Thirty Rooms To Hide In (4 page)

Read Thirty Rooms To Hide In Online

Authors: Luke Sullivan

Tags: #recovery, #alcoholism, #Rochester Minnesota, #50s, #‘60s, #the fifties, #the sixties, #rock&roll, #rock and roll, #Minnesota rock & roll, #Minnesota rock&roll, #garage bands, #45rpms, #AA, #Alcoholics Anonymous, #family history, #doctors, #religion, #addicted doctors, #drinking problem, #Hartford Institute, #family histories, #home movies, #recovery, #Memoir, #Minnesota history, #insanity, #Thirtyroomstohidein.com, #30roomstohidein.com, #Mayo Clinic, #Rochester MN

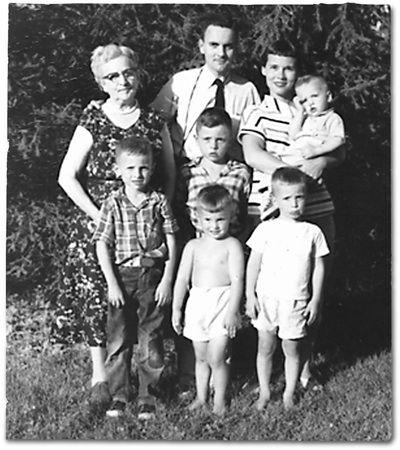

The Rock, 1960

For many years after our father’s death my brothers and I unfairly laid all the blame for Dad’s low self-esteem squarely in the frosty Puritan lap of his mother, Irene.

H.L. Mencken described Puritanism as “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, might be having a good time.” Irene rarely seemed to be having one and certainly nobody standing near her did. She was a chilly woman who banged the Bible more than she did her husband, shamed her only child at every opportunity

,

and sucked all sense of hope and joy out of every room she ever entered. Hugging her was like putting your arms around a burlap bag filled with sticks; she didn’t hug back either. Nor did she laugh. Nor ever use the word “love” that didn’t have the word “Jesus” in the same sentence.

If she’s in hell now, she’s the librarian.

She was cold like a rock and so we six boys nicknamed her “Grandma Rock.”

Her husband was a Methodist minister but none of us knew Grandpa Sullivan; he died in 1942. Later we became convinced he died early just to ditch Irene earth-side and get a head start into eternity. The six boys and Mom weren’t the only ones who didn’t like Grandma Rock; even Dad finally admitted to it, though privately. A year before he died, he confessed to his psychiatrist that while he’d at least

liked

his father, his mother was a different story.

The patient said at this juncture, “I don’t like my mother, as you can see from my scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory.” He went on to describe her as “a farm girl who taught school and married when she was 31 years old.” [Pressed for more,] he said she’s “good about church-going.”

“Good about church going”? If you were to ask any of Roger’s sons about

their

mother, we’d say: “Loving. Encouraging. Smart. Funny.” The best my dad could manage was the less-than-stellar “Good about church-going.”

(“Bob Eubanks? I’ll take Bachelorette Number 3! Because she’s ‘GOOD ABOUT CHURCH GOING!’”)

Roger’s other memories of life in Irene’s household were equally effusive: “We always had enough to eat” perhaps being his most ringing endorsement.

The patient remembers his mother as stern, rigid, and recalls guilt feelings concerning his pursuit of sexual information. He traced a history of being an only child who never felt close to his parents. Above all, the patient remembers a stern, religious environment in his childhood home. On one occasion when he was at a church summer camp, he recalls the atmosphere of the “old-time religious environment” got to him. He recalls crying and going to the altar in response to the evangelist’s plea. On the way home that night, he clearly remembers his mother’s disapproval and his feeling of resentment.

Grandma Rock offered her son a rancid little cup of her religion and when he moved to drink from it, she shamed him – “for drawing

attention

to yourself walking up to the front of the church like that.”

There are pictures of our father growing up in this religious meat locker and in all of them he looks haunted. Standing there next to his prim mother, his eyes have that same look the prisoners-of-war had at the Hanoi Hilton press conference, blinking Morse code to the photographers

. (“Am being tortured. Forced to stand next to her. Send help.”)

He’d confided to Myra that nothing he did was ever quite good enough for Irene. “If I brought home five A’s and one B, she’d say, ‘Well, what are we going to do about this subject you do so poorly in’?”

Nothing about Roger was good enough; not even the pictures he took. During one of her Rochester visits he showed Irene some slides he’d taken of his boys and in the middle of his little slide show she interrupted: “Now Roger, everybody

knows

these are your children. You should take pictures of beautiful things. Like cathedrals.”

Not only were Dad’s children not beautiful, she even took issue with the names he gave them. Kip, the oldest, was named after my father’s best friend at medical school.

