This Is Gonna Hurt: Music, Photography and Life Through the Distorted Lens of Nikki Sixx (2 page)

Read This Is Gonna Hurt: Music, Photography and Life Through the Distorted Lens of Nikki Sixx Online

Authors: Nikki Sixx

Tags: #Psychopathology, #Biography., #Psychology, #Travel, #Nikki, #sears, #Rock musicians, #Music, #Photography, #Rock music, #Rock musicians - United States, #Composers & Musicians, #Pictorial works, #Rock music - United States, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Personal Memoirs, #Artistic, #Rock, #Sixx, #Addiction, #Genres & Styles, #Art, #Popular Culture, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography

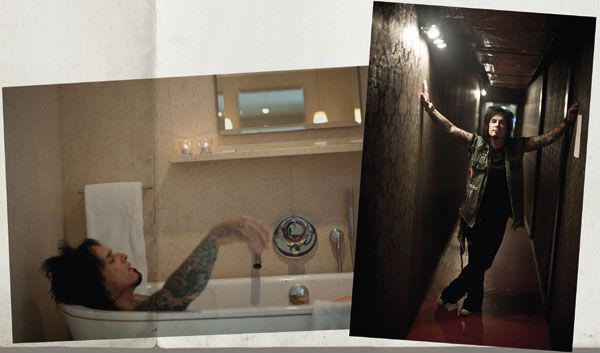

Life is full of so many false starts and abrupt finishes and unexpected detours. Just when you think you have it all figured out, something new comes along and rips the rug out from under you. I cherish this about my existence. People come up to me and ask, “Nikki, how can you be in one of the world’s biggest rock bands, have a side band with a hit album, have a clothing line, be a successful author, have your own radio show, be a father of four, and on top of that still have such cool-ass hair?” I say, “Wait, what about my photography?”

By now, I can’t imagine not taking pictures whenever the moment moves me—from the first rays of morning light bouncing off the windowsill to the laughter roaring out of a wild man standing on the corner of the freeway, begging for change. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, they say, and I say they’re right. I also say you see what you want to see, so I keep my eyes wide open at all times.

I sometimes feel like a robot, scanning the planet for information. The conversation I have with a fan in an airport,

DOWNLOADED

into my brain. The kid who runs in front of my car chasing a ball, making me stop on a dime,

DOWNLOADED

. The woman at the gas station driving a Rolls-Royce and yelling at the attendant that he didn’t properly clean her windshield,

DOWNLOADED

. As an artist, I take it all in knowing it will somehow be regurgitated later, maybe as a lyric, or a chapter in a book, or a photograph.

When I see something, I grab whatever’s handy and start clicking—my iPhone, my Holga or Diana toy cameras, my little Canon point-and-shoot, my homemade pinhole wooden camera, or the big Nikon D3, or my new friend, a Gilles-Faller wet-plate camera from 1890. All just different ways to collect what falls beneath my gaze.

I think the photographer who turns up his nose at a low-res cell-phone camera has lost what he fell in love with in the first place: capturing that magical moment. Taking a picture is just telling a story. You know, like the blink of an eye, a flash, then it’s gone. I know that for me, the magic is in the moment. I live for the mystery of that. I learned this somewhere along the way. I hear it in AA meetings often: one day at a time. I even hear one minute at a time.

I forget this sometimes, and when I do I start to feel out of sync with life. I think photography realigns me with the moment.

I don’t have a favorite style of photography. I love the same greats that every fan does, like Joel-Peter Witkin and Diane Arbus. But there are so many others. I recently found a wonderful book when I was in London, titled

Le Temple Aux Miroirs

by the French photographer Irina Ionesco. She turned the world on its head in the 1970s when she took photos featuring her underage daughter in tantalizing positions, a presexual kitten mixed with bordello queen. Raw and beautiful in the lighting and rich in texture thanks to the darkroom work, it is brilliant. But it is also her own young daughter, nude for all the world to see. It makes me think, as an artist and a parent. One side of my brain is inspired, one side repulsed.

