did abandon the burning house, they were immediately hit by a deadly spray of bullets that kicked up the dirt around them. They headed for shelter in the backyard. They may not have been in danger of burning alive, but they were still trapped. After a tense several minutes, McSween called out that he wished to surrender. Deputy Robert Beckwith and three other men walked out into the open and approached the Scotsman. When Beckwith came within a few steps, McSween suddenly blurted out that he would never surrender. Gunfire erupted on both

sides. Beckwith fell dead and McSween toppled over on top of him, his body pierced by five bullets. Three others in the McSween group, all Hispanos, also fell in the firefight. One, a young Yginio Salazar, was severely wounded and unconscious but Peppin’s men took him for dead. When he came to, Salazar wisely remained motionless until it was safe to drag himself to a friend’s house.

THE KID’S MAD DASH

through the gauntlet of Dolan gunmen had been his greatest feat to date, but with the death of Alexander McSween, the Lincoln County War was all but over. Yet there were still hard times ahead, especially for the war’s veterans. Lincoln County continued to be a violent place, and the bitter feelings between the two factions remained as healthy as ever. For many, the future offered little more than a return to routine, dirt-poor lives of punching cows and scratching out crops, but for those like the Kid, whose names appeared on arrest warrants from the district court, there were very few options. The war had molded Billy, tested him, but it had also reinforced a lifestyle of doing and taking what one pleased, regardless of the law. For Billy, it was but a short step from being a desperate and defiant young man to being a full-fledged desperado.

A

S THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR

raged, Pat Garrett stayed over a hundred miles away at Fort Sumner. Garrett knew some of the Lincoln County warriors from the buffalo range, but he had no history with Dolan, McSween, John Chisum, or any of them. The fight did not involve him, nor was it any of his business. Within a year of the Big Killing, the shrill whistle of a locomotive had been heard at Las Vegas for the first time, and more and more Anglos were flooding into New Mexico. Garrett was part of that change, and he would play a prominent role in even bigger changes to come, yet he respected the old ways of his adopted home, and Fort Sumner’s native New Mexicans respected him. A few did more than just respect him.

The girls of Fort Sumner thought the rawboned former buffalo hunter was quite a romantic devil. Sallie Chisum, the Pecos cattle king’s niece, remembered that Garrett walked “with a certain swinging grace that suggested power and sureness. Despite his crooked mouth and crooked smile, which made his whole face seem crooked, he was

a remarkably handsome man.” Juanita Martínez may have missed his crooked smile, but she certainly noticed his towering height. Juanita was a sparkling young woman, remembered Paulita Maxwell, “who had the charm of gaiety and light-heartedness.” Everyone adored her, and at the frequent Fort Sumner

bailes,

she had a great many admirers. The admirer she fell in love with, though, was Garrett.

Sometime in the fall of 1879, Pat and Juanita exchanged wedding vows. Their wedding was a huge affair, as were all weddings in the small community of Fort Sumner. It was traditional for the

musicos

to play

La Marcha de los Novios

(“The March of the Newlyweds”) after the nuptials. Oddly enough, a favorite melody for this march was “Marching Through Georgia.” If the

musicos

did play this tune, Pat Garrett, a born and raised southerner, must have gritted his teeth as he joined the new Mrs. Garrett in the grand march. As more dances followed, one after the other, the single girls of Fort Sumner, some carefully chaperoned by their mothers, sat around the edge of the long room on benches or chairs, their brightly colored dresses especially selected for this gala evening. When a girl accepted an invitation to dance, her partner would place his hat in her seat, thus holding her place. And when that particular waltz or polka was finished, the gentleman escorted his partner back to her seat and retrieved his hat, and so on throughout the evening.

Among the folks at the Garrett wedding were some young men who, during the last year, had become regular fixtures around Fort Sumner. Garrett knew them because they were customers at his off-and-on saloon and store operations. And their informal leader went by the name of William H. Bonney, although most knew him as the Kid, or Billito. The Kid spent a lot of time gambling—especially three-card monte—and he loved dancing.

