This Great Struggle (30 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

IUKA, CORINTH, AND THE HATCHIE RIVER

While Lee had ventured briefly into Maryland and Bragg and Kirby Smith had made their separate and poorly coordinated thrusts into Kentucky, a third simultaneous Confederate offensive had sputtered to an abortive start in northern Mississippi. Bragg had left Price there to watch the Federals at Corinth, Memphis, and other garrisons and had left Van Dorn in the central part of the state to watch the Union threat to Vicksburg. By late summer falling water levels in the Mississippi River had driven Farragut’s ships back down to New Orleans, relieving the pressure on Vicksburg and freeing Van Dorn to join Price in an offensive that would support Bragg’s efforts in Middle Tennessee and Kentucky. Together they would have about thirty-two thousand men and could pose a severe threat to Union forces in northern Mississippi and West Tennessee, who were already detaching troops to reinforce Buell.

Unfortunately for the Rebel cause, the Confederate command situation in Mississippi was as confused as it was in Kentucky. Just as Bragg outranked Kirby Smith but could not demand his obedience until their forces joined, so Van Dorn outranked Price but was similarly hamstrung by lack of authority to command him. Price proved as headstrong and uncooperative as Kirby Smith was proving at the same time in Kentucky. The Missourian wanted to drive northeastward toward Nashville. Van Dorn thought they should attack northwestward instead toward Memphis, and valuable time passed while letters went back and forth between them arguing the merits of their rival plans.

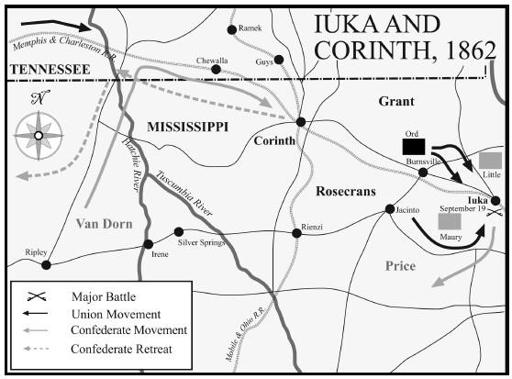

As Price maneuvered on his own, he reached the town of Iuka, less than ten miles from the Tennessee River in the northeastern corner of the state. Ulysses Grant, whom Halleck had left in command of the scattered Union forces in West Tennessee and northern Mississippi, had been following reports of Price’s movements and believed he had a chance to trap the Missouri general at Iuka. Concentrating all the force he could spare from the many garrisons Halleck had required him to hold, Grant made plans to attack. William S. Rosecrans, who was then serving under Grant, told Grant that he knew the roads in that region and that it would be possible for him to lead an independent column to strike Price from behind at Iuka while Grant attacked with his main force in front. It was almost impossible to coordinate such widely separated movements in the Civil War, but Rosecrans assured Grant it would work, and Grant reluctantly agreed. Rosecrans moved slowly and took the wrong road, leaving Price an escape route. When on September 19 Price detected Rosecrans’s approach and attacked him, another of those strange acoustic shadows prevented Grant and those around him from hearing the sound of the guns and joining the battle from the other side. In the end, Price escaped.

Chastened by this close call, Price joined Van Dorn, and the two of them agreed to attack the Union garrison at Corinth. Hoping to deceive Grant about his intended target, Van Dorn marched his army as if to bypass Corinth and move into West Tennessee, then turned back to attack Corinth from the northwest on October 3. Grant was not fooled and had Rosecrans in place at Corinth, strongly reinforced, and with more Union troops on the way from Grant’s other outposts. During the two-day battle, Rosecrans handled the defense poorly, and his troops suffered for it. Then when the Confederates nearly broke through his lines, Rosecrans panicked, galloping this way and that, cursing his men, declaring the battle lost, and ordering the burning of his supply wagons. Fortunately, the men in charge of his supply train were made of sterner stuff and ignored his order, while his frontline troops, many of them veterans of Fort Donelson and Shiloh, rallied and drove the Rebels back.

Grant had given Rosecrans strict orders to pursue the Confederates aggressively when they retreated from Corinth. Van Dorn’s indirect approach to the town made him vulnerable to being trapped, and Grant intended to do it. He not only reinforced Rosecrans but also dispatched another column to cut off Van Dorn’s crossing of the Hatchie River. These troops turned back the retreating Confederates on October 5, leaving Van Dorn at the mercy of Rosecrans’s victorious army. But Rosecrans did not pursue. Only after Van Dorn had had time to find an alternate crossing of the Hatchie and get his battered army to safety did Rosecrans show any interest in following him. By then the opportunity was past. Van Dorn was in a strong position with a secure supply line, and any “pursuit” would have meant launching an entirely new campaign, something Grant was eager to do but for which he knew his army needed further preparations. He ordered Rosecrans to halt, and Rosecrans responded by complaining that Grant had prevented him from pursuing the defeated Van Dorn.

LINCOLN TRIES NEW GENERALS

The fall elections that year saw the Democrats make significant gains in Congress and elsewhere. The newly elected, Democratic-dominated Indiana legislature was so hostile to the war effort that it might have halted the state’s participation or perhaps even considered secession. The doughty Republican governor Oliver P. Morton was equal to the crisis. He directed the Republican legislators to stay away from Indianapolis, denying the legislature a quorum and preventing it from transacting business. Then he ran Indiana without it, financing the state government with loans from the federal government and even from patriotic private citizens.