Old cameras capturing odd people with ancient souls, sitting on antique books and furniture, sometimes shot in abandoned places, or sets made to look suitably destroyed and decayed…everything and everybody here on this polluted blue marble is destined to leave a mark, and this is one of mine. I will leave it to the history books to decide whether it’s good or bad. If it’s up to the critics, well, put it like this: word on the street is there ain’t no Grammy in my future. I ruffled way too many feathers in the old boys’ network for that to happen. I hope to follow suit in photography.

Photo sessions for me are like injections of life. I pace back and forth impatiently, like a man with a machine gun, and trust me when I say I have an itchy trigger finger. Once I get the picture, I “get the talent out,” as the expression goes, meaning I send the models away. This is the moment when the magic comes to life. It’s like capturing a soul. Going through the photos frame by frame, cursing the focus of this one, amazed at the perfection of that one.

Then it’s all about the processing of the images, the dodging and burning, and if there is any juice left in your engine (or time on the clock) maybe a print or two to hold in your hands. I almost always take an image home with me at the end of a shoot, like a cannibal takes a head. A trophy, I guess.

My favorite sessions are with the old, decrepit, deranged, and uniquely beautiful. The once living or now on the verge of dying. Maybe we’re just stopping time until we graduate to the next level (some call it heaven). No matter how they look, I say they are pretty things. After all, if they can make you feel, they must be special. There is a sensation to something that has been around for a long time, a kind of energy that I get from it. The older we are, the better we become. Just look at Keith Richards. (I am not far behind.)

I search high and low to find people who move me emotionally to photograph. Some come to me through friends of friends, casting directors or other photographers, but it isn’t easy. I have tried my hardest to get into places most people run from. Shooting galleries are almost impossible to penetrate, and mental institutions have so much red tape you’d think they were sacred. Whorehouses aren’t easy to get into when you’re lugging a camera, but I have gotten into a few.

For me, it’s love of personal contact that pushes my creativity. That’s why I love shooting on the street. Whether it was in Cambodia, Thailand, Australia, or someplace else, finding people who have fallen on the hardest of times, those who seem forgotten, has provided me with my happiest times as a photographer. They need to have their beauty acknowledged by capturing the image.

I always take my cameras with me on tour. Photography takes me away from the normal routine (and boredom) of airport-limo-hotel-venue. Sometimes it takes me far, far away.

In Vancouver, I was talking to the concierge at the hotel where Mötley Crüe was staying. You’re supposed to ask the concierge when you’re searching for the nearest great restaurant or local hot spot. Somehow I always feel like an alien because I never want to know about the nightlife (at least not that kind). But I knew that some questions are better whispered than announced to the whole lobby.

I looked down at her name tag and asked the question under my breath—way under my breath, so far under my breath I may have seemed like a crazy person miming. I said,

“Julie, I’m trying to find the most drug-infested part of town.”

She said, “Of course, sir, I’ll get my manager to help you.”

The next name tag in front of me belonged to Karl. “May I help you, sir?” he asked. By the way he blurted it out, I could tell Julie hadn’t filled him in on my request. I repeated it, at which point Karl took me aside and asked a few questions, mostly to cover the hotel’s ass, I think. When you look like I do and ask where the crack houses are, people might assume incorrectly about what you’re after. Once I explained, he said he had a few friends who are photographers and so he knew the perfect place, but first I needed to understand how dangerous it was. Imagine my smile when I got what I asked for.

Jumping into a van with a bag of cameras and six hundred Canadian dollars in my pocket was my idea of a perfect day off from the crazy traveling circus. Running up behind me came my 350-pound (and equally bighearted) security guard, Kimo. I told him he had to stay at the hotel because he would scare people away. We had a heated argument, during which the tour manager and then actual managers were called. Finally, to save time, I just caved in. We all agreed that Kimo could come—as long as he stayed far enough away so nobody would notice him, but close enough to save me if necessary. Frustrating sometimes to be thought of as a commodity.