Billy was “a lady’s Man,” recalled his friend Frank Coe, “the Mex girls were crazy about him…. He was a fine dancer, could go all their gates [gaits] and was one of them.” The Kid had a favorite dance

tune, and without fail, at some point during the evening, he would tell the fiddlers, “Don’t forget the

gallina

.” By g

allina,

the

musicos

knew he wanted to hear “Turkey in the Straw.” They knew this because even though

gallina

means “hen” or “chicken,” native New Mexicans used

gallina

for the wild turkey. Like Garrett, Billy had mastered New Mexican Spanish.

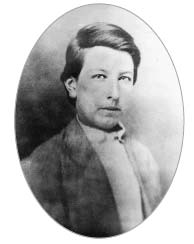

Hanging close to Billy that evening were his pals, and former Regulators, Tom Folliard and Charlie Bowdre. Born in Uvalde County, Texas, in about 1861, Folliard lost both of his parents to smallpox when he was very young, and as a teenager, he stood over six feet and weighed close to two hundred pounds. He had worked for a short time for a Seven Rivers cattleman before stumbling upon the Frank Coe place on the Ruidoso. When Coe decided to try the lad out as a farmhand, Folliard hitched Coe’s draft team to a right-handed plow and proceeded to plow around the field

left-handed

. The Kid took an immediate liking to Folliard and decided he could make a passable gun hand out of him. With practice, Folliard got as fancy with a six-shooter as the Kid. He was very close to Billy in

personality, good-natured and fun-loving, always singing or humming a song to himself.

Tom Folliard.

Robert G. McCubbin Collection

University of Texas at El Paso Library, Special Collections Department

“He was the Kid’s inseparable companion,” recalled Frank Coe, “and always went along and held his horses. He held his horses when the Kid would pay his attentions to some Mexican girl. It mattered not whether he was gone thirty minutes or half the night, Tom was there when he came out.”

Charlie Bowdre had a ranch on the Ruidoso not far from the Coes and Doc Scurlock, another prominent Regulator. He was born in Georgia, but he had been raised in DeSoto County, Mississippi, the son of a wealthy plantation owner. Bowdre had been in trouble with the law well before the Lincoln County War. One of his worst episodes occurred in August 1877, when he and two companions terrorized

the town of Lincoln in a drunken rampage. One resident referred to Bowdre as a “would be desperado.” On the other hand, George Coe thought that Bowdre and Bonney were the Regulators’ best fighters.

Charlie and Manuela Bowdre, 1880.

“They were both cool and cautious,” Coe recalled, “and did not know what fear was.”

Bowdre was eleven years older than Billy and had another distinction: he was the best dressed of the lot, having a fondness for fancy vests.

The fourteen months since the Big Killing in Lincoln had been mostly hell for the Kid and his compadres. On August 5, 1878, Billy, Folliard, and Bowdre, along with seventeen other Regulators, swooped down on the Mescalero Apache Indian Agency. Their sole purpose was to steal a few of the Indians’ horses. When someone saw what they were doing and the shooting broke out, agency clerk Morris Bernstein was killed. Even though Billy did not have anything to do with ending the clerk’s life, he was one of four men indicted for Bernstein’s murder. George Coe had also been indicted for the killing, and later that same month, he and cousin Frank decided it was time to get away from Lincoln County. Billy pleaded with the Coes to stay, but the cousins were tired of living like outlaws, and they wanted out.

“Well, boys, you may all do exactly as you please,” the Kid told them. “As for me, I propose to stay right here in this country, steal myself a living, and plant every one of the mob who murdered Tunstall if they don’t get the drop on me first.”

In September 1878, after numerous complaints from the Territory’s citizens, and a highly critical report from a Department of Justice special investigator, Governor Samuel B. Axtell was finally removed from office. He was replaced by Major General Lew Wallace, an aspiring novelist who had been a member of the military commission that tried the conspirators in President Lincoln’s assassination. In November, Governor Wallace granted amnesty for those who participated in the Lincoln County War. Unfortunately, this amnesty did not

include any who had already been indicted on criminal charges, and that included Billy and some other Regulators. But Wallace was no friend of the Dolan crowd, either, and he quickly decided that Gold Lace Dudley was one of Lincoln County’s biggest problems.