Democrats claimed that their gains in Congress as well as in various state legislatures represented a popular repudiation of the Emancipation Proclamation. No doubt there were some voters who had gone Republican in 1860 and shifted their votes two years later because of their opposition to Lincoln’s announced intention of freeing southern slaves. This was especially significant in a state like Indiana, whose southern counties included large numbers of people who had moved into the state from Kentucky and still harbored slave-state sensibilities. However, the Republican losses in Congress were actually less than was usually lost in midterm elections of that era by the party possessing the White House. In that sense, they represented politics as usual, even in the midst of a great war, and a reasonably steady though by no means overwhelming degree of support for Lincoln and his war measures, including emancipation.

And if some Americans were not entirely satisfied with every measure Lincoln had taken in trying to win the war, Lincoln was foremost among them this fall. For the past fifteen months, since the summer of 1861, he had been placing his reliance on the most professional of professional officers to lead the nation’s armies—McClellan, the rising star of the prewar army in the East; Buell, McClellan’s proteégeé and less charismatic alter ego west of the Appalachians; and “Old Brains” Halleck, as his soldiers called him behind his back, author of books on the art of war, first in the Mississippi Valley and then in overall command in Washington. The results had been disappointing, to say the least.

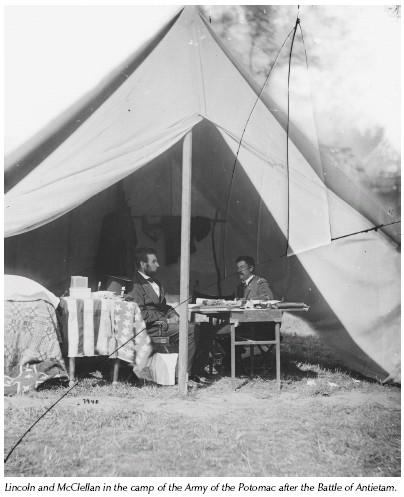

McClellan had, in Lincoln’s homely phrase, “the slows,” and his operations had been so halting as to awaken in the minds of some serious people the suspicion that he was in fact a traitor who was trying to allow Rebel victory. After Antietam he had kept his army inert for weeks, doing nothing, while Lee’s cavalry commander, Jeb Stuart, led the Rebel horsemen on a ride all the way around the Army of the Potomac. It was the second time he had done that since McClellan had been in command. When McClellan responded to one of Lincoln’s many prods with the excuse that his army could not march at present because its horses were tired, an exasperated president replied, “Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam

that fatigues any

thing?”

Finally, with painful slowness, McClellan began to advance into the Virginia Piedmont. His position forced Lee to try to cover both the Shenandoah Valley and the shortest route to Richmond—opposite directions from where McClellan was. By edging toward Richmond, McClellan was able to gain an advantageous position from which he had a shorter route to Richmond than Lee did. In the hands of an aggressive general, that position could have been Lee’s undoing, but McClellan dawdled until Lee was able to recover and regain a position between him and Richmond. That was enough for Lincoln. On November 5 he relieved McClellan of command of the Army of the Potomac, replacing him with Ambrose Burnside. To Lincoln, Burnside’s repeated insistence that he was not capable of commanding the army seemed like refreshing humility after McClellan’s unwarranted boastfulness. Burnside had enjoyed success down the coast occupying places the navy had conquered, and he seemed like the sort of straightforward general who would fight instead of always dallying like McClellan.

By that time Lincoln had already run out of patience with Buell. After Buell had tamely allowed Bragg to retreat unhindered and unpursued from his foray into Kentucky that fall, Lincoln relieved Buell from command of the Army of the Ohio on October 24. To replace him he tapped William S. Rosecrans, the victor of Corinth, though the soldiers who had served under him there could have given the president a different perspective if he had been able to sit down and talk with them. Rosecrans had enjoyed a measure of success under McClellan in western Virginia during the opening months of the war and more recently under Grant in Mississippi. Lincoln expected him to be an energetic and aggressive commander. Elevated to command, Rosecrans promptly renamed his army the Army of the Cumberland.

Lincoln had brought Halleck to Washington in midsummer 1862 to direct all the nation’s armies, but Old Brains had proven a profound disappointment. Hesitant and afraid to give orders to generals in the field, Halleck had become, in Lincoln’s words, “little more than a first-rate clerk.” And, though Lincoln did not fully understand Halleck’s role in the matter, Old Brains had left behind him in Mississippi a situation that added to the president’s frustration. Halleck had dispersed the forces there into various garrisons so that it was hard to assemble a field army large enough to take the offensive. He had also, throughout his command in the Mississippi Valley, reprimanded and threatened to remove Grant every time that officer had exercised initiative. The Union’s best commander was thus little inclined to launch another advance and again risk Halleck’s wrath. Lincoln did not understand this, but he did sense that the Union had lost momentum in the Mississippi Valley. To regain it, he was inclined to turn away from the West Point–trained professionals who had hitherto mostly seemed to lead the Union armies to strategically correct futility. Instead he looked to a political general, John A. McClernand.