Sucking up my ego and picking up my cameras, I was off to the crack district. It took ten minutes to get there from our five-star hotel, and three hours to get Kimo to allow me to enter the most dangerous alley in Vancouver. It wasn’t unlike a million other alleys I’ve seen except it looked bottomless. I couldn’t even tell if it was a dead end or not. Brick buildings lined it, old banks and government offices, now abandoned. This isn’t prime real estate unless you’re a junkie.

I sat alone at the mouth of that alley for over an hour until one guy came up and asked what I wanted. I told him I wanted to take pictures. I wanted to be a fly on the wall, so to speak. I told him I was an ex-addict and maybe some of these pictures would help other people who were thinking about doing drugs.

His response was simple: “How much?”

Now, being one to bait the hook with the fattest worm, I gave him fifty dollars and he took off to tell the others that I had money and was one of them. Before long I was twenty feet into the alley and a hundred dollars lighter. I saw Kimo pacing back and forth as I handed out cash and disappeared deeper and deeper until finally I was out of his sight altogether. At last.

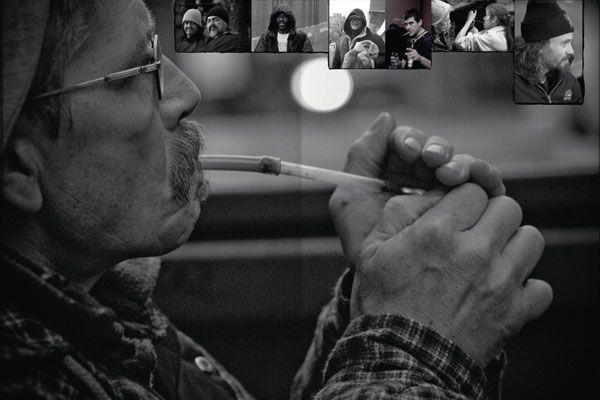

The alley smelled like dank piss and rotting garbage. Plastic tarps strung from one garbage bin to another created shelter from the rain and added to the stink. At first it looked like ten, maybe twelve people in clusters, but as I went deeper I saw more groups, maybe trying to keep warm and definitely trying to get high together. It was like a community from hell. There were no young kids that I saw. I don’t think I could have handled that. I saw enough of that on a trip to Cambodia and that is another level of heartache.

VANCOUVER HOMELESS

fig.vc9

By Sixx:A.M.

She was born at 6am on New Year’s Day

In an alley right at the heart of where

homeless children play

And the truth is we will never even know her name

Cuz as long as we can fill our glasses up

we will look the other way

EYE OF THE NEEDLE

fig.vc78

My interaction was minimal. Nobody knew who I was, and if they did, why would they care?

Still, I was treated with more respect and given more polite “thank yous” and “excuse me, Nikkis” than I get in some of the nicest neighborhoods in the world. They wanted to know about my addiction and recovery. They told me their dreams and downfalls. I took two hundred pictures that day, two hundred moments of hope. As I was leaving one guy asked me if I would come back and say hello someday.

I remember getting into the van and telling Kimo that people are amazing—all they want is to be accepted. Kimo looked at me and said, “Dog, you always find the good in everything. I always learn something on these photography missions with you.” It was quiet in the van riding back to the hotel. A feeling of gratitude falls over you after a day like that. Next time I’m in Vancouver, I plan on going back there. I hope I don’t recognize a single face.

Another model search started in St. Petersburg, Russia. I tried explaining to our translator, Andrei, what I wanted to shoot. First word I said was, “Prostitute.” He looked at me sadly and said in very broken English, “You are want me find girl for you today?” I said “Nyet, not girl…

girls.

” I explained how I had once rented a whole brothel in Thailand just to make some photographs. Andrei still looked confused but said, “I will see if I can find girls to take pictures of…”