But the Rock insisted, “Nobody knows whom you named him after. You should name him after somebody famous, like John Adams and such.” In a world full of sharp objects within easy reach, how this woman managed to die of just heart disease is a mystery for the ages.

Her visits to us in Minnesota were like flu season; something nasty was in the air, everybody felt vaguely shitty for a month, and when it went away we all felt better. When our

mother’s

parents drove up from Florida, we’d all wait eagerly at the end of the driveway for the arrival of their Pontiac and its big grill full of strange Florida bugs. There’d be jumping up and down, cries of “What did you bring us?” and hugs given through the car windows even before the motor was turned off. But Grandma Rock’s appearances were prissy, high-maintenance affairs heralded only by warnings from Dad about how to behave once she arrived. In a letter to her parents my mother described one such visit that happened during the last week of her pregnancy with Chris in August of 1950.

Roger’s mother came to the hospital for a few minutes to see our new baby. I knew she’d have a few derogatory things to say so I was all primed to hold my tongue. And it was good strategy. When we got to the nursery window there were five or six little pink and bald-headed babies behind the glass cuddled up in their trundle beds. Then up rolled little Christie with that full head of hair. Grandmother Sullivan’s first words on viewing her new grandson were: “Dear me. There’s not much Sullivan in

him

.” And then added in a sibilant whisper, “He looks like a

Jew!”

When my baby began waving his little arms and legs she said, “I’m afraid he’s going to be nervous like you, Myra.”

Given Roger’s childhood home, it’s not surprising that at college he recoiled at the sight of Myra’s bright homemade Florida dresses on the drab Methodist campus, or that he was vexed by the brown ink she used in her class notebooks.

(“Ink should be black.”)

In my father’s upbringing, if something wasn’t black or quiet or pious it was an affectation that “nervous” people used to call attention to themselves. Perhaps he remembered his first-and-only religious ecstasy; how it led him to the front of that Ohio church revival, and how Irene scolded him for it.

“Walking up to the front like that. Are you so special?”

Years later, whenever the six of us gathered to look at slide shows of my father’s old photographs, we played a game called “The Rock.” To win, you had to be the first to spot the old shrew lurking in the back of a photograph and shriek, “It’s the ROCK!”

For years, brother Chris was unable to even speak her name without automatically adding, “… God exercise her soul.” In fact, one winter night in the mid-‘70s, Chris was out in the unheated garage scrounging in trunks for one of his old diaries. He came back in from the Minnesota snowstorm bearing a book. He held it out to me. It was Grandma Rock’s Bible and it was cold. Very cold.

We liked the joke enough to re-freeze the Bible out on the front step for subsequent presentations to the rest of the brothers.

The Rock visits the Millstone, 1956.

I do not know if all children are born atheists, but we six were.

Watching my mother try to get us to Sunday school an observer might have thought we were vampires being dragged out into the noonday sun to fry. We made the process of getting dressed and off to Sunday services such a whiny mess that, except for our father’s funeral, few of us have any memories of sitting in a church at all. Photographic evidence, however, establishes our parents succeeded at least once. And we have Grandma Rock to thank for that.

There is a family film taken in the summer of 1959 during one of the Rock’s visits that shows the six boys wearing what appear to be Sunday School clothes. Grandma Rock was in town and Dad was putting on a show. (He never went to church, objecting even to the few times Mom took us to Sunday School. But if the Rock’s broomstick was leaning against the Millstone, you can be sure come Sunday we were all in church.)

The scene in this 8mm film begins with the entire family standing quietly at attention. We’re in front of the Millstone, behind one of the two stone benches at the entryway – we’re all silently staring at the camera. There is no laughter in the moment, no joy; it’s a police line-up in Sunday School clothes. In the back row, with pursed lips, stands the Rock.

(“It’s the ROCK!”)

In the next scene everybody’s gone and it’s just 12-year-old Kip standing there, wearing his suit and an impassive face. He holds his pose dutifully for five seconds; allowing, one guesses, for the camera to drink in the full splendor of his church raiment. He then takes a smart quarter-turn left, walks around the bench, towards the camera and off screen.

Cut to the second-born – Jeff, standing alone. It’s the same routine: the expressionless face, the sartorial photo-op, the quarter turn snap-to, the walk past the camera. And so it goes down the line even to little Collin, then barely two years old.

With the sound of the old projector keeping me company, I try to imagine what my father was hoping to capture in his camera that day; clearly, it wasn’t joy. Then I wonder if I’m so cynical I can’t accept this may simply be footage shot by a proud father of his children in a rare scrubbed-clean moment.

Maybe. But there’s a sense to the scene that Dad had barked at us just before film began to roll.

(Stand still!)

And there’s something about how he ordered us all to take those glum little marches. Hut, two, three, four.

