Time Bandit (14 page)

Authors: Andy Hillstrand

Matt grabbed the first crewman and took him into tow. A man-sized metal basket was lowered from the helicopter. Matt worked to get him into the basket in seas that continually flipped the man out. He was not helping his own cause. He was rigid and his right arm was stiff, and Matt had to bend him to get him into the basket. The first crewman was finally hoisted up. By the time Matt turned around to reach for the next crewman, the wind had blown the raft away, and without explanation, the helicopter left—just disappeared. Matt treaded water alone for the next fifteen minutes, wondering what was going on. He told me he thought in back of his head, “I got three more guys to rescue and I’m pretty winded. I have no helicopter and I don’t know what to do.”

The Jayhawk finally did return and hovered. Matt used a strop to hoist the second man, then rode the cable up to the Jayhawk to warm up. That helped. And he went back down into the sea for the last two. The third crewman was hard to reach. The raft continued to move with the wind. The Jayhawk hoist operator and cockpit crew had put Matt down broadside to the raft. He had to sprint for two minutes in the water to reach the raft only a few feet away. It would have stayed beyond his reach if a swell had not surfed him to it. Water had leaked into the captain’s survival suit. He was heavy to start with. Matt was afraid that the additional weight of the water in the survival suit would tug the captain out of the sling. He told him to relax and let the hoist operator do the work. Matt said the man had a look in his eyes that said, “I’m not going to make it.” The hoist line took the load. He was winched to safety. The last survivor, by comparison, was easier.

The four rescued men off the

Hunter

were hypothermic, two seriously so. They were out of the water and in danger of drowning but not yet out of danger. It was Matt who told me the horror of serious triage performed in huge waves of icy 36-degree water. If he is faced with several bodies in the water, and his resources to save all of them are few, he has to make hard choices. He said the specter of this happening keeps him awake at night. In only seconds he must evaluate and prioritize consciousness, breathing, and circulation. He has to ask himself who is the most salvageable. I could never do that, and neither could most people I know. It would be playing God.

Matt has dealt with some hard cases. One time he was lowered to the deck of a boat to rescue a fisherman whose body was caught on a steel winch drum. The initial report indicated that the man was already dead. Matt was going to pick up the body. But when his feet touched the boat’s deck, the man looked at him with knowing eyes. He was still alert and trying to tell him something but noise of the helicopter drowned out his words. The man gave him a look that said, “I’m not done yet.” He was lashed to the drum by tight strands of two-inch braided nylon rope, which was connected to a supply boat they had been towing. The rope had broken both the man’s lower legs and femur bones and his pelvis, and part of his scalp was peeled off. Miraculously, he survived.

The same thing nearly happened to Andy one time when he and I were out alone on my boat,

Arctic Nomad,

long-lining for halibut in the Cachemak Inlet near Homer. A current was running about five knots, and the line, as a result, kept popping out of the gerdie, a hydraulically driven drum on which the long lines wrap themselves as they are brought in, hopefully heavy with hooked halibut. The line had wrapped around Andy. I quickly pulled the boat out of gear. The line was squeezing him and would have cut him in half or pulled him overboard and drowned him. Or he would have lost both arms. Andy was screaming, “Cut the line, cut the line!” I whipped my knife out of the scabbard and ran to the back deck from the wheelhouse. I was not thinking where to cut the line. I was close to panic. If I had cut the line behind my brother he might not have come out alive. We laughed so hard with relief we were crying.

Like anyone who works on the sea, Matt is constantly surprised by human endurance and the will to survive. He deals all the time with people on the edge in extreme circumstances. Some people just give up, but mostly, he said, they fight. One man he went to rescue on the Bering Sea had caught his arm in a winch. The bone was broken, the muscles were strung out, and the pain was excruciating. The man was eerily calm, sitting on the deck holding his arm and smoking a cigarette, waiting for the helicopter to arrive. At the same time, others who are barely in any danger freak out. He reflected on serendipity, the chance of the sea. He shook his head.

I thought about the F/V

St. Patrick,

December 2, 1981. She was a 158-foot scallop boat with a crew of eleven that ran into a storm at night five miles west of Marmot Island, near Kodiak. She took on water in her engine compartment and listed 90 degrees, balanced on the edge of going over. The crew put on survival suits, tied themselves together, and abandoned ship; the life raft was lost. The crew, fearing that the boat would turn over on them, swam as far away as they could before exhaustion overcame them. The current and the winds did the rest. Eight crewmen and one woman drowned or died of hypothermia that day and the next. Two survived. The agony of the

St. Patrick

was that she had righted herself after the crew had abandoned ship; a Coast Guard cutter towed her into port. They would all be alive if only they had stayed with her.

The same was true twenty years ago of a scow that was sinking off Kodiak in a bad storm. The crew of six had five survival suits. The cook lost out. The crewmen jumped overboard, and the cook opened a bottle of liquor and got drunk at the galley table. He passed out, and when he woke up the storm had gone past, and he was alive. The crewmen who had jumped overboard died of hypothermia.

Another of Matt’s surprises, he told me, is the size and invisibility of a man in the sea. He said a human head in the water is no larger than a floating basketball. “You can miss people,” he told me, with the search helicopter flying at 200 feet and 80 knots. “You can miss them so easily it makes you want to cry.”

That is the best part of the Coast Guard. The worst is their watchdog powers over

Time Bandit,

its safety gear, and our training to react in a crisis. I tend to think the Coast Guard has it out for me for what I did once on a day that was blowing 50 in the harbor, and

Time Bandit

lost steering as we were coming in. I called the Coast Guard to tell them I had no steering, and I put bumpers and buoys over the side. But we slammed the Coast Guard’s big cutter

Roanoke Island

anyway. The officers in charge could not see this merely as an accident. They thought I was drunk and gave

Time Bandit

’s crew and me drug tests.

I can usually talk to anyone. And Andy can talk to horses. He reads people like he reads his horses. So I leave the Coast Guard inspections for him to handle. Sometimes, I see a twenty-year-old Coastie come on

Time Bandit

who wants only to rip me a new one. I get out of the way. They come onboard and get up our butts like rubber coconuts. They tell us we cannot leave port until we get this fixed or that fixed or this or that done. We have too many pots on deck. Andy gets out the calculator, and not only do we not have too many, we have too few. The Coastie starts arguing over pot size and weight.

When they boarded us last year, three Coasties asked for our crew’s licenses, which they inspected and noted on their clipboards. They checked

Time Bandit

’s papers. They counted extinguishers and flares, the Satellite 406 EPRIBs, life rings, life rafts, and the integrity and check-by dates of our survival suits. They looked carefully at our stability letter, which states how many pots we can safely carry on deck. Intentional or not, miscalculations (inputting the wrong pot weights) have in the past caused ships to capsize and now pot weight is monitored to the pound. The Coasties behaved in a formal, professional manner. Then, before they went away, they detonated a smoke bomb in our engine room and shouted “Fire!”

Photo Insert

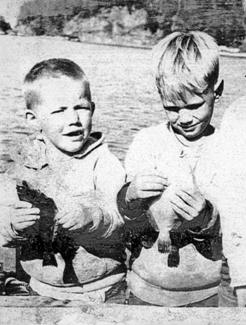

Getting into trouble: Johnathan (left) and Andy, four and three years old

Johnathan’s (left, age four) and Andy’s (age three) first flounders

Try Again

, our childhood “pirate boat”

Grandma Jo Shupert, 1945

Ice fishing on the Bering Sea, 2006