In mid-February 1879, Billy tried to make peace with Jesse Evans and the rest of the Dolan faction, and the two sides met in Lincoln on the eighteenth. Billy brought along Folliard, Doc Scurlock, George Bowers, and José Salazar. Facing them were Jesse Evans, Jimmy Dolan, Billy Mathews, Edgar Waltz, and Billy Campbell. After a tense and shaky start, the two sides came up with several conditions for a truce—one of them being that neither side would testify against the other in court. The penalty for breaking any of the conditions was death. Once everything was settled and agreed upon, the drinking commenced. About 10:00

P.M

., the men spilled out onto Lincoln’s main street, singing and shooting their guns into the air. It was then that lawyer Huston I. Chapman, who had just arrived from Las Vegas, made the mistake of thinking he could walk through the rowdy bunch. The one-armed Chapman had been hired by Susan McSween to bring Dudley to justice for his role in the killing of her husband, which made Chapman an enemy of the Dolan crowd.

A drunken Billy Campbell accosted Chapman and asked where he was going. Chapman, his face bandaged due to an attack of neuralgia, told the boys to mind their own affairs. It was the wrong answer; Campbell ordered the lawyer to talk differently—or else.

“You cannot scare me, boys,” the feisty Chapman said while lifting a bandage from his face to get a better look at the ruffians. “I know you and it’s no use. You have tried that before.”

“Then,” Campbell replied, “I’ll settle you.”

And with that, Campbell fired his pistol into Chapman’s breast. As the attorney fell, Jimmy Dolan decided that he would double the deed, aimed his Winchester and fired a round into the poor man’s body. As Chapman’s clothing smoldered from a small fire ignited by the pistol’s

powder flash, a joyous Campbell let slip that he had promised Dudley he would kill the troublesome attorney. The Kid and the others did not know what to do. John Henry Tunstall had been shot down exactly one year earlier, and ever since that horrible day, many people in Lincoln County had been killed, and now another man was dead.

Chapman’s murder outraged Wallace, who realized that he had to take serious action. In early March 1879, the governor traveled to Lincoln and got Dudley removed from command at Fort Stanton. He then set about going after Chapman’s murderers, and he believed the guilty parties included the Kid and Folliard, as well as Dolan and his cronies. During these efforts, the governor received a curious letter from W. H. Bonney:

Dear Sir: I have heard that You will give one thousand $ dollars for my body which as I can understand it means alive as a Witness. I know it is as a witness against those that Murdered Mr. Chapman. if it was so that I could appear at Court I could give the desired information, but I have indictments against me for things that happened in the late Lincoln County War and am afraid to give up because my Enemies would Kill me…. I was present When Mr. Chapman was Murdered and know who did it and if it were not for those indictments I would have made it clear before now…. I have no Wish to fight any more indeed I have not raised an arm since Your proclamation. as to my Character I refer to any of the Citizens, for the majority of them are my Friends and have been helping me all they could. I am called Kid Antrim but Antrim is my stepfathers name.

Bonney’s letter led to a secret meeting between him and the governor, and the Kid agreed to testify before the grand jury about Chapman’s murder in exchange for a full pardon. The Kid’s cooperation was no easy thing because he knew that Dolan and Jesse Evans, both

indicted for Chapman’s murder, would be anxious to put a bullet in his back. Wallace had no such risk. On the contrary, there was the good possibility that the Territory’s newspapers would laud the governor for prosecuting Chapman’s killers. Unfortunately for both the Kid and the governor, it did not work out that way. As Governor Wallace famously wrote some time later, “Every calculation based on experience elsewhere fails in New Mexico.”

Billy held up his part of the bargain. He testified openly at both the grand jury proceedings and the subsequent military court of inquiry for Gold Lace Dudley (Dudley was exonerated of any wrongdoing). But he never got the pardon the governor promised, and District Attorney William Rynerson made it clear that he was not going along with any deal the governor made.

“He is bent on going after the Kid,” Wallace’s confidant, Ira Leonard, wrote the governor on April 20. “He proposes to destroy his evidence and influence and is bent on pushing him to the wall.” Fed up with waiting on Wallace to make good on his pledge, the Kid and Folliard, who had also submitted to arrest, quietly slipped out of town on June 17 and headed for Fort Sumner. Billy’s chance to go straight—if such a thing was truly possible—was gone.