I begin to wonder if, as a child, Dad had been ordered to make this same religious perp-walk in front of Grandma Rock’s camera. Remembering those lifeless photos of Roger as a child leads me to the bookshelf again.

The photographs in my father’s childhood album show events commonly associated with happiness – picnics, camping trips, outdoor gatherings – and yet not one person in any of the pictures is happy. The props are there: the canoe, the picnic basket, the lakeside cabin; all situations one might reasonably assume would yield at least

one

candid image of actual joy. But there sit Irene

(“It’s the ROCK!”),

the Minister, and Roger – all without expression. Perhaps this is simply the way people used to pose for photographs. But not

one

smile? Even on the outings? To make sure I’m not seeing things, I go through the album again and count the number of photos of Irene Sullivan. There are 41. She has an expression in four of them (the expression technically a smile but bears more similarity to a paper cut). In all the rest she is a totem-pole; a snow-covered gargoyle high on a church looking down on her little hell-bound congregation.

From the shelf I bring down another family heirloom, one I’ve never had the least bit of interest in – a collection of my grandfather Sullivan’s sermons. Not one of the six of us have ever read more than a page of it, peppered as it is with evangelistic clichés: “For a man may be changed and reborn in the fiery furnace of God’s wrath. … [A]ppeal against all forms of intemperance and debauchery … of the use of liquor and opium and other poisons … of immorality, adultery, of all social forms of sin, of worldly lust, impurity and perversion of nature

.”

Growing up, Roger listened to these sermons and watched as his father’s congregations nodded in rapt agreement that God was “vengeful,” God was “jealous” and that God would send you to Hell if you did not tread straight and true on “the great moral highway.”

Several pages into these nearly hundred-year-old sermons, I discover how Irene and the Minister may have divided the labor.

From Rev. Charles W. Sullivan’s sermons, 1917:

A mother could predestine a child to a religious and moral life by her high idealism when he is born … for she has him tied to her apron strings and almost perfectly under her control. He is the seed bed and if she is so determined she can plant that seed bed so thickly with religious and spiritual motives that it would almost require insanity or a moral revolution to tear up her work.

Like many households of the era, the raising of children was left to the women. Appropriately, the reverend set out to save the world’s souls leaving Irene in charge of the seed bed of Roger’s little soul, planting it “thick with religious and spiritual motives.”

The Reverend may have been the mastermind, but Irene was the axe-man.

Before I return the books to the shelf, I open the photo album again and turn to a last small picture of Roger; my father, as an eight-year-old. He too is dressed in his church clothes and sitting on a stone bench nearly identical to the one in our family film. He looks a little sad. The impression I get is he believes Jesus loves him, but his mother, he’s not so sure about.

* * *

There’s a line from Camus: “After a certain age, every man is responsible for his own face.”

Passing blame back up a generation seems to be an American pastime. When we find ourselves standing in front of the judge, we’re all suddenly victims.

“Yes, your honor, I did in fact fill those vats in my basement with body parts but I had a sad childhood and I’d like to leave please.”

Perhaps I am too hard on Irene. Her parents, Susannah P. Love and Frank Compton may have been even worse. Following this line of reasoning, the blame-storming session leads logically to a bitter old Australopithecus spreading guilt and anger around Olduvai Gorge.

“Well, Thog, that isn’t much of a bone tool, now is it?”

But my father’s monstrous behavior in his final years belongs on his bill, not Irene’s. So too, then, do his acts of goodness, as do his early years when he was a loving father. With Irene-and-her-Bible as his mother, it’s to my father’s credit he was ever as good a man as he was. According to my mother, the man she met was a sparkling, funny, passionate, and gentle man. And if none of that counted, passing the son-in-law test with a character as formidable as Myra’s father was an accomplishment worthy of a tattoo.

Roger didn’t set out in life to be a father; he set out to be a missionary doctor. But when we happened along, he found great joy in raising a family. Irene hadn’t frozen it out of him. He was capable of intense love. He also beat the odds coming out of Irene’s meat locker with his creativity intact. He became an extraordinary photographer. Roger bought a Roliflex camera, built a darkroom in the basement of the Millstone, and produced hundreds of excellent portraits of his family (some are in this book). Chris and Jeff both remember many good hours with Dad in the red light of the darkroom, gently shaking pictures to life under the developing chemical, Dektol. Kip remembers after winning a hockey game Dad carried him on his shoulders through the front door of the Millstone.

“I can clearly remember how loving Dad could be with us in his healthier days,” Kip says. “He loved tickling and kissing us almost to death, sledding with us in winter, and throwing the football around in summer. He was such an accurate passer I could have run around the Millstone yard all day long chasing his passes. I have one particularly good memory of sitting at the dining room table, getting ready to eat with all you guys. And when Dad came home, he went down the line stopping at each brother and kissing you on the cheek from behind.”

Roger was different in the early days. We all were.