Time Bandit (16 page)

Authors: Andy Hillstrand

Neal with Bandit

Johnathan’s “cooler” Harley

Johnathan with two monster crabs

Johnathan’s Harley burning rubber

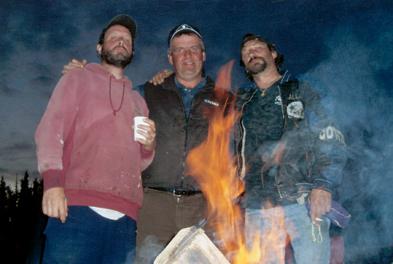

Fish camp around the oil-drum fire. Russ, Dino, and Johnathan

Taking aim: Johnathan, 2007

Fishing Fever

, Johnathan’s salmon boat, on the grid

Andy with Cali and Bait

Andy (right) with Dad

Magnetic darts at fish camp set where we would fish

I hit the switch in the wheelhouse for the warning sirens, and all hands ran to their stations. We followed the smoke belowdecks. I threw on a re-breather and without triggering it, I aimed an extinguisher at the “flame,” which I soon “put out.” The Coasties stood by, watching us scurry around in utter seriousness. We did not go through the drills exactly as prescribed. We used common sense that often gets left out of the written regulations. The Coasties debriefed us. They wanted to know what we could have done better. And we talked about it. They brought up other scenarios, like a hole in the boat, abandon ship, flooding, a Mayday, the whole drill. We must have passed muster, because they then proceeded to the next tests with survival suits and deployment of our ten-man raft.

Getting into a survival suit is no mean feat even for someone agile, trim, and calm. But panic can scramble brains. The survival suit is the first line of defense on the Bering Sea. The crewmen keep them within an arm’s reach when they are sleeping. When the alarms ring and either Andy or I order the crew into their suits, they have sixty seconds to shake out the bag, lay the suit out on the floor, sit down, push their legs in, stand up, push their arms in, pull up the long lariat on the zipper, put the hood over their heads, and close the Velcro flap over their mouths. It is a struggle but beats the alternative.

We waddled to the rail. I had assigned Russell the life raft duties. He jettisoned a hard plastic chamber that was bolted to the top of the wheelhouse on the aft deck. The raft deployed automatically when it hit the water. As usual, the Coasties asked us to follow the raft in. That always gives me pause. The water is so feared by us, even a trial run triggers a feeling of dread. In our minds, Bering Sea water equals death. We balk even when we know that the dock is only feet away.

We took our positions on the rail, crossed one forearm over our faces with our palm over our mouths, and jumped. Once the water closed around me, even though this was Dutch Harbor, I imagined myself in a real crisis. The exercise took hold of me with a seriousness that surprised me. One by one, we swam to the raft and struggled in on our stomachs until the Coasties told us to come back onboard

Time Bandit.

Once the Coast Guard was finished with us, we were not done. Next, we were visited by the state government in the presence of Fish & Game and the federal government in the guise of National Marine Fisheries Service, which itself is part of NOAA. Once, OSHA boarded us with the unwanted news that we were using the wrong kind of welding gear. Sometimes these agency representatives can be adversarial, but most of the time they are trying to help. Andy and I have wondered if the space shuttle has this much oversight.

In the end, I doubt that crab fishing could be made safer than what it already is and still remain efficient and cost effective.

Time Bandit

is eminently stable, as I have said. We carry fewer pots than we are allowed. We use the latest firefighting equipment. We take extra precautions with the crew. We train. We treat fishing on the Bering Sea as the serious, unforgiving task that it is.

Now, two chores remained before we could leave Dutch to begin our season in the fall of 2006. We wanted to be out on the king crab grounds in the southeast Bering Sea near the Bristol Bay line before the season officially opened. For an irrational reason that has to do with our competitive natures, we wanted to be the first to drop pots on the opening hour of crab season, even though with our IFQs, the date hardly mattered. Last season we knew what we would catch. But we worried about making our delivery dates with the processors. If we missed our appointment by only a couple of hours, we would have had to go to the back of the line, risking the loss of the crabs in our holds. Sometimes the wait can be days.

Neal and I led the way from the dock in our rented SUV. He had lists. I had only preferences. Driving over to Dutch’s Eagle Quality Center in snow flurries, I noticed an unusual number of bald eagles soaring over the canneries and the hillside that runs down to the harbor. Eagles are as numerous on Dutch as pigeons in a park; they are glorious and beautiful to watch as they swoop over the road. We drove through puddles and ruts in the gravel road that leads away from the canneries toward the commercial section of the harbor. Everything on Dutch wears the cold gray coat of winter, from the sky to the land. This is not a pretty island. Like

Time Bandit,

its purpose is work.

Neal and I each wheeled a shopping cart into Eagle’s, which looks like a warehouse with high ceilings of structural braces and conduits for heat and ventilation. The rows of grocery shelves are spaced to allow fishermen to wheel large platform dollies for their groceries. I doubt if anyone comes here for only a quart of milk.